Percentage of Tumor and Tumor Length in Prostate Biopsy

advertisement

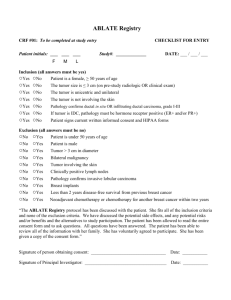

Anatomic Pathology / Tumor Percentage in Prostate Cancer Percentage of Tumor and Tumor Length in Prostate Biopsy Specimens A Study of American Veterans Robin T. Vollmer, MD Key Words: Prostate cancer; Tumor percentage; Tumor length; Survival; Grade; Needle biopsies; Serum PSA; Tumor size; Age DOI: 10.1309/AJCP3VUXBYTEY3PU In this study, the tumors of 451 Veterans Affairs patients with prostate cancer were examined. In the biopsy specimens, percentage of tumor and tumor length were observed in addition to Gleason grade. The patients were then followed up until death or for a mean of 4.9 years to see how these measures of the quantity of tumor in the biopsy specimens related to overall survival. Cox proportional hazards model analysis demonstrated that patient age and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level were related significantly to overall survival. After controlling for these 2 variables, percentage of tumor was significantly related to overall survival (P = .0012), and after controlling for age and PSA level, tumor length was significantly related to overall survival (P = .00026). Nevertheless, these 2 measures did not add prognostic information, that is, either one or the other was significant, but not both, probably because they are closely correlated. The results favor including one or the other of these 2 quantitative measures in reports on prostate biopsy specimens with tumor. 940 940 Am J Clin Pathol 2008;130:940-943 DOI: 10.1309/AJCP3VUXBYTEY3PU For any biopsy of the prostate, the most important issue for the patient and his pathologist is the presence of cancer. Once cancer is found, the patient’s concerns turn to whether he will die prematurely, whether the tumor will make him suffer, and what, if any, treatments he should seek. Once the cancer is found, the pathologist’s concerns turn to issues of histologic grade and quantity of tumor. It is therefore no coincidence that the pathologist’s secondary concerns address, at least partly, the secondary concerns of the patient. For example, the Gleason grading scheme was formulated because it related significantly to overall survival.1 In addition, many have shown that the combination of histologic grade and measures of tumor quantity in the initial biopsy specimen relate to outcomes in prostate cancer (see Vollmer2 for a list of references). However, and in contrast with Gleason’s initial study of histologic grading, recent studies have favored outcomes other than overall survival, including tumor stage and tumor volume. Perhaps the most popular outcome to study has been biochemical failure,3 an outcome that is difficult to define and one that is loosely connected to firmer outcomes such as distant metastases and overall survival.4-7 Thus, to more directly address patients’ concerns about premature death, I have favored the outcome of overall survival, and it is reasonable to assume that any tumor factors related to overall survival time should be helpful for deciding whether to treat or which treatments to use. Whereas most have accepted the Gleason grading scheme, including the International Society of Urological Pathology consensus revision,8 as optimal for grading prostate cancer, there is less consensus on how to measure the amount of tumor in the biopsy specimens. Methods of measurement include the number of positive cores, fraction of positive cores, percentage of © American Society for Clinical Pathology Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 1, 2016 Abstract Anatomic Pathology / Original Article tissue with tumor, and tumor length in millimeters. Recently, I found that total tumor length provided more information about overall survival than the Gleason score or the fraction of positive cores.2 Herein, I report the examination of the relative prognostic importance of percentage of tumor and total tumor length in 451 Veterans Affairs patients with prostate cancer and a mean of more than 4 years’ follow-up. Materials and Methods Study Patients © American Society for Clinical Pathology Statistical Methods To relate clinical and histologic variables to overall survival time, I used Kaplan-Meier plots and the Cox proportional hazards model.9 To relate the percentage of tumor to tumor length, I used linear regression. All analyses were done using S-PLUS software (MathSoft, Seattle, WA), and all P values are 2-sided. Results Survival and Percentage of Tumor in Biopsy Specimens zFigure 1z shows the distribution of percentage of tumor in the study population, and it demonstrates an exponential distribution much like that of tumor length.2 For 49% of the cases, the percentage of tumor was less than 5%; 14% of the cases had a percentage of tumor between 5% and 10%; 17% of cases were between 10% and 20%, 5% between 20% and 30%, 7% between 30% and 40%, 2% between 40% and 50%, and just 6% of cases were more than 50% of tumor. Thus, most men with prostate cancer in this study had a limited amount of tumor. zFigure 2z shows a Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of survival at last follow-up vs the percentage of tumor in the needle biopsy specimens of the prostate. The plot demonstrates that biopsy specimens with higher percentages of tumor were associated with a lower probability of survival, and a univariate Cox model analysis demonstrated that this zTable 1z Characteristics of the Study Population Characteristic Result No. of patients Mean (range) age (y) Primary treatment Surgery Radiation Other Mean (range) of serum prostate-specific antigen (ng/mL)* Mean (range) of total number of biopsy cores Mean (range) of biopsy Gleason score No. of deaths Mean (range) follow-up in patients alive at last follow-up (y) Mean (range) percentage of tumor in biopsy specimens * 451 63 (42-87) 310 105 36 10.6 (0.1-99.2) 8.3 (2-16) 6.6 (5-10) 52 4.9 (0.5-15.2) 14.4 (0.1-90) Units given are conventional; to convert to Système International units (µg/L), multiply by 1.0. 941 Am J Clin Pathol 2008;130:940-943 DOI: 10.1309/AJCP3VUXBYTEY3PU 941 941 Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 1, 2016 The study patients comprised 451 men whose prostate cancer was diagnosed by needle biopsy. All of the diagnoses were made by me, and, in addition, I prospectively recorded the Gleason score, the number of cores with tumor, the total tumor length in millimeters,2 and an estimate of the percentage of tissue with tumor. Specifically, the percentage of tumor present was estimated as the fraction of all tissue occupied by tumor multiplied by 100, and this estimate was obtained subjectively, that is, without formal measurements or reliance on tumor length. Nevertheless, if tumor was present in several separate slides (blocks), the percentage of tumor in each slide was estimated separately, summed, and then finally divided by the total number of slides (blocks) to achieve an overall average. Tumor length comprised the total tumor length in millimeters for all core biopsy specimens containing tumor and was measured as before.2 Two foci of tumor in a single set of cores were measured separately if they were separated by lobules of benign glands or by gland-free expanses of benign stroma, and this decision was made subjectively, relying on my experience with evaluating previous prostatectomy specimens. All of the men were patients in the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC). Of the 451 patients, 310 were treated with radical prostatectomy, 105 primarily by external beam radiation therapy, and 36 as needed by other methods, including hormonal therapy. In general, information about clinical stage was not uniformly documented in their medical records; however, I assumed that all patients treated by surgery or radiation therapy had clinically localized tumor, because the standard of practice routinely excluded these treatments for patients with evidence of metastatic tumor. The only inclusion criteria for the study were the diagnosis of prostate cancer, a measurement of tumor length, and an estimate of the percentage of tumor. (Gleason grade was present in all the cases.) The only exclusion criterion for the study was a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level exceeding 100 ng/mL (100 µg/L), because I judged that when such high values of PSA were present, the amount of tumor in the needle biopsy specimens would be considered of minor importance. Thus, all 451 men in this study had initial values of PSA less than 100 ng/mL (100 µg/L). I obtained survival data from hospital records or public records of deaths, and the study was approved by the local VAMC Institutional Review Board. Other details about these study patients and their tumors are given in zTable 1z. Vollmer / Tumor Percentage in Prostate Cancer 1.0 Survival Probability 250 No. of Cases 200 150 100 50 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 0 0 20 40 60 0 80 20 40 Discussion Although many older men get cancer of the prostate, just a fraction of them die of this tumor. Thus, the diagnosis of prostate cancer does not by itself imply shortened survival 942 942 Am J Clin Pathol 2008;130:940-943 DOI: 10.1309/AJCP3VUXBYTEY3PU zTable 2z Two Cox Model Analyses* Variable Coefficient Model with percentage of tumor (LR = 32) Patient age Serum PSA level Percentage of tumor Model with tumor length (LR = 33) Patient age Serum PSA level Tumor length 0.0552 0.427 0.0190 0.0501 0.451 0.0199 P .011 .022 .0012 .020 .013 .00026 LR, likelihood ratio of the model; PSA, prostate-specific antigen. * Coefficients are given for just the significant variables in 3-variable models. The serum PSA level was used with a natural logarithm transformation; and age, percentage of tumor, and total tumor length were coded as continuous variables. The LR provides a measure of how well the model fit the survival results. 80 60 40 20 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Square Root of Tumor Length zFigure 3z Plot of the percentage of tumor vs the square root of tumor length. The square root transformation was used to demonstrate a nearly linear relationship and to obtain approximate normality to the residuals for the accompanying linear regression analysis. © American Society for Clinical Pathology Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 1, 2016 association was significant (P = 4.2 × 10–6). Nevertheless, univariate Cox model analyses also demonstrated that patient age (P = .0008), serum PSA level (P = 7 × 10–7), and tumor length (P = 6 × 10–8) were significantly associated with survival. The biopsy Gleason score, coded as 6 or less vs 7 vs more than 7, was of borderline significance (P = .048). zTable 2z shows 2 Cox model analyses, the first using the percentage of tumor as the measure of tumor quantity and the second using tumor length. Both models demonstrate that the quantity of tumor was significantly related to overall survival after controlling for the effects of patient age and serum PSA level. With the presence of age, serum PSA level, and quantity of tumor present as explanatory variables, Gleason score (coded as described) provided no additional prognostic information (P > .7). The model likelihood ratios provide a measure of how well the Cox models fit the survival data. Because both models had similar likelihood ratios, because both models had similar coefficients for patient age and serum PSA level, and because both measures of quantity of tumor had P values of similar magnitude, the results suggest that tumor length, as a prognostic variable, provides no more than a modest advantage over percentage of tumor. Furthermore, using both variables together provided no significant additive information (P > .1). These results suggest that the percentage of tumor and tumor length were closely related to one another, and this is demonstrated in zFigure 3z, which is a plot of percentage of tumor vs the square root of tumor length. The scatter plot shows a strong positive association between percentage of tumor and tumor length (P ~ 0 by linear regression). 80 zFigure 2z Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of survival at last follow-up vs the percentage of tumor in biopsy specimens of the prostate. The faint upper and lower lines give 95% confidence intervals. Percent Tumor zFigure 1z Percentage of tumor in biopsy specimens of the prostate. 60 Percent Tumor Percent Tumor Anatomic Pathology / Original Article © American Society for Clinical Pathology Regardless, this preliminary study shows once again that the quantity of tumor in needle biopsy specimens relates to overall survival. Thus, prospective studies of outcomes for prostate cancer and studies designed to select and test new molecular genetic markers for prostate cancer should include an estimate of the overall percentage of tumor present or total tumor length. Otherwise, one risks identifying an expensive marker for outcomes only to discover later that it is no better a prognosticator than the quick and cheaply obtained estimate of percentage of tumor. Because I have not been able to demonstrate superiority of one measure over the other, some may, for the moment, want to include both measures in their data. Finally, I recommend that pathologists routinely include in their reports of positive biopsy specimens an estimate of the overall percentage of tissue replaced by tumor. From Laboratory Medicine, Veterans Affairs and Duke University Medical Centers, Durham, NC. Address reprint requests to Dr Vollmer: Laboratory Medicine 113, VA Medical Center, 508 Fulton St, Durham, NC 27705. References 1. Gleason DF. Histologic grading and clinical staging of prostatic carcinoma. In: Tannenbaum M, ed. Urologic Pathology: The Prostate. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1977:171-198. 2. Vollmer RT. Tumor length in prostate cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:77-82. 3. Cookson MS, Aus G, Burnett AL, et al. Variation in the definition of biochemical recurrence in patients treated for localized prostate cancer: The American Urological Association prostate guidelines for localized prostate cancer update panel report and recommendations for a standard in the reporting of surgical outcomes. J Urol. 2007;177:540-545. 4. Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999;281:1591-1597. 5. Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, et al. Risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294:433-439. 6. Thames H, Kuban D, Levy L, et al. Comparison of alternative biochemical failure definitions based on clinical outcome in 4839 prostate cancer patients treated by external beam radiotherapy between 1986 and 1995. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 2003;57:929-943. 7. Vollmer RT, Montana GS. The dynamics of prostate-specific antigen after definitive radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4119-4125. 8. Epstein JL, Allsbrook WC Jr, Amin MB, et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;9:1228-1242. 9. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. 943 Am J Clin Pathol 2008;130:940-943 DOI: 10.1309/AJCP3VUXBYTEY3PU 943 943 Downloaded from http://ajcp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 1, 2016 time. This study, like its predecessor,2 demonstrates that men who die prematurely after the diagnosis of prostate cancer have a greater quantity of tumor in the needle biopsy specimens. In fact, the quantity of tumor as measured by percentage of tumor present or total tumor length provides stronger prognostic information about overall survival than does patient age, serum PSA level, or Gleason score. The fraction of men who have more than 30% of the tissues in a biopsy specimen replaced by tumor or who have greater than 20 mm of tumor length tend to die sooner, but fortunately, as Figure 1 demonstrates, this is a small fraction. This study, however, does not demonstrate which of these 2 measures of tumor quantity is better than the other, and it demonstrates that the 2 measures are closely related to one another. The percentage of tumor is easier and quicker to estimate than total tumor length, and it requires neither a calibrated eyepiece micrometer nor elaborate measurements. If one evaluates each slide with tumor independently, as I have done in this study, then estimating the percentage of tumor on the slide is relatively easy. Sometimes, it helps to proceed stepwise through a mental algorithm. On a given slide with tumor, first consider if the percentage of tumor constitutes less than or more than 50% of the tissue. If it is less than 50% (as most are), is it less than or more than 25%? Then by proceeding in such a stepwise manner, I have been able to comfortably narrow the estimate of tumor on a single slide to within 5% to 10% increments. After including 0% estimates for the slides without tumor, one simply averages these estimates over all of the slides. I have also informally observed that pathology residents can obtain close consensus estimates of the percentage of tumor present. On the other hand, estimating the percentage of tumor is clearly a more subjective process than measuring total tumor length with an eyepiece micrometer. Furthermore, it is possible that some of the significance of the association between percentage of tumor and overall survival in this study was due to my being the only observer. In other words, the percentage of tumor could suffer as a prognostic variable in comparison with total tumor length if it were to be recorded by different pathologists, because the variance in the process would increase. Although formal interobserver studies regarding tumor length and percentage of tumor are needed to address such issues, I have not studied this, because I was the only full-time surgical pathologist at the VAMC during this prospective study. In addition, because the mean follow-up in censored patients in the present was just 4.9 years, it is possible that longer follow-up and more observed deaths could demonstrate greater importance for the Gleason score and for showing which of these 2 methods for measuring the amount of tumor is better.