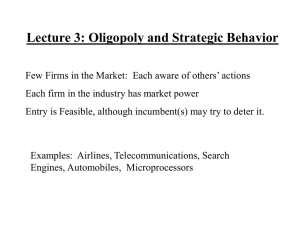

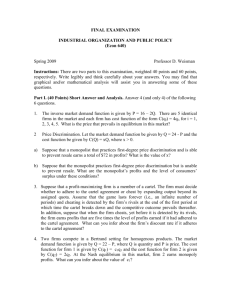

Industrial Combination

advertisement