Kant, Morality and Religion 2

advertisement

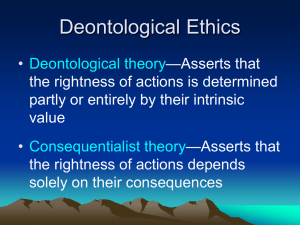

Copleston Morality and Religion I. Kant’s Aim A. Moral Knowledge: not knowledge of what is, that is of how men actually behave, but of what ought to be, that is to say, of how men ought to behave (308) 1. A priori in that it does not depend on men’s actual behavior – true independently of the conduct of men (308) 2. “For Kant the primary task of the moral philosopher should be that of isolating the a priori elements in our moral knowledge and showing their origin. In this sense we can depict the moral philosopher as asking how the synthetic a priori propositions of morals are possible” (309) 3. “Our moral knowledge taken as a whole contains a variety of elements; and it is the primary task, though not the only possible task, of the moral philosopher to lay bare the a priori element, freeing it from all empirically derived elements, and to show its origin in the practical reason.” (309) B. Practical Reason: reason in its practical (moral) function 1. “In the final analysis there can only be one and the same reason which is to be differentiated solely in its application.” (GMM, 391) 2. “Though ultimately one, reason can be concerned with its object in two ways. It can determine the object, the latter being originally given from some other source than reason itself. Or it can make the object real” (310-311) 3. “The first is theoretical, the second practical rational knowledge.” (B x) 4. “In its theoretical function reason determines or constitutes the object given in intuition…It applies itself, as it were, to a datum given from another source than reason itself. In its practical function, however, reason is the source of its objects; it is concerned with moral choice, not with applying categories to the data sense intuition.” (310) 5. “Theoretical reason is directed towards knowledge, while practical reason is directed towards choice in accordance with moral law and, when physically possible, to the implementation of choice in action. 6. “For Kant the moral philosopher must find in the practical reason the source of the a priori element in the moral judgment.” (310) a. “[This] statement implies that there is an a posteriori element, which is given empirically…We can distinguish between the concept of moral obligation as such and the empirically given conditions of this particular duty.” (311) b. “Further, when Kant speaks of the practical reason or rational will as the fount of the moral law, he is thinking of practical reason as such, not of the practical reason as found in a specific class of finite beings, that is, in human beings. True, he does not intend to state that there are finite rational beings other than men. But he is concerned with the moral imperative as bearing on all beings which are capable of being subject to obligation, whether they are men or not. Hence, he is concerned with the moral imperative regarded as antecedent to consideration of human nature and its empirical conditions.”1 1 311 c. “And if practical reason is looked on in this extremely abstract way, it follows that moral laws, in so far as they make sense only on the supposition that there are human beings, cannot be deduced from the concept of practical reason. For instance, it would be absurd to think of the commandment ‘Thou shall not commit adultery’ applying to pure spirits, for it presupposes bodies and the institution of marriage.”2 d. “We have to distinguish between pure ethics or the metaphysics or morals, which deals with the supreme principle or principles of morality and with the nature of moral obligation as such, and applied ethics, which applies the supreme principle or principles to the conditions of human nature.”3 7. “According to Kant, there is need for a metaphysics of morals which will prescind from all empirical factors.”4 8. Kant’s main point: “The ground of obligation here must there be sought not in the nature of man nor in the circumstances of the world in which man is placed, but must be sought a priori solely in the concepts of pure reason; he must grant that every other precept which is founded on principles of mere experience – even a precept that may in certain respects be universal insofar as it rests in the least on empirical grounds, perhaps only in its motive – can indeed be called a practical rule, but never a moral law.”5 a. A pure ethics must be worked out which, “When applied to man, it does not in the least borrow from acquaintance with him (anthropology) but gives a priori laws to him as a rational being.”6 b. Kant wants to find within reason itself the “basis of the a priori element in the moral judgment, the element which makes possible the synthetic a priori propositions of morals.”7 c. He is searching for the “ultimate source of the principles of the moral law in reason considered in itself, without reference to specifically human conditions.”8 d. “Kant rejects empiricism and must be classed as a rationalist in ethics, provided that this word is not taken to mean someone who thinks that the whole moral law is deducible by mere analysis from some fundamental concept.”9 9. For Kant, “belief in God is grounded in the moral consciousness rather than the moral law on belief in God.”10 II. The Good Will A. “There is no possibility of thinking of anything at all in the world, or even out of it, which can be regarded as good without qualifications, except a good will.”11 1. A good will is good without qualification; it cannot be bad in any circumstances 2. E.g. wealth can be misused, courage can be misused, etc. 2 Copleston, 311. Copleston, 311. 4 Copleston, 312. 5 GMM, 389. 6 GMM, 389. 7 Copleston, 312-313. 8 Copleston, 313. 9 Copleston, 313. 10 Copleston, 313. 11 GMM, 393. 3 3. “A good will is good itself and not merely in relation to something else.”12 4. “The Kantian concept of a good will is the concept of a will which is always good in itself by virtue of its intrinsic value, and not simply in relation to the production of some end, for example, happiness.”13 5. “According to Kant, a will cannot be said to be good in itself simply because it causes, for instance, good actions.”14 B. “To elucidate the meaning of the term ‘good’ when applied to the will, Kant turns his attention to the concept of duty which is for him the salient feature of the moral consciousness. A will which acts for the sake of duty is a good will.”15 1. Can’t say that “a good will is a will which acts for the sake of duty” III. Duty and Inclination A. Must distinguish between “actions which are in accordance with duty and acts which are done for the sake of duty.”16 1. The former is wider 2. Only latter have moral worth. 3. Kant does not explicitly say that it is morally wrong to act according to one’s inclinations17 4. An action can be in accordance with duty, but such an action has no moral value B. Kant gives the impression “that in his opinion, the moral value of an action performed for the sake of duty is increased in proportion to a decrease in inclination to perform the action. In other words…in his view, the less inclination we have to do our duty, the greater is the moral value of our action if we actually perform what it is our duty to do.”18 1. “It seems to follow that the baser a man’s inclinations are, the higher is his moral value, provided that he overcomes his evil tendencies 2. However, “His main point is simply that when a man performs his duty contrary to his inclinations, the fact that he acts for the sake of duty and not simply out of inclinations is clearer than it would be if he had a natural attraction to the action.”19 a. Regardless, Kant is still maintaining that inclinations have no value in an ethical system except to act as a measuring stick. The empirical world holds no value in Kant’s ethical system. 3. For Kant, “the action of doing good to others has no moral worth if it is simply the effect of a natural inclination…but he does not say that there is anything wrong or undesirable in possessing such a temperament.”20 IV. Duty and Law A. “Duty is necessity of an action done out of respect for the law.”21 12 Copleston, 315. Copleston, 315. 14 Copleston, 315. 15 Copleston, 315. 16 Copleston, 316. 17 Copleston, 316. 18 Copleston, 316-317 19 Copleston, 317. 20 Copleston, 317. 21 GMM, 400. 13 1. Law means law as such 2. “The essential characteristic (the form, we may say) of law as such is universality; that is to say, strict universality which does not admit of exceptions.”22 3. “Physical laws are universal; and so is the moral law. But whereas all physical things, including man as a purely physical thing, conform unconsciously and necessarily to physical law, rational beings, and they alone, are capable of acting in accordance with the idea of law.”23 4. Kant distinguishes between principles and maxims (318) V. The Categorical Imperative A. Kant rejects any type of hypothetical imperative – whether problematic or assertoric – “as qualifying for the title of moral imperative”24 1. “The moral imperative must be categorical. That is to say, it must command actions, not as means to any end, but as good in themselves.”25 2. What we can purely a priori say about this categorical imperative is that it commands “that the maxims which serve as our principles of volition should conform to universal law.”26 3. “Kant’s general notion is that the practical or moral law as such is strictly universal.”27 VI. The Rational Being as an End in Itself A. “The question arises whether it is a practically necessary law (that is, a law imposing obligation) for all rational beings that they should always judge their actions by maxims which they can will to be universal.”28 2. “If this is actually the case, there must be a synthetic a priori connection between the concept of the will of a rational being as such and the categorical imperative.”29 3. Why should rational beings judge their actions by maxims which they can will to be universal laws? Because rational beings are ends in themselves. B. “[Kant] argues that that which serves the will as the objective ground of its selfdetermination is the end…this end cannot be a relative end, fixed by desire; for such ends give rise only to hypothetical imperatives. It must be, therefore, an end in itself, possessing absolute, and not merely relative, value. 1. “Kant postulates that man, and indeed any rational being, is an end in itself. The concept of a rational being as an end in itself can therefore serve as the ground for a supreme practically principle or law. 2. “The ground of this principle is this: rational nature exists as an end in itself…The practical imperative will thus be as follows. So act as to treat humanity, whether in 22 Copleston, 318. Copleston, 318. 24 Copleston, 323. 25 Copleston, 323. 26 Copleston, 323. 27 Copleston, 324. 28 Copleston, 327. 29 Copleston, 327. 23 your own person or in that of any other, always at the same time as an end and never merely as a means.”30 a. A rational being must never be used as a mere means, “as though he had no value in himself except as a means to my subjective end.” VII. The Autonomy of the Will A. “The will of man considered as a rational being must be regarded as the source of the law which he recognizes as universally binding. This is the principle of the autonomy, as contrasted with the heteronomy, of the will.”31 2. “All imperatives which are conditioned by desire or inclination or, as Kant puts it, by ‘interest’ are hypothetical imperatives. A categorical imperative, therefore, must be unconditioned. And the moral will, which obeys the categorical imperative, must not be determined by interest. That is to say, it must not be heteronomous, at the mercy, as it were, of desires and inclinations which form part of a causally determined series. It must, therefore, be autonomous. And to say that a moral will is autonomous is to say that it gives itself the law which it obeys.”32 B. “Kant speaks of the will as ‘the supreme principle of morality’ (GMM, 440) and as ‘the sole principle of all moral laws and of the corresponding duties.’ Heteronomy of the will, on the other hand, is ‘the source of all spurious principles of morality.”33 1. “If we accept the heteronomy of the will, we accept the assumption that the will is subject to moral laws which are not the result of its own legislation as a rational will.”34 2. see page 330 3. “The concept of the autonomy of the morally legislating will makes no sense unless we make a distinction in man between man considered purely as a rational being, a moral will, and man as a creature who is also subject to desires and inclinations which may conflict with the dictates of reason. And this is, of course, what Kant presupposes. The will or practical reason, considered as such, legislates, and man, considered as being subject to a diversity of desires, impulses and inclinations, ought to obey.”35 VIII. The Kingdom of Ends A. “The idea of rational beings as ends in themselves, coupled with that of the rational will or practical reason as morally legislating, brings us to the concept of a kingdom of ends.”36 2. Man belongs to this kingdom in either of two ways. “He belongs to it as a member when, although giving laws, he is also subject to them. He belongs to it as a sovereign or supreme head when, while legislating, he is not subject to the will of any other.”37 30 GMM, 429. Copleston, 329. 32 Copleston, 329. 33 Copleston, 329. 34 Copleston, 329. 35 Copleston, 330. 36 Copleston, 331. 37 Copleston, 331. 31 3. “Kant goes on to say that a rational being can occupy the place of supreme head “only if he is a completely independent being without needs and with unlimited power adequate to his will.”38 A. “This kingdom of ends is to be thought according to an analogy with the kingdom of Nature, the self-imposed rules of the former being analogous to the causal laws of the latter.”39 IX. 38 Freedom as the Condition of the Possibility of the Categorical Imperative A. “Now, the categorical imperative states that all rational beings…ought to act only on those maxims which they can at the same time, will, without contradiction, to be universal laws. The imperative thus states an obligation. But it is, according to Kant, a synthetic a priori proposition."40 2. “On the one hand, the obligation cannot be obtained by mere analysis of the concept of a rational will. And the categorical imperative is thus not an analytic proposition” 3. “On the other hand, the predicate must be connected necessarily with the subject. For the categorical imperative, unlike a hypothetical imperative, is unconditioned and necessarily binds or obliges the will to act in a certain way.” 4. “It is, indeed, a practical synthetic a priori proposition…it does not extend our theoretical knowledge of objects…It is directed towards action, towards the performance of actions good in themselves, not towards our knowledge of empirical reality”41 A. How are such propositions possible? What is the ‘third term’ that makes possible a necessary connection between predicate and subject? 5. “This ‘third term’ cannot be anything in the sensible world. We cannot establish the possibility of a categorical imperative to refer to anything in the causal series of phenomena. Physical necessity would give us heteronomy, whereas we are looking for that which makes possible the principle of autonomy. And Kant finds it in the idea of freedom.”42 6. “Obviously, what he does is to look for the necessary condition of the possibility of obligation and of acting for the sake of duty alone, in accordance with a categorical imperative; and he finds this necessary condition in the idea of freedom.”43 7. However, according to Kant, “freedom cannot be proved. Hence it is perhaps more accurate to say that the condition of the possibility of a categorical imperative is to be found ‘in the idea of freedom’. To say this is not, indeed, to say that the idea of freedom is a mere fiction in any ordinary sense. In the first place the Critique of Pure Reason has shown that freedom is a negative possibility, in the sense that the idea of freedom does not involve a logical contradiction. And in the second place we cannot act morally, for the sake of duty, except under the idea of freedom. Obligation, ‘ought’, implies freedom, freedom to obey or disobey the law. Nor can we regard ourselves as making universal laws as morally autonomous, save under the idea of GMM, 435. Copleston, 331. 40 Copleston, 331-332. 41 Copleston, 332. 42 Copleston, 333. 43 Copleston, 333. 39 freedom. Practical reason or the will of a rational being ‘must regard itself as free; that is, the will of such a being cannot be a will of its own except under the idea of freedom (GMM, 448).”44 8. “The idea of freedom is thus practically necessary; it is a necessary condition of morality.”45 9. “At the same time the Critique of Pure Reason showed that freedom is not logically contradictory by showing that it must belong to the sphere of noumenal reality, and that the existence of such a sphere is not logically contradictory. And as our theoretical knowledge does not extend into this sphere, freedom is not susceptible of theoretical proof. But the assumption of freedom is a practical necessity for the moral agent; and it is thus no mere arbitrary fiction.”46 A. “The practical necessity of the idea of freedom involves, therefore, our regarding ourselves as belonging, not only to the world of sense, the world which is ruled by determined causality, but also to the intelligible or noumenal world. Man can regard himself from two points of view. As belonging to the world of sense, he finds himself subject to natural laws (heteronomy). As belonging to the intelligible world, he finds himself under laws which have their foundations in reason alone.”47 10. Implicit metaphysics – assuming noumenal world 11. “And thus are categorical possible because the idea of freedom makes me a member of an intelligible world. Now if I were a member of only that world, all my actions would always accord with the autonomy of the will. But since I intuit myself at the same time as a member of the world of sense, my actions ought so to accord. This categorical ought presents a synthetic a priori proposition, whereby in addition to my will as affected by sensuous desires, there is added further the idea of the same will, but as belonging to the intelligible world, pure and practical of itself, and as containing the supreme condition of the former will insofar as reason is concerned.”48 12. The condition of the will of the phenomenal world is found in the noumenal world – in a world we can know nothing of, not even its existence…contingency upon something we cannot even know… 13. “Thus the question as to how a categorical imperative is possible can be answered to the extent that there can be supplied the sole presupposition under which such an imperative is alone possible – namely, the idea of freedom. The necessity of this presupposition is discernible, and this much is sufficient for the practical use of reason, i.e., for being convinced as to the validity of this imperative, and hence also of the moral law; but how this presupposition itself is possible can never be discerned by any human reason. However, on the presupposition of freedom of the will of an intelligence, there necessarily follows the will’s autonomy as the formal condition under which alone the will can be determined.”49 14. “In saying here that no human reason can discern the possibility of freedom Kant is referring of course, to positive possibility. We enjoy no intuitive insight into the 44 Copleston, 333. Copleston, 333. 46 Copleston, 333. 47 Copleston, 333-334. 48 GMM, 454. 49 GMM, 461. 45 sphere of noumenal reality. We cannot prove freedom and hence we cannot prove the possibility of a categorical imperative. But we can indicate the condition under which alone a categorical imperative is possible. And the idea of this condition under which alone a categorical imperative is possible. And the idea of this condition is a practical necessity for the moral agent. This, in Kant’s view, is quite sufficient for morality, though the impossibility of proving freedom, indicates, of course, the limitations of human theoretical knowledge.”50 15. Kant can know nothing of this noumenal world b/c he can only know appearances. But now he is implicitly claiming that it exists and claiming that since it exists, it allows man to be free. Thus, he is claiming at least 2 things he cannot know b/c they lay outside of the phenomenal world. Once again, his philosophy is implicitly metaphysics. Or if not, it is contingent. “If a noumenal world exists, then it is in this world that freedom exists…if freedom exists, then the categorical imperative is possible.” 16. It’s not even just a condition, it’s the idea of a condition. 17. Necessity is grounded in contingency! 18. Morality essentially becomes impossible after Kant’s first Critique because the freedom required for moral action cannot be proven, due to the restrictions placed on theoretical knowledge in the Critique. If morality is to be possible, it must rely on a condition and if it lies on a condition, it is contingent…as if…but obviously man is free… 19. But the very impetus to act comes from the causal world…if I am free, then… The Postulates of Practical Reason; Freedom, Kant’s idea of the perfect good, immortality, God, the general theory of the postulates 1. “The ideas, therefore, which Kant declared to be the main themes of metaphysics but which he also judged to transcend the limitations of reason in its theoretical use are here reintroduced as postulates of reason in its practical or moral use.”51 2. Freedom: “A theoretical proof that a rational being is free is, according to Kant, impossible for the human reason. Nonetheless it cannot be shown that freedom is not possible. And the moral law compels us to assume it and therefore authorizes us to assume it. a. “We must note the difficult position in which Kant involves himself. As there is no faculty of intellectual intuition, we cannot observe actions which belong to the noumenal sphere: all the actions which we can observe, either internally or externally, must be objects of the internal or external sense. This means that they are all given in time and subject to the laws of causality. We cannot, therefore, make a distinction between two types of actions, saying that these are free while those are determined. If, then, we assume that man, as a rational being, is free, we are compelled to hold that the same actions can be both determined and free.”52 b. “Kant is, of course, well aware of this difficulty. If we wish to save freedom, he remarks, ‘no other way remains than to ascribe the existence of a thing, so far as it is determinable in time, and therefore also its causality according to the law of natural 50 Copleston, 334. Copleston, 334. 52 Copleston, 335 51 necessity, to appearance alone, and to ascribe freedom to precisely the same being as a thing in itself’” (CPrR, 171) c. “Insofar as a man’s existence is subject to time-conditions, his actions form part of the mechanical system of Nature and are determined by antecedent causes. ‘But the very same subject, being on the other hand also conscious of himself as a thing-initself, considers his existence also in so far as it is not subject to time-conditions, and he regards himself as determinable only through laws which he gives himself through reason.’(CPr.R., 175) And to be determinable only through self-imposed laws is to be free.” d. Again, Kant is claiming to have knowledge of unknowables. e. “The statement, however, that man is noumenally free and empirically determined in regard to the very same actions is a hard saying. But is in one in which, given his premises, Kant cannot avoid.”53 3. Certain things (transcendental Ideas) in Kant’s philosophy can only be true if “I am justified in thinking that I exist, not only as a physical object in the sensible world, but also as a noumenon in an intelligible sphere and supersensible world. And the moral law, being inseparable connected with the idea of freedom, demands that I should believe this.”54 a. We are demanded to believe in something we cannot know. Kant on Religion 1. “Morality leads inevitably to religion” – perhaps this inversion that Kant makes is largely responsible for the overwhelming attitude people – at least in the US – have toward religion. Virtually all of the problems people have with religion are over moral codes…interesting to note…loss of the sacred! 2. “Everything which, apart from a moral way of life, man believes himself capable of doing to please God is mere religious delusion and spurious worship of God.” a. Reduction of religion to morality has led to secularization Kant’s philosophy led to relativism, despite his reactions against it…When morality becomes relative, the very thing that grounds practical faith in God is destroyed and hence faith in God is lost completely. Kant didn’t protect people from atheism, he drove them to it. 3. “Kant’s interpretation of religion was moralistic and rationalistic in character.”55 Concluding Remarks 1. “It cannot be denied, I think, that there is a certain grandeur in Kant’s ethical theory. His uncompromising exaltation of duty and his insistence of the value of the human personality certainly merit respect.”56 2. “We are left here and now with a juxtaposition of the realm of natural necessity and that of freedom. Inasmuch as reason tells us that there is no logically compatible. But this is hardly enough to satisfy the demands of philosophical reflection. For one thing, freedom finds expression in actions which belong to the empirical, natural order. And the mind seeks to find some connection between the two orders or realms. It may not, indeed be 53 Copleston, 336. Copleston, 338. 55 Copleston, 345. 56 Copleston, 345. 54 able to find an objective connection in the sense that it can prove theoretically the existence of noumenal reality and show precisely how empirical and noumenal reality are objectively related. But it seeks at least a subjective connection in the sense of a justification, on the side of the mind itself, of the transition from the way of thinking which is in accordance with the principles of Nature to the way of thinking which is in accordance with the principles for freedom.”57 Belief in God cannot be reduced to practical faith b/c God is a mystery and thus faith in God is necessarily personal. To strip man of this personal aspect of faith runs the risk of eventually propelling him into atheism To act for any reason other than for the sake of duty is to substitute heteronomy for autonomy Ultimately, Kant realizes that nothing is possible without the transcendental Ideas – morality itself is contingent upon them (and thus seems to lose the a priori character it sought after) yet, even though they are the conditions for his system of ethics, he still maintains that nothing can be known of them…man simply must act as if they existed 57 Copleston, 348.