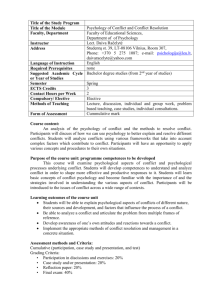

Basic Concepts and Theories

advertisement