Time Management - Academic Skills & Learning Centre

advertisement

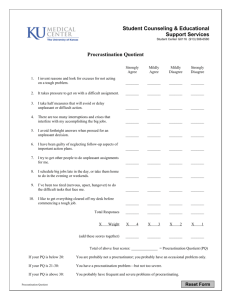

1 TIME MANAGEMENT Time Management at University The University academic year generally lasts for 26 weeks, plus exam periods. The first week of each semester is usually spent introducing the course/discipline, sorting out tutorials and labs etc. This leaves 12 weeks during which most courses will cover the required material. Don’t be lulled into a false sense of security by the leisurely pace of the first two weeks. You’ll need to keep up with lectures and reading from the very beginning otherwise, when you need to add assignments and preparation for exams, you’re likely to be overwhelmed. Of course, you will need to manage you time differently if you are engaged in research only. This means that you will need to manage your time at a number of levels: the semester level, the weekly level and the daily level. You also need to consider the best places for you to work as well as strategies for overcoming procrastination. Time management is ultimately an individual activity that we all approach differently, but it helps to know your own strengths and weaknesses in this area. Assessment of Current Time Management Skills Before embarking on a time management plan, assess and analyse your current time management skills. Exercise. Analyse when, where and how you study most effectively and efficiently. Item When do you study best (morning, daytime, evening)? Where do you study best (library, university, home)? How do you study best (length of study, types of task, timing)? Analysis and notes 2 Exercise. Complete the following time management questionnaire. Based on your responses above, list some strategies for areas that need work. Area Are you always behind and trying to catch up? Needs work? Yes No Do you make a written ‘to do’ list every day? Yes No Do you avoid striving for perfection on tasks that don’t require it? Do you have time for yourself? Yes No Yes No Do you group similar projects together? Yes No Do you set realistic deadlines for yourself? Yes No Do you break large projects into smaller, more manageable tasks? Do you leave for appointments 10 minutes early? Yes No Yes No Do you schedule disagreeable jobs between agreeable ones? Do you carry books or smaller projects with you so when you do have to wait, you can do something productive? Do you take advantage of bits and pieces of time that become available during the day? Do you reward yourself when you have managed your time well? Have you started a lot of projects that you can’t seem to complete? Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No Strategies 3 Semester Plans The Semester Plan should include all your assessment commitments for the semester, e.g. assignment deadlines, tests, exams, etc. This allows you to see them all at a glance and plan ahead for busy periods when many things are due at once. The ANU Wall Planner already notes in the teaching breaks, public holidays and exam periods, so to this you need to add the specifics for your own courses. It might be useful to start by listing all of the assessment for each subject (you should be able to get this from your course outlines) and then use some kind of colour code (pens, stickers etc) to distinguish between your different subjects when marking them on the Wall Planner. Work backwards from your deadlines. Schedule to finish study tasks at least a week before they are due. Weekly Schedules The weekly schedule should be a whole-of-life plan rather than just a study plan. You will need to include your regular university commitments (lectures, tutorials, labs, meetings, etc.) as well as any other commitments you may have (paid work, clubs, sport, fitness classes, language classes etc). You should also allow times for housekeeping, shopping, socialising and leisure. Everyone has unique commitments that may be influenced by family obligations and health issues. Your weekly schedule should reflect your particular life needs and circumstances, not what you wish they were. Step 1. Mark in all of your set class times for uni. Step 2. Mark in anything else that you have to do at a particular time. Step 3. Assess where the gaps are in your schedule and decided what is the best activity to do in that space. To do Step 3 effectively you need to have a list of all the thinks you need to fit in to your week, and a good sense of all the individual activities that go into ‘studying’ for university. Exercise. List the activities you need to ensure you include time for in your weekly schedule. Discuss in pairs. Non Study Activities Study-Related Activities 4 Once you have a list you can start allocating activities to spaces in your weekly schedule. Remember to: Consider what times of day you are most alert. Try planning your time so that you do the more difficult tasks when you are most alert (for example reading and notetaking), and do less demanding tasks when you are tired (for example re-writing notes). Make sure you take a short break every hour to refresh you mind and body. Leave time for food and exercise. Regular physical activity — a walk, a visit to the gym, a game of tennis, whatever you enjoy—helps you clear ‘the cobwebs’ and to think and work better. Similarly, ensuring you eat a good balanced breakfast, lunch and dinner—rather than skipping meals for lack of time—also helps your body and mind work more efficiently through the day. Be realistic about how long things actually take. Consider travel time and down time to relax once you get home. How long will certain study activities (reading, finding sources, writing your essay) actually take? Your first few plans may turn out to be unrealistic because of misjudging these things. Don’t be disheartened – learn from them to make a more realistic schedule for the following week, it can take time to get the balance right. Be realistic about your goals and your ability to meet them. Setting goals that are either unlikely or impossible for you to meet will only undermine your confidence in your ability to manage your studies. Manage your study and research time not for the ideal you, but the real you. Allow room for the unexpected (illness, sudden visitors, friends in need, homesickness etc.). You are not programming a machine when you timetable, you are setting out a realistic as well as flexible plan of work for the coming week. The best timetable is the one that gives you sufficient padding for when the unexpected happens. So don’t schedule every minute of every day or schedule time to do nothing! Consider the flow of the university week. You are required to complete the assigned reading before the tutorial, so make sure you schedule your time to read accordingly. Also ensure you have time to answer any tutorial questions before the tutorial – not only will you get more out of the class and be able to contribute better but you will have the opportunity to ask your tutor about any questions you were unsure of. If you don’t prepare fully for the tutorial you may miss your opportunity for clarification, and next week’s work will probably build upon the current week – if you get behind it’s difficult to catch up. Be as specific as possible about the task you are trying to achieve in the allotted time. Don’t just write ‘study’ because, as you saw in the activity above, there are many different activities that make up study. You don’t want to waste time working out what to do once you sit down at your desk. It’s better to write ‘read 3 allotted articles for economics’. Keep track of activities you don’t finish. You will need to come back to them in some of your spare time. Prioritise. If assignments are due, you may have to allocate more time to completing them than revising for exams this week. You schedule should not be the same every week – it should reflect the changing priorities of the semester. Start revising for exams from day 1. It’s a good idea to allocate some time every week to revising your notes for each subject so that you identify problem areas and have plenty of time to learn the material. As the semester goes along you will need to allocate increasingly more time for this as you have more material to revise and the exams are getting closer. It may help to think of yourself as a university worker… A good way to approach your university studies is to think of yourself as a university worker, with a worker’s sense of responsibility and accountability to work. The typical full-time workload in Australia is 40 hours a week. So transfer this principle to your studies (or if you are studying part-time, the appropriate portion of that full-time load.) A weekly plan that has you ‘at work’ from 9am to 5pm (or an equivalent to match your preferences, for example working better in the evenings) will provide you with a strong basis for structuring your study time. There will almost certainly be times through the semester when you will have to stretch your 40-hour schedule to ensure you keep up with all your study commitments: assignments, exam preparation, etc. By drawing a line around your ‘study life’, you will find that this schedule will free you (and your conscience!) most evenings and weekends to do other things with your time. Of course, if you are working while studying full-time, you will need to factor that in too. 5 Weekly schedule Date range: ............................................................ Week No.: .............................................................. Monday Tuesday 8am 9am 10am 11am 12pm 1pm 2pm 3pm 4pm 5pm 6pm 7pm 8pm 9pm Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 6 Daily ‘to-do’ Lists A Daily ‘to-do’ list outlines what you need to accomplish during the course of the day. Follow these steps: 1. Write a list of activities that you want or need to accomplish during the day. 2. Break down larger tasks into smaller ones. 3. Prioritise and list the most important tasks first. 4. Check to see if there are any activities that you can accomplish at the same time. People often find they have a long ‘wish-list’ of things to do – more things than can realistically be done in a day. Because it is impossible to achieve all of them in a day you can start to feel like you’re not getting anywhere. Keep a list of all the things you wish to do if you like, but this is not the purpose of the daily to do list. The purpose is to keep track of the most important things you need to get done today. Consider limiting your list to only 5 items so you are forced to prioritise! Remember, just like your weekly schedule, this should take a whole-of-life approach, so if the most important thing to do today is go grocery shopping so you have food for tomorrow, this goes at the top of the list. Manage Your Place Along With Your Time Where you plan to do your studies is as important as when and how. Designated study spaces on campus—libraries mainly—are the obvious choice. Some students prefer to work from home, or their college rooms, and some have to because of work and family commitments. Choosing a favourite study corner in your favourite library as your study space and aiming for it by 9am might prove a useful incentive to getting you into ‘study mode’ each weekday morning. Remember though, that you need to match your study place with your study task. Libraries are great for looking for resources or reading, but may not be best for writing assignments as you need to carry all your resources with you, and you may not have good access to a computer. Overcoming Procrastination What is Procrastination? Procrastination is the avoidance of doing a task that needs to be accomplished. This can lead to feelings of guilt, inadequacy, depression and self-doubt among students. Procrastination interferes with the academic and personal success of students. Why do Students Procrastinate? Poor time management. Procrastination means not managing time wisely. You may be uncertain of your priorities, goals and objectives. You may also be overwhelmed with the task. As a result, you keep putting off your academic assignments for a later date, or spending a great deal of time with your friends and social activities, or worrying about your upcoming examination, class project and essays rather than completing them. Difficulty concentrating. When you sit at your desk you find yourself daydreaming, staring into space, etc., instead of doing the task. Your environment is distracting and noisy. You keep running back and forth for equipment such as pencils, erasers, dictionary, etc. Your desk is cluttered and disorganised and sometimes you lay on your bed to study or do your assignments. Fear and anxiety. You may be overwhelmed with the task and afraid of getting a failing grade. As a result, you spend more time worrying about things than completing them. Negative beliefs such as: "I always do poorly in exams" or "I don’t know how to write a lab report" may allow you to stop yourself from getting work done. Personal, family and relationship stress. 7 Finding the task boring. Unrealistic expectations and perfectionism. You may believe that you MUST read everything ever written on a subject before you can begin to write your paper. You may think that you haven't done the best you possibly could do, so it's not good enough to hand in. Fear of failure. You may think that if you don't get a High Distinction, you have failed. Or that if you actually do fail an exam, you, as a person, are a failure, rather than that you are a perfectly ok person who has failed an exam. How to Overcome Procrastination Consider the cause of your procrastination. Is it anxiety, difficulty concentrating, poor time management, indecisiveness, perfectionism, or a lack of clarity about the task itself? Identify your own goals, strengths and weaknesses, values and set priorities. Motivate yourself to study: think about what you want to get out of the course or activity. Ask questions to clarify tasks and assignment questions so you can get started. Break the task into small parts and do them one at a time. Study in small blocks instead of long time periods. For example, you will accomplish more if you study/work in 60 minute blocks and take frequent 10 minute breaks in between, than if you study/work for 2-3 hours straight, with no breaks. Reward yourself after you complete a task. Try studying in small groups. You can help and test each other, and can break up all the individual study you do with a more social setting. Keep a checklist and mark off tasks as you complete them. Set realistic goals. Modify your environment: eliminate or minimise noise and distraction. Ensure adequate lighting. Have necessary equipment at hand (don't waste time going back and forth to get things). Don't get too comfortable (eg. reading on the bed) or you might fall asleep! A desk and straight-backed chair is usually best. Take a few minutes to straighten your desk so it and your mind are uncluttered. Exercise. Analyse your procrastination practices and behaviour. What situations lead to your procrastinating? Why do you procrastinate? Having analysed why you procrastinate, think up some strategies to help you overcome procrastination. What I do to avoid study/work. Why I procrastinate Strategy to overcome procrastination 8 Affective Factors Relating to Time Management for the Phd. THIS INFORMATION MAY ALSO BE HELPFUL TO NON-PHD STUDENTS Enthusiasm During the first year of the PhD, enthusiasm is high, so too is motivation. This, paradoxically, can have a negative impact on your time-management planning. For example, you may make “overambitious estimates of what [you] could accomplish during the first year”.1 As a result, too many tasks may be crammed into the time-management schedule. Doing this, in turn, may then result in feelings of stress when deadlines are missed or tasks are not completed. Therefore, make your research goals and deadlines realistic rather than optimistic. Enthusiasm may also lead to a dangerous sense of having ‘all the time in the world’, when the time you have to complete the PhD seems to be long time away. Talking with later-year PhD candidates will quickly disabuse you of that notion. One of the dangers of thinking that three years is a long time is that you may eventually put too much pressure on yourself to complete research in the later years. The quality of the research may also suffer, as it did in the case of this second-year biochemistry research student: I’m aware that I’ve only a year left and two years have already gone. Three years doesn’t seem half long enough; it seemed a long time in the beginning. Now I’m trying to finish off groups of experiments and say ‘that’s the answer’ rather than exploring it more fully, which is what I used to do. 2 Your enthusiasm for your research may wane. Working on a research problem for three years can lose its lustre. Diminished enthusiasm for your work can result in diminishing motivation, which can make it harder to work to deadlines and to achieve goals. At the end of the first year, you may be surprised or disappointed with how much reading, research and writing you have or have not done. Isolation Although you might be working in a sizable discipline or department with a reasonably sizable group of postgraduate students, intellectual isolation can set in and this can affect your time-management plan. Your research may be so specialised that you feel you share “little in common with others in [the] department”3 and hence feel disengaged from others, even if you work in a laboratory or share office space with others. A sense of intellectual isolation can result in poor motivation, “a loss of interest” in research, which can effectively reduce one’s work-rate. A dysfunctional relationship with a supervisor can also create a sense of isolation and a reluctance to communicate your ideas. Dependency Initially, you may be reliant on your supervisor for approval, direction and feedback, but if this reliance persists then the research process can take longer than you anticipate and it may put a strain on your relationship with your supervisor. For example, if you need to continually consult your supervisor for advice, then that may add time to the research process. So, too, will suspending research while you await feedback from your supervisor on a previous draft. Being autonomous is good for you and your time-management plan; it’s also good for your supervisor. Boredom and Frustration At various points throughout your study you may have to be rescued from boredom. You might be sick of your work or feel that it is tedious, useless or going nowhere. This is a natural part of the study process; focusing on a particular research problem for a long time can become monotonous and repetitive. This boredom can also be compounded by a sense of frustration at not being able to digress from the research topic: “Not being able to follow up results, ideas and theories is a constant source of dissatisfaction and frustration for most postgraduates at the end of their second year”.4 File away those interesting ideas and theories for another time – maybe for a conference, a journal article, a book review, or, if it’s a really big idea, the post-doctoral fellowship! Estelle M. Phillips and D. S. Pugh. 1994. How to get a PhD: a handbook for students and their supervisors 2nd ed. Buckingham: Open UP. 73 1 2 ibid. 83 ibid. 74 4 ibid. 78 3 9 Flexibility: allow for the unexpected Your weekly and monthly schedule should also allow for the unexpected: illness, sudden visitors, friends in need, technical stuff-ups, boredom and homesickness. More importantly, “because the unanticipated is in the very nature of research”5 you may find that what you had planned to achieve in the next week or month or, worse still, months is no longer possible. Research may lead you in an unexpected direction, so revising your time schedule is something you may need to do on a regular basis. You are not programming a machine when you timetable, you are setting out a realistic as well as flexible plan of work for the coming week or month. The best timetable is the one that gives you sufficient padding for when the unexpected happens. “Detailed plans inevitably need regular amendment”. 6 In the case of the unexpected, have a “to do” list handy so that you use your time productively doing things that you may not yet have had the time to do. If a deadline passes and the work hasn’t been done, find out why. “You might estimate how much was due to circumstances that could neither have been foreseen nor prevented, and how much was due to your own inexperience, inactivity or inability to estimate the amount of work accurately. This last is the most usual discovery”.7 Pat Cryer. 2000. The Research Student’s Guide to Success 2nd ed. Buckingham: Open University Press. 109. ibid. 106 7 Estelle M. Phillips and D. S. Pugh. 1994. How to Get A PhD: A handbook for supervisors and their students. Buckingham: Open University Press. 88. 5 6