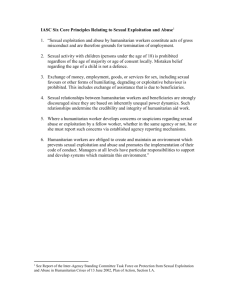

prevention, protection and recovery of children from commercial

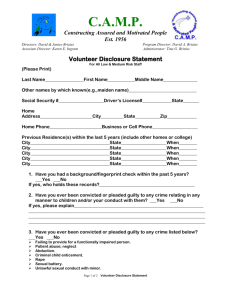

advertisement