RESTORATIVE CHILD PROTECTION

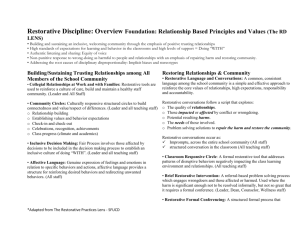

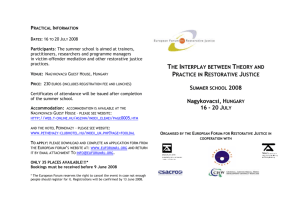

advertisement