on the mode of communication of cholera

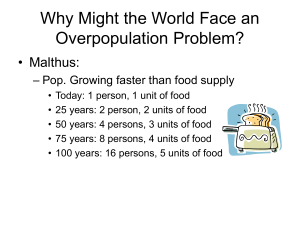

advertisement