THE DEATH OF IVAN ILYCH

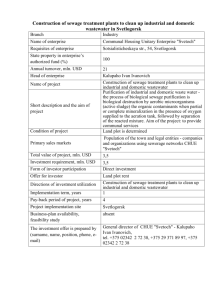

advertisement