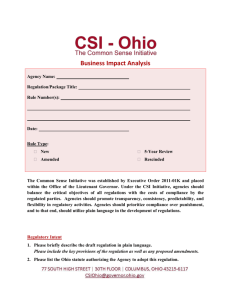

What do we mean by regulated and unregulated activities

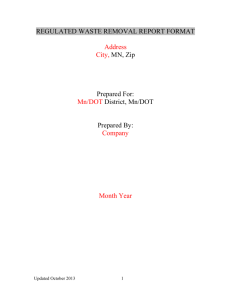

advertisement