The Problem of "Free Will" and "Determinism"

advertisement

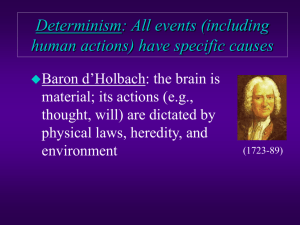

The Problem of "Free Will" and "Determinism": see text pp. 164-68 the key question is whether the human element in the universe is the "captain of its own fate" in any meaningful sense we experience two opposing features of our behaviour and decisions: we are aware of our own freedom, the ability to decide for ourselves; and yet … we discover that in many cases what we believed to be a free decision at the time to have been influenced by various personal & social factors that at least impaired our freedom, and perhaps vitiated it (upbringing, education, environment, biology, etc.) e.g. vocational choices; nullity cases Complexities: most of our judgments about people assume that, in some sense, they freely chose to do what they did we punish, condemn, or blame people for making certain kinds of choices, and insist that they should have done something else much of our legal system is based on this approach at the same time, modern psychology is making us more and more aware that this assumption is often erroneous psychiatrists testifying at criminal trials have tried to show that defendants, having been abused, or victimized by circumstance, or "under the influence" (of propaganda, extreme emotional stress, alcohol, etc.) cannot be held morally responsible for actions inspired by factors beyond their control this is clearly seen during times of war, when people do all kinds of things they would not ordinarily do in peacetime because they are subjected to all kinds of pressures that either force them to perform the actions, or alter their conscious moral framework so that they "choose" acts previously considered morally wrong we are much less inclined to judge harshly when, as in these cases, it can be shown that someone's actions were involuntary -- this is why we distinguish between types of crime and degrees of guilt In view of all this, the metaphysical problem of free will hinges on the question whether a belief in human freedom is consistent with our experience, our knowledge, and our views about human nature. Arguments for Determinism: in some religious traditions, belief in an all-powerful, all-knowing God has led to the conclusion that he/she/they can foresee and control (predetermine) everything that takes place any event that God did not know about in advance, no matter how small and insignificant, would imply a limit on divine power inconsistent with is believed to be the nature of God if this is the case, God must have known every choice that we would ever make in the course of human history - everything that anyone has done/is doing/is going to do is predestined and predetermined and “controlled” by God's prior knowledge and decisions Note: this is NOT a Catholic point of view! (cf. Fr. Barron re: “The Adjustment Bureau”) there is a metaphysical argument: Every event has a cause. If one accepts this principle, then everything, including our thoughts, must have been caused by something else. Even if one is a "soft" determinist and looks for the cause of mental events within the individual, those events are still being caused strongest and most convincing are the arguments from scientific investigation in the factors that influence or determine human behaviour research into psychology, physiology, neurology, pharmacology, biochemistry, biophysics, etc., allows us to make more and more accurate "profiles" of people to predict their future behaviours Arguments for Free Will: chaos theory and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle both assert that there is an irreducible element of unpredictability in nature -- this doesn't "prove" that free will exists, but it argues against the predictive certainty of determinism our moral and legal judgments only make sense if we are free agents, at least to some degree -- religion in particular becomes absurd if we are not free (What's the point of God condemning us for sin, and then later offering us salvation, if we don't act freely? It's just a puppet show.) William James offered two arguments in his famous essay, "The Dilemma of Determinism". People experience remorse, and regret that they did or believed certain things, and they wish they had done or believed otherwise. What sense does this make if all our thoughts and actions are predetermined? We attribute responsibility to people, and punish them for not exercising it properly. This makes no sense if we are not free. We don't punish the rock against which we stub our toe, because we don't think the rock is a responsible, free agent. Why then do we punish people, if they could not have acted other than they did? Finally, there is this point: if determinism is true, then determinists ought simply to figure out what factors cause philosophical decisions in us, and then employ them (whether that means hitting people with clubs, getting them drunk, or whatever). But determinists do not in fact do these things. Instead, they argue their point of view – which makes no sense unless there is some element of freedom in human behaviour.