Management Planning for Natural World Heritage Properties

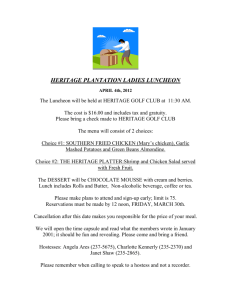

advertisement