Chairwork with the mode model - the International Society of

advertisement

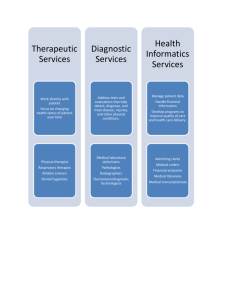

Chairwork with the mode model by Eckhard Roediger M.D. Online paper posted December 2012 on the ISST website (www.ISST-online.com) Introduction Gestalt therapy works with modes or persons on different chairs, depending on which parts are prominent in the session. The Gestalt chairwork reacts very flexible on the patient´s current situation and helps to clarify the patient´s inner world. It is basically following the process. Chairwork can be applied in a more strategic and systematic approach too, when it is connected with a case conceptualization e.g. the Mode Map (Roediger 2012a). Young et al. (2003) described four general type of modes: ¾ Child Modes: Essentially they are primary or basic emotions such as anger, fear, happiness, surprise, disgust and grief (Ekman 1993); closely related to bodily sensations (Damasio 1999) ¾ Dysfunctional Parent Modes: Resulting from internalized appraisals of significant others inducing core beliefs and reoccurring as negative automatic thoughts (Beck et al. 1979) ¾ Maladaptive Coping Modes: Visible behavior as persisting coping reactions to early childhood experiences accompanied by secondary emotions such as hatred, superiority, shame or guilt. ¾ Healthy Adult: Adaptive self regulating function, composed of 3 steps: mindful self awareness, detached reappraisal and functional self instructions (Roediger 2012b). All modes are “composed” by a combination of schema activation and coping behavior. In everyday life coping modes are dominant, resulting from coping styles and accompanied by secondary or social emotions. This happens on the “front stage”. Coping modes are elaborations of the biologically based fight/freeze/flight/surrender behavior (See bottom line of fig. 1). Each coping mode fulfills different core needs and has an interpersonal “meaning” defining the relation with another person: Either I am on top (overcompensator - striving for control – “topdog”), I surrender (to gain attachment – “underdog”) or I withdraw from a relation passively (detached protector as “freezing” behavior to avoid harm) or actively (detached self soother as “flight” reaction to protect myself or gain lust). The goal of the coping mode itself is not generally dysfunctional, but the attempts to reach it are too strong, too rigid, alternatives are lacking or they appear disintegrated in a “flipping” way. “Backstage” and usually not visible child and dysfunctional parent modes are activated too leading to action. Acting out a child mode is perceived as “childish”. The directing core beliefs remain covert as well. In a child mode the activation of unconditional schemas lead to strong and overwhelming emotions and induce coping impulses. Child modes energize the person. You find the polarity of the two main child modes in the left side of the middle section of the Mode Map (Fig. 1). In a dysfunctional parent mode the activation of conditional schemas activate harsh appraisals and display rules suggesting inducing related coping behavior. Parent modes 1 direct the primarily undirected energy of the child modes towards the self or others. You find the parent modes on the right hand side of the middle section of fig. 1. The forth mode is the healthy adult. He or she is in charge for adequate self regulation balancing the personal needs with the needs of others. Therefore he or she has to detect and reappraise the internalized values and rule sets and take care for the core emotional needs of the child modes. This heals the schemas. E. Roediger functional / integrated flexible reaction Team playing Cooperation Sensitive Child (Socializing) Self control Limit setting Self soothing Self support Self Directed directed to others Readjusted Wothsand Goals Empowered Child (Action) Healthy Adult Satisfying Core Needs dysfunctional / desintegrated (self-regulation) Vulnerable / anxious Child Angry / Impulsive Child Attachment Control Compliant Surrender Following goals adequate demanding Reappraisal/ “Impeachment“ Demanding and Punitive Parents Self- Directed directed to others Introject Detached Protector Detached Self-soother internalizing / autoplastic Model Overcompensator (Dominance) externalizing / alloplastic Putting the modes on the chairs – getting “backstage” Each chair represents one type of modes. The position in the room represents the order on the Mode Map (fig. 1). The working space in the therapy room is related to the mental representation of the mode map in the brain. In therapy we start with identifying the coping modes. While reporting about their life patients usually are in one of the coping modes in the given spectrum between surrender – withdrawing or trying to be dominant as described above. The therapist labels the coping mode first and then validates them as the best solution learned from prior experiences in the past. This is what happens on the front stage. Now the therapist tries to get through to the backstage in the direction of the primary emotions of the child modes or the latent beliefs of the parent modes. Questions leading to primary or basic emotions behind the coping modes (close to bodily sensations) are: “While you are telling me that, what do you feel in the body?” and “What does this feeling really wants to do if nobody would see it?” Usually patients name secondary or social emotions first. They include automatic appraisals and belong to the coping modes. A question helping to differentiate between secondary and primary emotion is: “Were you 2 born with these feelings?” Primary emotions are inborn (Ekman 1993). This question reveals the parental appraisal that are incorporated in the secondary emotions. In case people have difficulties in naming their primary emotions the therapist might offer a choice of the basic emotions named by Ekman (1993): grief and anxiety belong to the vulnerable child, anger and disgust to the angry child. Once the primary emotions are detected they are placed on the child chair. It is helpful to have a child chair for both, the vulnerable and the angry child mode, because they have different needs and goals. Beside the primary emotions the coping modes contain the beliefs of the parent modes are shimmering through too. A question accessing the core beliefs are: “What does the voice in your head really say?” In the beginning this appraisals are completely ego-syntonic. Desidentification is induced by formally changing the “I”-form into a “you”-form: Instead of “If I don´t get that made, I am a failure!” the wording is transformed into: “If you don´t get that made, you are a failure!” The upcoming appraisals are placed on the parent mode chair and labeled as demanding or punitive parent modes. Splitting up the coping modes into an emotional (child mode) and a belief part (parent mode) “sets the stage” for working with the child and parent modes while we have entered the “back stage”. Here an example: Th.: How do you feel when you failed the exam? Pat.: I felt guilty (which is a secondary emotion). Th.: Ok, but you were not born with this feeling. What do you feel deep inside, in your body? Pat.: I feel suppressed and sad. Th.: Right! Feeling sad is a basic emotion. What presses you down, what does the voice in the head say? Pat.: I have to get it made, otherwise I am a failure! Th.: OK. The voice says: You are a failure (The therapist changed the wording form the egosyntonic “I”-form to the ego-dystonic “you”-form). This is the voice of the punitive parent mode. Let´s place this voice here. And we put another chair here for the sad and suppressed child mode feeling (The therapists adds the two chairs for the “backstage”-work). Now please sit down on the parent mode chair and say this again to the child mode chair. Pat.: You are a failure if you don´t pass the exam!! Th: Well. Change to the child mode chair now, please. (The patient changes chairs). What do you need when the voice talks this way? Pat.: I need someone to protect and support me? Th.: Right! This is the job of the healthy adult! (Now the therapist could stand up together with the patient and start the change work). 3 Working “back stage” – understanding the patient´s inner world Once the coping mode is passed by the polarity of child and parent modes shows up between the two chairs. Usually in a given mood state one child mode is dominant leading to the presented coping mode: If the vulnerable child is activated the patients tend to surrender or detach (left side of the coping mode spectrum in the bottom line of fig. 1). If they turn more into an angry child their bodily activation strives for dominance or at least detached self soothing (right part of the bottom line in fig. 1). As long as the patient has access only to one part of the full emotional spectrum he or she is trapped in their current coping mode. So accessing both child modes is crucial to enable the patients making use of their resources and get out of their life trap. Here two examples how to bypass the coping modes: Bypassing a detached protector: Pat.: Sorry. I don´t know what you mean. I don´t feel anything right now. There is just fog in my head. Th.: OK. This is what we call a detached protector. He protects you from bad feelings. This was helpful in the past i.e. when you were a child and couldn´t do much. Let me ask the detached protector some questions to better understand what he is good for? Pat.: OK. Th.: How long do you already exist?….What are you preserving (the patients name) from? ….What should never happen here in therapy? (The patient´s answers lay traces to the hidden fears of the child mode and the rules and expectations of the parent modes. The therapist first validates the DP for his efforts in the past and then asks him, under which conditions he permits him or her to work with the other parts of the self. It is important to reassure the DP that he can come back after the session. But for progress in therapy some experiments under the therapists control are inevitable. Then the therapist either goes with the fears of the child or the expectations of the parents and places additional chairs behind the DP according to the position on the mode map (fig. 1) if you look at it from the bottom end. In this example he begins with the emotional side): Th.: Let me ask the vulnerable child inside of you how it feels behind the detached protector (the therapist places an additional chair and asks the patient to move to this chair. “How do you feel behind the detached protector wall?” Pat.: I feel save! Th.: Right! This is what the DP is good for. But let me place another chair beside you (the therapist adds a chair for the angry child mode). Let me ask you: What are your dreams about life. Do you want to stay behind this wall for the rest of your life? (While saying this the therapist pushes the DP chair softly against the knees of the patient making his space even smaller. Usually the patients feel uncomfortable an strangled by the DP chair now and try to push it back again. The therapist immediately reacts on that impulse). Th.: Hey, what is that impulse?! Look what you are doing! What do you feel right now? This is not the vulnerable child anymore! This is different: This is the angry child now. Welcome! What do you need? What would you like to do? 4 Pat.: I need more space (etc.) Th.: Ok, you are right! The wall that once protected you now turns into a prison wall. You want to get out of that prison. But what does the voice in your head comment on these ideas? Pat.: I cannot do that, I will never succeed, I am to weak (etc.) Th.: Ok, this is not the Child´s voice any more, but the parent´s voice. Please move to this chair (the therapist adds a parent mode chair and ask the patient to take a seat over there). Th. (talking to the parent mode chair): Ok. Please repeat what you think about little (name of the patient). Pat.: You cannot do that, you will never succeed, you are too weak…. Th.: How do you feel hearing these voices? Pat. (Gets either weak or angry and the therapist ask him or her to move to the adequate child chair). Th. (to the child mode): Ok, this is what the voice in your head makes you feel. What do you need no to get out of this trap? Pat. (names his or her needs). Th.: Ok, now we know, what the healthy adult has to take care for! (At that point the change part begins). Bypassing an overcompensator Pat.: They are all idiots around me. I want to fire them all!!! Th.: Ok, this sounds a bit angry. Is it possible that you are a bit in a fighting mode? Pat.: Don´t bother me with your therapist´s shit! This is just the bare truth!! Th.: Ok. Let´s go with the “fighter”: What would you like to do if there were no witnesses? Pat.: I would kill the whole office! Th.: Ok! Kill them all. What do you feel in your body right now? Pat.: I feel very strong! Th.: Right! You fell the power of the angry child mode in you! And what does the voice in your head say? Pat.: I am right! They deserve to be treated that way. Th.: Ok. You have killed them all. What will happen tomorrow when you come back to your office? Pat.: Ups – there will be nobody there… Th.: Right! You hesitated a bit before you answered. What came up in that moment? 5 Pat.: I was irritated… Th.: Ok, so let´s move to this chair here (the therapist puts two chairs behind the overcompensator chair the patient was talking from before and asks the patient to take a seat on the VC chair). Th.: When you were killing all your employees you were in the angry child mode. Now when they are all gone and you are left alone the more sensible child part comes up again. What do you really need? Pat.: I hate to admit it but at least I need them… Th.: Oh, this is the voice in your head saying that they hate to admit it. (The therapist puts an additional chair behind the overcompensator and asks the patient to sit there). Th.: A moment ago when you all fired them the voice in the head was turned to them putting them down. Now the voice has turned to you and puts you down, because you need the help of others. What do you expect him to be like (talking to the parent voice and pointing to the child chairs)? Pat.: you have to be strong and do it all by yourself. They will all leave you anyway. You cannot rely on anybody but yourself! Th.: Very good. How does that feel hearing this voice? Pat.: It makes me sad and lonely… Th.: Ok. Now we are in touch with the vulnerable part of you. Please come here (Patient moves to the VC chair). What do you really need? (At that point the change part begins). Creating new adult solutions – the change part The new solutions are not induced on the backstage level. To switch into the change phase therapist and patient both stand up and stand side by side. They now form a “reflecting team” (Anderson 1987) to create new ideas on a healthy adult level. This supports changing the functional activation state of the brain and gives access to latent resources within the patient. Changing the working level helps to distance from overwhelming emotions. Standing side by side provides a “joint referencing” perspective (Siegel 2007). Talking about the modes in the chairs below in the third person makes perspective changes easier. After standing up the therapist first asks the patient what he or she feels while looking at the scene below. Often the formerly blocked primary emotion pops up now. If not, the substitution technique is helpful. There are two parts of the substitution technique: 1. The Therapists asks the patient, if he or she has a good and wise friend. Then he or she is asked to step in this friend´s shoes and look at the scene. Usually a healthy adult perspective shows up and can be worked with. 2. If the patient cannot sympathize with the child modes it can be replaced by a real child the patient likes (e.g. a son or daughter or another beloved child the patient knows). Then he or she is asked what feelings come up for this kid. 6 After a “healthy adult alliance” is formed between patient and therapist there are two ways to continue: Either the therapist is modeling a healthy adult or the therapist supports the patient to be the healthy adult him- or herself (and maybe feeds the line to do so). First the parent mode has to be reappraised and “impeached”. If the therapist went ahead he asked the patient beside him how he felt watching the therapist doing so. If critical thoughts appear the therapist asks the patient, what was wrong in the things he said? This helps identifying critical parent voices. They are placed on the parent mode chair and are impeached again until the patient feels “right” in his healthy adult mode. Finally the therapists ask the patient what he feels in the body while acting so strong to consolidate this pattern in the patient´s brain. In the next step therapist and patient turn to the child chair and the therapist ask the patient, what the child needs now. In the early stages of therapy the therapist cares for the child to soothe it and then ask the patient how the child reacts and what it needs furthermore. He continues until the child is save and happy. Then he asks the patient beside him how he or she feels while watching the therapist doing so, followed by the request to soothe the child in his own words and monitoring his feelings. At the end of this sequence the patient the therapist ask the patient to be aware of his emotional state and keep it while sitting down on a new chair for the healthy adult placed between the child mode chairs and the parent mode chair. Implementing the new solution on the mode chair level In the final step of the exercise the new healthy adult perspective is fixed on the mode chair level. Therefore the therapist asks the patient to be aware how he now feels between the parent and child mode chairs and where he wants to place the parent chair. Sometimes it is sufficient to push the parent mode chair a bit back. Sometimes it is better to throw it out of the door. After the patient places the parent mode chair further away the patient takes a seat there and has to tell how the parent modes react. Then the patient has to defeat the parent mode voices again until they give up control about the situation. The power of control has to be among the healthy adult. Then the patient talks to the child and promises to take care for the child from now on. Finally he has to move to the child chair and confirm that the child is calm and safe now and trust the healthy adult. The session is closed on the healthy adult mode chair and the therapist asks the patient how he or she feels now compared to the beginning of the session and what the homework assignment for the next week could be. Summary Compared to Gestalt work this mode work model is a guided top down approach. While in Gestalt therapy the working model emerges out of the process this Mode Map is a preexisting model of the patient´s (and at least everybody´s) inner world that has to be tailored for the patient. All existing modes can be placed somewhere on the dimensional Mode Map. The model has to be introduced in the beginning of therapy and the therapist goes ahead in developing it. To adjust the model with the patient´s self concept the patient´s feedback is necessary. Therapist and patient detect and label the modes together. If the model doesn´t fit the therapist continues to explore and separate the mode states further unless the mode 7 map is consented. The Mode Map helps to explore the full spectrum of modes. Like a real map it tells patient and therapist where they are and where to go get in touch with all the modes of the patient. This leads to a sense of coherence and gives full access to the resources needed for a healthy adult behavior. E.g.: To be able to fight for your rights or protect yourself you have to be in touch with your anger power. Anger is the “gas in the tank” for fighting. On the other hand fighting must be allowed by the parent modes. Another example: A narcissistic patient has to be in touch with his vulnerable child mode and his need for attachment to accept compromises and stop dominating others. The Mode model provides the patient with a mental map that he or she can refer to in every day conflicts. Combining chairwork with a comprehensive internal working model links emotional experiencing with a cognitive representation and makes rule extraction easier. It links the best of the two worlds of emotional experiencing and cognitive processing. The healthy adult behavior of the therapist gives a model for effective problem solving. It is helpful to audiotape the sessions e.g. with a smartphone so the patients can listen to the therapist´s voice between the sessions. This helps “internalizing” the therapist as a healthy adult model and building up helpful internal dialogs outside therapy. The patients can talk to themselves in the way the therapist did in the sessions. So they get independent from therapy by building up in internal therapist working with the inner mode map world. References: Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. Damasio AR (1999). The feeling of what happens. Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace. Ekman P (1993). Facial expression and emotion. Am Psychol; 48: 384–92. Roediger, E. (2012a). Basics of a dimensional and dynamic Mode Model. Online paper: http://www.isst-online.com/sites/default/files/E.%20Roediger%20%20Basics%20of%20a%20dimensional%20and%20dynamic%20Mode%20Model-doc.pdf Roediger, E. (2012b). Why are mindfulness and acceptance central elements for therapeutic change? An integrative perspective. In: van Vreeswijk M, Broersen J, Nadort M (eds). Handbook of Schema Therapy. Theory, Research and Practice. New York: Wiley Siegel DJ (2007). The mindful brain. Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of WellBeing. New York: Norton. Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME (2003). Schema Therapy – a Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford Press. Author: Eckhard Roediger M.D, Director of the Frankfurt Schema Therapy Institute, Germany Secretary of the ISST, www.schematherapie-roediger.de, kontakt@eroediger.de 8