Measuring progress in Shor`s factoring algorithm

advertisement

Measuring progress in Shor’s factoring algorithm

Thomas Lawson

Télécom ParisTech,

Paris, France

1 / 58

Shor’s factoring algorithm

What do small factoring experiments show?

Do they represent progress?

2 / 58

Overview

Picking the calculation

Shortcuts

A measure of success

3 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Shor’s factoring algorithm

4 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Factoring

To factor N

1

coprime x

2

order r, (xr mod N = 1)

3

factors are gcd(x 2 ± 1, N ).

r

N=21

3

Pick coprime x

Find order r

gcd

7

5 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Order finding

Factoring N = 21 using coprime x = 4.

The order is given by 4r mod 21 = 1.

40 = 1

41 = 4

42 = 16

43 = 64

44 = 256

45 = 1024

46 = 4096 . . . .

6 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Order finding

Factoring N = 21 using coprime x = 4.

The order is given by 4r mod 21 = 1.

40 mod 21 = 1

41 mod 21 = 4

42 mod 21 = 16

43 mod 21 = 1

44 mod 21 = 4

45 mod 21 = 16

46 mod 21 = 1

....

Here r = 3.

7 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Factoring: an example

Factoring N = 21 using coprime x = 4.

The order is given by 4r mod 21 = 1.

40 mod 21= 1

41 mod 21= 4

42 mod 21= 16

43 mod 21 = 1

44 mod 21 = 4

45 mod 21 = 16

46 mod 21 = 1

....

Here r = 3.

8 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Factoring: an example

The factors of N = 21 are

3

gcd(4 2 ± 1, 21)

= gcd(8 ± 1, 21)

= gcd(7, 21) and gcd(9, 21)

=7 and 3.

9 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Quantum order finding

Quantum operators speed it up.

U |1i = |4i

U 2 |1i = |16i

U 3 |1i = |1i

10 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Quantum order finding

U contains the whole order, r.

U |φk i = αk |φk i

U r |φk i = |φk i

αkr = 1

11 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Quantum order finding

U contains the whole order, r.

U |φk i = αk |φk i

U r |φk i = |φk i

k

αk = e2πi r

12 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Quantum order finding

The QOFA quickly finds αk .

Rn M n . . .

|100...0>

|+>

U

n

2

...

|+>

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M1

U

k

= 0.M1 M2 M3 . . . Mn

r

13 / 58

| Shor’s factoring algorithm

Quantum order finding

The output of the quantum order finding algorithm.

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

(for n → ∞).

14 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Picking the calculation

15 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

Normally the distribution becomes fuzzy as n is reduced.

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

16 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

Normally the distribution becomes fuzzy as n is reduced.

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

17 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

But for trivial calculations this does not happen.

For order

r = 4,

Pr

0/4

1/4

2/4

3/4

Output

18 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

But for trivial calculations this does not happen.

For order

r = 4,

Pr

0.000 0.010 0.100

0.110

Output

19 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

A circuit that does this

|100...0>

|+>

R3 M3

U4

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

U²

R1 M1

U

Pr

0.000 0.010 0.100

0.110

Output

20 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

A circuit that does this

|100...0>

|+>

H

0

I

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

U²

R1 M1

U

Pr

0.000 0.010 0.100

0.110

Output

21 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

A circuit that does this

|100...0>

|+>

H

0

I

I

R2 0/1

I

U²

R1 0/1

U

Pr

0.000 0.010 0.100

0.110

Output

22 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Trivial calculations

This happens if r = 2p ,

because 1/r represented in binary.

N = 15 gives r = 2 or r = 4. This is always trivial.

23 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Nontrivial calculations

Nontrivial: N = 21 with x = 4 gives r = 3.

1

= 0.01010101 . . .

3

24 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Nontrivial calculations

a"

⇥0

⇥0

⇥0

⇥0

⇥0

⇥1

⇥0

H"

H"

2

c"

{I,R}" H"

H"

(n;1)"

Further"iteraBons"

to..."

(n;2)"

U"2" N = 21 with x U"

Factoring

=2" 4 (giving r = 3).

3

8

Probability"

b"

0

0

0

1

0

00

01

10

11

U"2

n=2"

U"

0.35

0.35

1

4

1

8

1

2

0"

U"2"

000

011

101

0

0000

0101

1011

Increasing"precision"

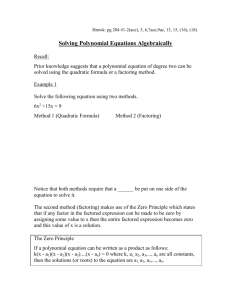

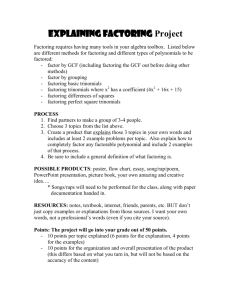

FIG. 1: The iterative order finding algorithm for factoring 21. a, Measurement of the control qubit after each controlled

unitary gives the next most significant bit in the output and the outcome is fed forward to the iterated (semi-classical) Fourier

transform, which applies either the identity operation I or the appropriate phase gate R, prior to the Hadamard H. b, As

the number of iterations increases the precision increases. c, For two bits of precision the controlled unitary operations can be

constructed with this arrangement of controlled-swap gates.

Fourier transform is constructive for states contributing

to the 00 term and boosts its probability of observation

to three times that of the probability for observing the

10 term, which experiences destructive quantum interference among its contributory states. Decoherence in the

two qubit control register, the single swap of U 2 is implemented with a controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate; U 1 is

realised with two swaps, the first of which is a CNOT

gate, while it is sufficient for the second swap to be un25 / 58

controlled. (See Appendix for details).

| Picking the calculation

Second cause of triviality

Lack of precision.

|100...0>

|+>

R3 M3

|+>

U4

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M1

U

If r > 2n no interference happens.

26 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Second cause of triviality

Lack of precision.

R3 M3

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

R1 M1

|100...0>

|+>

If r > 2n no interference happens.

27 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Second cause of triviality

For n steps, only 2n states can be accessed.

R3 M3

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

R1 M1

|100...0>

|+>

If r > 2n no interference happens.

28 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Second cause of triviality

Lack of precision.

R3 M3

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

R1 M1

|100...0>

|+>

If r > 2n no interference happens.

29 / 58

| Picking the calculation

Idée reçue 1)

Short r are easy.

In fact

r = 212 is easier than r = 3,

r must be small.

30 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Experimental shortcuts

31 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Simplifying the circuit

Demonstrations use shortcuts:

Compiling

Circuit simplifications

Substitutions

32 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Compiling

Compiling removes the hardest part of the algorithm - making the unitary

n

operators, U 2 .

Rn M n . . .

|100...0>

|+>

U

n

2

...

|+>

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M1

U

33 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Compiling

7

Rn M n . . .

|100...0>

|+>

U

n

2

...

|+>

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M1

U

Figure: Niskanen et al. 2004.

34 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Compiling

All demonstrations have used compiling.

Rn M n . . .

|100...0>

|+>

U

n

2

...

|+>

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M1

U

It is not scalable.

It needs knowledge of the calculation.

A part of the algorithm is missing.

35 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Compiling

All demonstrations have used compiling.

Rn M n . . .

|100...0>

|+>

U

n

2

...

|+>

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M1

U

It is not scalable.

It needs knowledge of the calculation.

A part of the algorithm is missing.

36 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Simplifying the circuit

Demonstrations use shortcuts:

Compiling

Circuit simplifications

Substitutions

37 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Circuit simplifications

Unused qubits are removed.

R3 M3

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

R1 M1

|100...0>

|+>

This is fine (even if it needs knowledge of the calculation).

38 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Circuit simplifications

Unused qubits are removed.

R3 M3

|+>

R2 M2

|+>

R1 M1

|100...0>

|+>

This is fine (even if it needs knowledge of the calculation).

39 / 58

A<< 9D89 O:HF9 , FA F7 '.!C 87B O:HF9A - 87B W 8;< F7 8 ?FN9:;< >K '.! 87B

',!6 #D< ;<EFA9<; FA 9D:A F7 8 ?FN9:;< >K '...!C '.,.!C ',..! 87B ',,.!C >;

'.!C '-!C '+! 87B ']!6 #D< @<;F>BF=F9Q F7 9D< 8?@JF9:B< >K '%! FA 7>5 -C A>

" ! L!- ! + 87B E"="B""0+!- ! ,# ,\# ! W# \6 #D:AC <G<7 8K9<; 9D< J>7E

87B =>?@J<N @:JA< A<O:<7=< >K 9D< BFKM=:J9 =8A< RPFE6 +SC 9D<

B898 =>7=J:AFG<JQ F7BF=89< 9D< A:==<AAK:J <N<=:9F>7

Doing otherwise<N@<;F?<798J

is a waste

of resources.

>K VD>;UA 8JE>;F9D? 9> K8=9>; ,\6

!<G<;9D<J<AAC

Factor N = 15 giving

r =9D<;<

4. 8;< >HGF>:A BFA=;<@87=F<A H<95<<7 9D< ?<8AI

:;<B 87B FB<8J A@<=9;8C ?>A9 7>98HJQ K>; 9D< BFKM=:J9 =8A<6 $AF7E 8

7:?<;F=8J ?>B<JC 5< D8G< F7G<A9FE89<B 5D<9D<; 9D<A< B<GF89F>7A

| Experimental shortcuts

Circuit simplifications

|100...0>

|+>

H

a

(0)I

n

m

!0"

|+>

0

(1)

H

R2 M2

(2) U²

n

!1"

|+>

x

1

ax mod N

U (4)

Inverse

QFT

b

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

T

e

m

p

o

r

a

l

a

v

e

r

a

g

i

n

g

H

H

90 H

H

5F9D $ ! , # -#.!( , C , !

K>JJ>5F7E >HA<;G89F>7A

AF7EJ< A@F7 B<A=;F@9F>7A

R,S b"1 R87B c1S <

=>??:9<T R-S 9D< *) K>;

8@@JF<B 9> 8;HF9;8;Q "T 87

R1 M1

(3)

x

87B @D8A< B8?@F7E Rc1

"!!!) ,

*. ! %

.

i

ω i /2π

T1,i

T2,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

–22052.0

489.5

25088.3

–4918.7

15186.6

–4519.1

4244.3

5.0

13.7

3.0

10.0

2.8

45.4

31.6

1.3

1.8

2.5

1.7

1.8

2.0

2.0

45 90 H

H

A B

C

D

E

F

G

H

!"#$%& ' !"#$%"& '()'"(% *+) ,-+)./ #01+)(%-&2 (3 4"%0($5 +* %-5 6"#$%"& '()'"(%2 7()5/

)58)5/5$% 6"9(%/3

#$: 9+;5/ )58)5/5$%

+85)#%(+$/2 <(&5

05*% %+ )(1-%2 =>? @$(%(#0(A5

Figure:

Vandersypen

et1+5/

al.*)+&2001.

# B)/% )51(/%5) +* ! ! C"0+1C "# 6"9(%/ %+ %>! ! ! ! %>! =*+) /-+)% D>!? #$: # /5'+$:

!"#$%& * ,%)"'%")5 #$: 8)+85)%

85)X"+)+9"%#:(5$G0 ()+$ '+&805

&5#/")5: / ELU EON K#0"5/3 J5 '+

:(**5)5$% *)+& %-#% :5)(K5: ($ )5*2

=($ HA? #% EE2T <3 )50#%(K5 %+ # )5

EL

40 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Simplifying the circuit

Demonstrations use shortcuts:

Compiling

Circuit simplifications

Substitutions

41 / 58

| Experimental shortcuts

Substitutions

Technology which is not ready is replaced.

R2 M2

U²

|+>

R1 M 1

U

The global properties can be tested.

42 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Testing Shor’s algorithm

43 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Idée reçue 2)

The number factored is a good measure.

15 4

21 4

51

85

This does not represent progress.

44 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Idée reçue 2)

The number factored is a good measure.

15 4

21 4

51

85

This does not represent progress.

45 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Idée reçue 3)

Factoring (like love) should be blind.

Avoid trivial cases.

Factoring is physics.

46 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Idée reçue 4)

Factoring a large number is a good test.

3 × 7 = 21

This shows the computer works. But it doesn’t say how well.

47 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Idée reçue 4)

Factoring a large number is a good test.

3 × 7 = 21

Bad circuits occasionally get the factors

Perfect circuits often fail

48 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

A test of progress

We should test the order finding algorithm.

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

49 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

A test of progress

The overlap improves with n.

|+>

R M |+>

U128

R M |+>

U64

R M |+>

U32

R M |+>

U16

R M |+>

U8

R M |+>

R M |+>

U2

U4

R M

U

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

50 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

A test of progress

The overlap improves with n.

|+>

R M |+>

U128

R M |+>

U64

R M |+>

U32

R M |+>

U16

R M |+>

U8

R M |+>

R M |+>

U2

U4

R M

U

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

51 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

A test of progress

The overlap improves with n.

|+>

R M |+>

U128

R M |+>

U64

R M |+>

U32

R M |+>

U16

R M |+>

U8

R M |+>

R M |+>

U2

U4

R M

U

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

52 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

A test of progress

The overlap improves with n.

|+>

R M |+>

U128

R M |+>

U64

R M |+>

U32

R M |+>

U16

R M |+>

U8

R M |+>

R M |+>

U2

U4

R M

U

Pr

...

1/r

2/r

3/r

4/r

5/r

Output

53 / 58

| Testing Shor’s algorithm

Conclusion

To design a factoring experiment

1

choose a nontrivial case,

2

only leave out uninteresting parts of the circuit,

3

judge the quantum order finding algorithm.

54 / 58

| Thank you for your attention.

Thank you for your attention.

55 / 58

| Extras

Extras

56 / 58

| Extras

QFT vs iterative PEA

a)

#" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " #

#

H

...

|0!

H

#

H

#

•

|0!

..

.

#

#

#

|0!

...

#

H

•

...

#

•

#

•

...

Rn−1

R1

•

H

•

!!!

# ..!"

# .

#

!!!

# !"

#

!!!

# !"

#

Rn

...

R1

H

#

#

#

#

...

2

U

U2

#

# U

" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "

|1!

n

b)

|0!

|1!

H

•

U2

H

n

!!!

!"

. . . |0!

...

H

φ

φ1

Rn−1

. . . R1 n−2

•

U2

H

!!!

!"

|0!

H

φ

Rnφ1 . . . R1 n−1

•

H

!!!

!"

U

57 / 58

| Extras

Odd r

The factors are

r

gcd(x 2 ± 1, N )

N = 21, x = 4 gives r = 3

3

gcd(4 2 ± 1, 21)

= gcd(23 ± 1, 21)

since x is a perfect square.

58 / 58