How to Prevent Plagiarism and Other Acts of Academic Dishonesty

advertisement

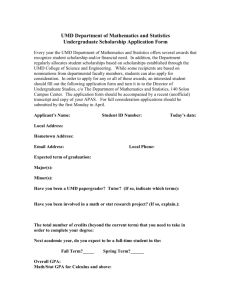

Academic Integrity: How to Prevent Plagiarism and Other Acts of Academic Dishonesty in Your English 101 Classroom 1) Include in your course policies AND your syllabus a statement on your expectations for your students regarding academic integrity and directions to the University of Maryland’s guidelines on academic integrity. Suggest requiring your students to get there via the “How do I…?” link on the library’s home page: www.lib.umd.edu. Under “cite research & create a bibliography,” students will find a section titled “Academic Integrity and Plagiarism.” Students can also get there directly by clicking on the following link: http://www.lib.umd.edu/guides/honesty.html 2) Include links to the following websites on your ELMS site, and include them as required reading on a day that you discuss Academic Integrity. (These are the “Readings on Academic Integrity” specified as being on Blackboard on the sample syllabus.) Student Honor Council Page on Academic Dishonesty: http://www.studenthonorcouncil.umd.edu/whatis.html Library Page on Plagiarism http://www.lib.umd.edu/UES/plag_stud_what.html Information about the Honor Pledge: http://www.studentconduct.umd.edu/aca/honorpledge.html 3) Try to tailor each assignment to your own specific course. You could do this by building the course around current news stories, an academic interest of yours, or a theme. For example, I used to require that my students write an encomium that Julie Dash’s 32-minute film Illusions deserves praise. Dash’s film is only available in a few select academic or research institutions, and there are very few articles about the film online. I used to tell my students that “I have read all eight.” 4) Vary your course. As each of you becomes an experienced instructor of English 101, you will discover certain assignments that work really well. The temptation is to rely on exactly the same core texts and exactly the same set of directions. Either change the core texts or include a specific but slight, mandatory change in the format or the directions. This will make it more difficult for a student to submit a paper that he or she wrote for a previous course (including English 101) or to submit a paper that a classmate had completed while taking English 101. 5) On the first or second day of class, have your students fill out the Information Sheet and/or the Writing Autobiography as a means of finding out whether your students have taken English 101 or a comparable course at UMD or elsewhere before enrolling in your course. As a follow-up question, ask those students what they wrote on before; then require all of your students to choose brand new topics. Eklund/Lawton/sce 6) Refer back to the in-class diagnostic essays that you had your students fill out on the first day of class. If there is unbelievable disparity between the writing style of the diagnostic and that of the submission, look for more concrete evidence of academic dishonesty. You could begin by google-ing a sentence or a portion of a sentence that strikes you as remarkably sophisticated. If there are technical words or vocabulary that you are not familiar with, look for a source. If you are still suspicious but cannot find evidence, ask an experienced instructor, a coordinator, or Professor Enoch. 7) If you are reviewing a rough draft, engage the student to provide a thoroughly nuanced definition of a complex term. If he or she has difficulty, ask the student if there was a source; ask to see the source; and let the student know that it is dangerous to use a source if he or she does not understand the full meaning. Add that he or she must credit the source regardless of whether he or she is directly quoting it or paraphrasing it. Point out that this act of “giving credit” must include both a parenthetical citation (invoking the author’s last name or a shortened version of the title and the page number) and a works cited listing that follows the assignment. 8) Spend multiple class days on the differences between quoting and paraphrasing. Emphasize that both acts require correct MLA citation (or whatever style-guide their field requires or their instructor requests). 9) Tell your students they will be held responsible for accurately listing the pagination of each quote or paraphrase and citing each reference appropriately. Let them know that the same expectations will exist in every class that they take at the University of Maryland, regardless of whether their instructor specifically requests a bibliography, footnotes, and/or parenthetical citation. 10) Point out the dangers of parroting the textbook definition. Point out that all sources, even students’ textbooks--such as Engagements With Rhetoric: A Path to Academic Writing--must be cited and referenced in works cited listings if quoted or paraphrased. 11) Invite another instructor of English 101 or an academic official from the Office of Student Conduct to address your class on the subject of academic integrity. Invite your students to ask the guest lecturer questions. Lastly, invite your students to follow up on any questions they may still have in class or during individual office appointments. 12) Finally, witness every step of each student’s composition process. Require that a copy of the student’s rough draft be submitted to you on each day that a rough draft workshop is held. If you return the rough drafts to the students, require them to resubmit the commented-upon versions with their final submissions. Eklund/Lawton/sce