TRAIT-FACTOR COUNSELING/PERSON x ENVIRONMENT FIT

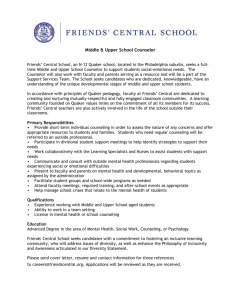

advertisement