Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of

advertisement

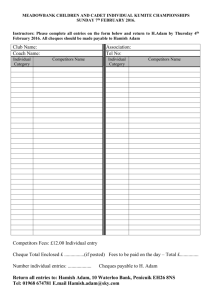

Case No 1 (2009-10): A GILTWOOD TABLE BY JOSEPH PERFETTI Meets Waverley criteria two and three EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Brief Description A table of carved and gilt pine and limewood, with a later top of Korgon(?) porphyry, H. 91.5 x W. 124.5 x D. 62.3 cm. Designed by Robert Adam (1728–1792), the manufacture attributed to Joseph Perfetti (fl. 1760–78 or later), c. 1775–80. The frame was originally painted, and traces of paint survive on the interior; how far the paint survives beneath the gilding has not been ascertained. Some of the carving may have been restored, perhaps including most of the ribbons in the apron, which are painted a lighter grey on the back face than the rest of the frame. 2. Context Provenance The table is one of a pair, which were almost certainly supplied to Henry, Lord Apsley, 2nd Earl Bathurst from 1775 (1714-1794), for Apsley House. The identification is based on their correspondence to a drawing by Robert Adam, inscribed ‘Table for Lady Bathurst, Apsley House’; and the inscription makes it clear that they were made after Lord Apsley’s inheritance of the earldom in September 1775. The tables’ subsequent history is uncertain: they were possibly disposed of by the Marquess Wellesley after he bought Apsley House from the 3 rd Earl Bathurst in 1805, or by his brother the 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852), who purchased the house in 1816 and began to refurbish it in the late 1820s. But there is some evidence to suggest that they were retained at Apsley House during the 1 st Duke’s lifetime (discussed below). They are not recorded in inventories of Apsley House taken in 1854 and 1857, so may have been sold, or removed to Stratfield Saye, after the Duke’s death in 1852. Literature Eileen Harris: ‘Adam at No 1 London’, Country Life, Vol. CXLV, No. 44 (November 1, 2001), 98–101 (pp. 100 (ill.), 101). 3. Waverley criteria The export of the table is objected to on criteria 2 and 3: it is a rare survival from one of Robert Adam’s most important town-house commissions, now largely overlaid by the early 19th-century refit for the Duke of Wellington –when the table too was probably redecorated and equipped with its present top. Its aesthetic importance lies partly in Adam’s design, partly in the exceptional quality of the carving. Its importance for study is enhanced by the technical features that allow us to attribute its manufacture to Joseph Perfetti, one of the group of craftsmen employed by Adam, but of whom little other work is so far known. DETAILED CASE 1. Detailed description of item, and comments. The table (Fig. 1) is one of a pair, identified with Robert Adam’s commission to decorate Apsley House on the strength of the drawing (Fig. 2) showing one leg and the adjacent section of the table’s frieze and apron, inscribed ‘Table for Lady Bathurst, Apsley House’ (Soane Museum, Adam Drawings 49/44). Robert Adam built Apsley House between 1771 and 1778, a period that coincided with Lord Apsley’s term as Lord Chancellor. A number of ceilings, chimney pieces and doorcase friezes in the State Apartments on the first floor survive, but from 1819 onwards Benjamin Dean Wyatt (1775–1855) carried out extensive alterations for the 1st Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), culminating in the creation of the Waterloo Gallery, 1828–30. A dish in the Prussian Service (Fig. 3), displayed at Apsley House, depicts the house before these alterations. Only three rooms on the first floor – now called the Yellow Drawing Room, the Portico Drawing Room and the Piccadilly Room – still have the dimensions laid out by Adam. The table’s manufacture is attributed to the carver and gilder Joseph Perfetti of St Marylebone, London, who from 1762 undertook commissions for the 2nd Earl of Shelburne at Lansdowne House, London, for John Parker (a close friend of Lord Shelburne’s) at Saltram, Devon, and for Henry Knight at Tythegston Court, Glamorganshire. His last recorded work was some frames supplied to Saltram on 4 February 1778, for which John Parker paid £8 17s. (at an unspecified date) to ‘Mrs Perfetti’ – possibly his widow.1 Perfetti’s earlier work for Saltram includes two pairs of tables closely related to the present examples. On 29 January 1771 Parker paid him £41 1s. ‘for table frames for the Great Room Saloon’, and on 31 March 1772 £41 ‘for Table Frames in the Velvet Room’.2 The first pair (Fig. 4) relate to an Adam design of 1768 for ‘a Table Frame for his Grace the Archbishop of York’ (Soane Drawings 17/11; Fig. 5), but as Eileen Harris has well argued, the differences suggest that they were made without direct access to Adam’s drawing.3 For the second pair (Fig. 6), however, Adam supplied a design directly to Parker (Soane Drawings 20/70; Fig. 7). So the similarity of design to the present table is not in itself a reason to attribute this one also to Perfetti. Shared aspects of manufacture, however, strongly indicate that he was responsible. The applicant has noted that the carved swags on the 1772 Saltram tables and the present table have been cut with a fret-saw, and are all formed from sections of lime wood of the same length. Still more idiosyncratic is the use of shaped iron bars to secure the swags (Fig. 8) – formed to the same outline and screwed into the back face of the swags and of the frieze above. This usage is 1 Geoffrey Beard and Christopher Gilbert (eds), Dictionary of English Furniture Makers 1660–1840 (Leeds, 1986), p. 690. The payment may have been made some years later, so Perfetti may well have lived beyond 1778. 2 Eileen Harris, The Furniture of Robert Adam (London, 1963), p. 69 and pls 21 and 22 (inversely numbered to the captions). 3 Ibid. See also Eileen Harris, The Genius of Robert Adam: His Interiors (London, 2001), p. 237. common to both pairs of tables at Saltram and the Apsley House table under consideration. Unlike the Saltram pieces, however, the present table was originally painted, not gilded, as indicated in Adam’s drawing and evinced in traces surviving on the interior (Fig. 9). Adam’s drawing also shows a slab of, seemingly, scagliola or Bossiwork, which would have combined very successfully with the colourful painted frame. The design in Fig. 2 is one of about twenty-six surviving furniture designs by Adam for Apsley House – some of them dated, between 31 January 1778 and 19 June 1779, and some designated for specific rooms. Adam’s floor plans also survive, with room names shown for the upper ground floor and first floor (Figs 10–12). The surviving evidence – from the extant designs and the house as it now stands – presents unanswered questions about the date and original site of this pair of tables. (No inventory of this period, which might throw light on the matter, has been traced.) The normal placement of such a pair would be on the piers of a threewindowed wall in one room. Adam’s floor plans show only three three-bay rooms: the Dining Parlour and the Drawing Room (or Great Drawing Room) on the Parlour Storey (upper ground floor; Fig. 10), and the Second Drawing Room on the Principal Storey (first floor; Fig. 11).4 The Dining Parlour may confidently be excluded: these delicate tables, originally painted, would have been highly unsuitable for a dining room. Moreover, the inscription ‘for Lady Bathurst’ suggests the design was intended for a room in her domain. One of the two drawing rooms is much more likely. These were of the same shape and size, placed one above the other. B. D. Wyatt’s architectural changes of the 1820s have obscured the width of the original piers on the west walls of both rooms. But as far as can be judged from Adam’s plans, the piers could easily have accommodated the tables – and might indeed have rather dwarfed them. For both drawing rooms, however, Adam’s designs show semi-circular, not rectangular, pier furniture: ‘a slab for the Tables in the Great Drawing Room’, dated ‘19th June 1779’ (Soane Drawings 17/46; Fig. 13); and ‘Commode[s] for the second Drawing room at Apsley House’, dated ‘June 1779’ (Soane Drawings 17/43; Fig. 14). One possible explanation is that Lady Bathurst rejected the design and that it was executed for a different client; but this is unlikely in view of the high level of detail proposed in the drawing (Fig. 2), suggesting a late stage in the design process – a refinement to a design that had already been agreed in principle. Another possibility is that the tables were made for one of the more intimate rooms on the second storey, for which no room names are marked on Adam’s plan (Fig. 12). However, since none of these rooms has a three-windowed wall, this seems improbable. 4 Previously it has been suggested that the present table was made for the Bedroom (Eileen Harris, loc. cit. (see Literature)). The applicant has made the alternative proposal of the north pier of the third Drawing Room (also known as ‘the Toilet Room’ and ‘Lady Bathurst’s Dressing Room’). Both of these rooms, however, had only single piers, so could not have accommodated the pair of tables in the conventional arrangement. A third possibility is that this design superseded one of the 1779 designs for pier furniture in the drawing rooms, but this too seems rather unlikely, for the semicircular designs were certainly the more advanced stylistically. Fourthly, it is possible that the rectangular tables were designed and manufactured soon after September 1775, and themselves displaced within a few years by the semicircular pieces in one of the drawing rooms. This explanation is more plausible, bringing the tables much closer in date to the most directly comparable examples in Adam’s repertoire, designed in 1768 and 1771 (discussed above). It is also consistent with the known history of the two drawing rooms’ creation: Adam designed chimneypieces for both rooms in 1774 (Soane Drawings 23/57 and 23/61), and the ceiling of the Second Drawing Room on 6 April 1775 (Soane Drawings 14/13). So he could well have been designing pier furniture for either room soon afterwards. If the tables were displaced from their original site within a few years of being made, they may well subsequently have been deployed opportunistically in another room or rooms. That they were retained by the Duke of Wellington has been suggested because the bluish-grey porphyry of their present slabs appears to match the Korgon porphyry in a pair of monumental candelabra in the Waterloo Gallery (Fig. 16). These formed part of a diplomatic gift presented to the Duke by Tsar Nicholas I, just before his coronation in August 1826, together with three mirror frames, a pair of malachite pier tables and a malachite vase. Whether any slabs of Korgon porphyry were also included in the gift has yet to be investigated.5 The tables may well have been gilded at the same time as the slabs were replaced, for the grey porphyry would have looked very incongruous with the polychrome frames. Their history of alteration can only be surmised, however, for they cannot be matched with any item in the 1854 and 1857 inventories of Apsley House. They may have been sold, or moved to Stratfield Saye, following the 1st Duke’s death in 1852. 2. Detailed explanation of the outstanding significance of the item(s). This table is one of very few pieces that can now be associated with one of Robert Adam’s most important town house commissions. The other major survivals include two pairs of torchères in private collections (one pair with Blairman’s in 1988, the other with Mallett’s in 2000). The table belongs to Adam’s ‘mature style’, as identified by Eileen Harris – lighter and more delicate than his still rather Kentian work of the 1760s, but more vivacious than the highly refined, almost standardized work of the 1780s.6 Saltram, Harewood House, Osterley, and 20 St James’s Square are other commissions from this period. This piece very probably belonged subsequently to the most famous incumbent at Apsley House, the Duke of Wellington, who transformed the interiors, and may well also have been responsible for the transformation of the table – replacing its painted decoration with gilding, and its (apparently) scagliola top with grey porphyry, possibly a gift from the Tsar. While Natalya Guseva and Igor Sychov, ‘Diplomatic gifts from Tsar Nicholas of Russia to the Duke of Wellington’, Apollo, Vol. CVLII, No. 467 (Jan 2001), pp, 34–40. The list of items gifted – not fully transcribed in the article – is probably ‘Fond 468 (St Petersburg, Russian Historical State Archive), referred to in notes 12, 15 and 17. 5 6 Harris, The Furniture of Robert Adam (see note 2), p. 19. the loss of its original condition is in one sense regrettable, its present appearance may reflect a distinguished history, and the personal taste of the Iron Duke. Notwithstanding the new gilding, the refinement of Perfetti’s carving is still conspicuous. Perfetti was one of the ‘regiment of artificers’ employed by Adam, but much less well known than most. His only other identified work is the comparable tables at Saltram – one pair representing his direct execution of a design supplied by Adam, the other perhaps his own adaptation of an Adam design. The idiosyncratic technical features found to be common to all three models, together with the high quality of his carving, may with further research enable other pieces to be attributed to his hand or workshop. Lucy Wood Senior Curator, Furniture Textiles and Fashion Department Victoria & Albert Museum Case prepared with the assistance of James Yorke 20 January 2009 Captions Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 The table under review, designed by Robert Adam for Apsley House, c. 1775–80, the manufacture attributed to Joseph Perfetti. Robert Adam, design for a ‘Table for lady Bathurst, Apsley House’, c. 1775–77 or c. 1780. Sir John Soane’s Museum. View of Apsley House before alterations carried out by B. D. Wyatt in the 1820s, detail of a plate in the Prussian Porcelain Service, c. 1818. One of a pair of giltwood tables made by Joseph Perfetti for the ‘Great Room Saloon’ at Saltram in 1771. Robert Adam, ‘Design of a Table Frame for His Grace the Archbishop of York’, May 1768. Sir John Soane’s Museum. One of a pair of giltwood tables made by Joseph Perfetti for the ‘Velvet Drawing Room’ at Saltram in 1772. Robert Adam, design for ‘Glass & Table frame for John Parker Esqr.’, 1771. Sir John Soane’s Museum. A detail of the table in Fig. 1, showing the iron bars screwed to the swags to secure them to the frame. A detail of the table in Fig. 1, showing traces of the original paint on the inside of the frame, at the top of the legs. Robert Adam, plan of the Parlour Storey (upper ground floor) at Apsley House, n.d. [c. 1771?]. Sir John Soane’s Museum. Robert Adam, plan of the Principal Storey (first floor) at Apsley House, 1771. Sir John Soane’s Museum. Robert Adam, plan of the ‘2 pair Stairs floor’ (second floor) at Apsley House, n.d. [c. 1771?]. Sir John Soane’s Museum. Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 15 Fig. 16 Robert Adam, ‘Design of a slab for the Tables in the Great Drawing Room at Apsley House’, 19 June 1779. Sir John Soane’s Museum. Robert Adam, design for ‘Commode for the second Drawing room at Apsley House’, June 1779. Sir John Soane’s Museum. Robert Adam: Robert Adam, ‘Design for a Commode for the 2nd Drawing Room at Apsley House, 10th October 1777. A pair of candelabra of Korgon porphyry in the Waterloo Gallery at Apsley House; presented by Tsar Nicholas I to the Duke of Wellington in 1826.