discoveries100.doc

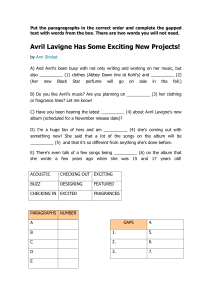

advertisement