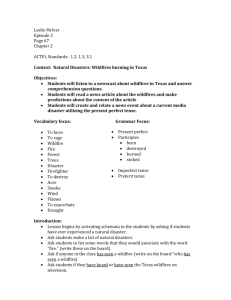

2011 Texas Wildfires Common Denominators of Home Destruction

advertisement