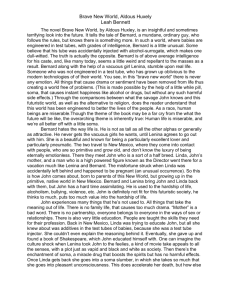

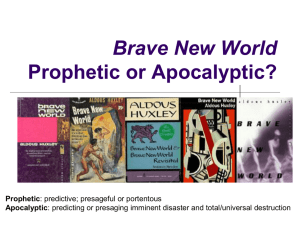

Brave New World Aldous Huxley

advertisement