natural unemployment and the limits of government

advertisement

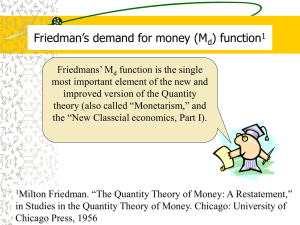

EC301 Macroeconomic Policy Dr. Derick Boyd UNIVERSITY OF EAST LONDON EAST LONDON BUSINESS SCHOOL - ECONOMICS fn. 301 Milton Friedman and the monetarists - natural' unemployment and the limits of government ECO301 MACROECONOMIC POLICY MILTON FRIEDMAN AND THE MONETARISTS: 'NATURAL' UNEMPLOYMENT AND THE LIMITS OF GOVERNMENT We began developing our understanding of the Classical economic model in the form of Say’s Law and the Irving Fisher Quantity Theory of Money Equation and their interaction. We saw that the tendency for the model to tend to equilibrium depended on ‘automatic adjustments’ brought about through the perfectly flexible adjustment in prices (notably real interest rate and real wages). Last week we examined the attack on the Classical model led by Keynes and Kalecki. We saw that the attack on the Classical model began from the late 18th century but the successful development of a theoretical argument to counter the Classical notion that the economy tended toward some form of optimal operating conditions – was not until the 1936 publication of John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. The automatic adjustment to equilibrium, a fundamental feature of the Classical model, was criticised. Keynes argued that the price mechanism in the Classical model would not always produce optimality conditions, that is: (i) real interest rates may not adjust to bring about full-employment equilibrium; and, (ii) the real wage rate may not flexibly adjust to bring about fullemployment in the labour market. We further saw that Keynes provided an alternative model and we examined in detail the role of interest rates in the Keynesian model. We noted the extreme case of the liquidity trap where investment could not be induced by further falls in interest rates and noted Krugman's use of this in explaining Japan's prolonged economic crisis. Keynes' objective was to build a model that would convince economists that economies can operate at under full-employment equilibrium and would not necessarily tend to full-employment equilibrium as the Classical model contends. If Keynes was correct this could be seen as the basis for government intervention in the economy, i.e. government policy to influence the working of the economy. The Keynesian argument led in turn to the development of a defence of the Classical approach, in particular, it led to the restatement of arguments that 'government intervention' was unnecessary and perhaps downright harmful to the economy. We shall consider an important part of this Classical defence in terms of Milton Friedman's expectation augmented Philips Curve analysis - see Acocella, section 7.4.4, pp.143-162. Friedman and the monetarists conceive the market economy as intrinsically stable, unlike Keynes and the Keynesians. They do not deny that instability may exist in real life situations but they attribute it to government interventions rather than to the fundamental state of the market economies. In developing our understanding of Friedman’s alternative analysis to Keynes, I want us to clearly understand two of 1 of 5 EC301 Macroeconomic Policy Dr. Derick Boyd Friedman’s theoretical constructs that are fundamental to what became the monetarists’ approach: (i) Friedman’s restatement of Irving Fisher’s Quantity Theory of Money that we examined in a previous essay; (ii) Friedman’s Expectation Augmented Phillips Curve.1 This theory postulates a causal, direct and proportional relationship between the quantity of money and the price level, assuming a constant level of money velocity. Friedman’s restatement starts with the Fisher equation rewritten as MV = PT, where M is the quantity of money, V velocity, P the price level and T transactions. If we exclude financial transactions from T and consider the structure of the real economy as given, we can replace T with income Y , which we can see as aggregate market output or equivalently the aggregate real income of the economy. Since T has been replaced by Y then V is no longer the transactions velocity of money, but rather the income velocity of money. So we can write MV = PY where PY would represent nominal income and if M is the quantity of money then V is the income velocity of money (the number of times the money circulates to accommodate the particular nominal aggregate income). Furthermore, if we replace velocity with the fraction of income individuals wish to hold as money balances, k (the inverse of velocity), we can rewrite the Fisher equation as M=kPY - the form of the Friedman restatement2. If k is constant as Friedman assumes, changes in M will be reflected in nominal income, PY. Friedman considers money as one of various forms of wealth. It is not, as it is for Keynes, an alternative to fixed interest securities only – explained in the liquidity preference theory of money we examined earlier. For Friedman, money belongs to the entire spectrum of assets, both financial (of various maturities and forms) and real (individual durable goods like land, houses, gold, firm’s assets...). Within this framework, changes in the nominal quantity of money – at initially given prices – will cause changes in the real quantity of money, changing spending on securities and real goods. It is precisely the real balance effect that serves as the transmission mechanism of monetary policy according to Friedman. So, based on this restatement of the Fisher quantity equation, Friedman argues that changes in the money supply are the principal systematic determinants of the growth of nominal income. Friedman does not say that changes in money just all go into inflation however. As Acocella (p.143) states, there is a “seemingly greater openness of neo-quantity theorists to the possibility that money does not affect just prices but also real income in a limited way”. There is a sting in the tail, however, for Friedman goes on to show that changes in money can only affect real income in the short run and will always be associated with increased inflation. So government intervention is not benign as the Keynesian approach indicates – allowing coordination problems and market failures to be corrected. For Friedman, even if income and employment can be increased through government intervention, the cost of those increases is inflation 1 There are two aspects to this, the first is that you should be able to understand and explain this as a technical device, and the second is that you should be able to place it in the context of the development of the macroeconomic policy literature. 2 In order to really understand the meaning of k fill in some numbers in the equations LsV pY and convert it to the final form Ls kpY , it is really quite simple. 2 of 5 EC301 Macroeconomic Policy Dr. Derick Boyd and the increases will only last a short while. Friedman’s explanation of this resides in the second technical construct that I wish us to examine in the Expectation Augmented Phillips Curve. Let us examine in detail the behaviour of the market unemployment rate using the ‘expectation augmented’ Phillips Curve. The original Phillips curve (which was statistically observed in Phillips 1958, and is widely used by Keynesians) is the inverse relationship between the rate of change in money wage rates, w , and the unemployment rate, u , where the relationship is written as w u , with 0 . According to Friedman, this relation is unlikely to remain stable over time. Figure 1 r/g wage inflation Phillips Curve r/g unemployment U* The curve as developed by Professor A.W. Phillips and employed in Keynesian analysis was regarded as showing a relationship between inflation an unemployment that could be described as a trade-off relationship, see Fig 1. It was for a while thought as showing that governments could trade off some unemployment for some inflation - i.e., governments may choose to have low unemployment and higher inflation or they may choose to have a lower rate of inflation and higher unemployment. The Phillips curve may be seen, therefore, as underlying the notion that there is a role for government intervention. This relationship occupied an important place in macroeconomics until the 1970s when economies started to experience both high unemployment and high inflation - so no trade-off seems to exist. The persistence of stagflation indicated that this relationship, even if existed before, obviously did not hold anymore. The attack on this Keynesian notion and the development of a theory to explain stagflation was established my Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps in the form of the expectation augmented Phillips curve analysis. This would again represent a return to the more classical notion that the economy will tend to a 'natural full- 3 of 5 EC301 Macroeconomic Policy Dr. Derick Boyd employment output' level of operation - how this is defined we will learn in what follows3. Figure 2 r/g wage inflation U*=NAIRU r/g unemployment PE2 U/ PE1 * U PE0 Friedman does not refer to 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' unemployment. 'Voluntary' unemployment is replaced by 'the natural rate of unemployment'. This is now the level of unemployment associated with market clearing. It allows for unemployment caused by structural factors. The important point about the natural rate of unemployment, however, is that it does not include unemployment caused by lack of aggregate demand. Thus, the government cannot reduce the natural rate of unemployment by increasing aggregate demand. It is worth noting some things from Acocella's account. Firstly, the two crucial assumptions of the Friedman/Phelps model are (p. 144): (i) expectations are adaptive; (ii) firms are better informed than workers are about price increases and that (iii) also implicit in the original Phillips curve is the assumption that expected inflation is zero. That is, workers always assume that the existing money wage equals the real wage. Tutorial Questions 1(a) Explain Irving Fisher’s quantity theory of money and Friedman’s restatement of the Fisher equation. What, if any, additional insight does Friedman’s restatement provide? (b) Acocella writes, "Friedman and the monetarists conceive that market economy as inherently stable. Monetary policy is effective only in the short run; in the long run there is no trade-off between inflation and 3 There are two aspects that we need to bear in mind, one is the internal consistency of the theoretical device (the expectation augmented Phillips curve in this case), and the other is the context in which theory developed and the role it plays in establishing a competitive macroeconomic paradigm. 4 of 5 EC301 Macroeconomic Policy Dr. Derick Boyd unemployment." Explain Friedman's and the monetarists' argument and its relationship to the Keynesian proclivity to interventionist policies. 2. For Friedman and many monetarists, government intervention is never benign - even if income and employment can be increased through government intervention, the cost of those increases is inflation and the increases will only last a short while. Elucidate and explain. ********* 5 of 5