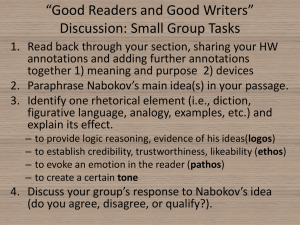

The Gift by Vladimir Nabokov, 1937

advertisement

The Gift by Vladimir Nabokov, 1937-1938 Vladimir Nabokov explained the structure of his book (which is based on the interval of ten years) in the foreword to the publication of The Gift in English as well as in the foreword to his short story The Circle. The action of The Gift starts on April 1, 1926 and finishes on June 29, 1929, thus depicting three years from the life of Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev, a young emigrant living in Berlin. ‘Its heroine is not Zina, but Russian Literature. The plot of Chapter One centers in Fyodor’s poems. Chapter Two is a surge toward Pushkin in Fyodor’s literary progress and contains his attempt to describe his father’s zoological explorations. Chapter Three shifts to Gogol, but its real hub is the love poem dedicated to Zina. Fyodor’s book on Chernyshevsky, a spiral within a sonnet, takes care of Chapter Four. The last chapter combines all the preceding themes and adumbrates the book Fyodor dreams of writing some day: The Gift.’ Indeed, the novel tells a lot about literary life: literary salons, discussions, readings and gatherings. We learn about Yasha Chernyshevsky who writes poems and keeps a diary and who commits a suicide afterwards. The characters of the novel retell the literary plans of Nikolay Chernyshevsky and recite a sonnet devoted to him by an unknown poet. We come across the brilliant lines of a taciturn and mysterious Koncheev. Some heroes quote the philosophical tragedy by Herman Ivanovich Bush as well as his novel which is also absurd. Also, the emigrant critics express their approval of Sedina (which literally means ‘a streak of grey hair’) written by Shirin. We read some fragments of Sukhoshchekov’s pseudo memoirs about the old Pushkin and some extracts from a philosophical treatise written also by the hardly known writer Delaland. The novel gives an open parody on Andrey Bely and Georgy Chulkov. The Holy Family by Marx is retold in verse so that it does not sound boring. All these scenes of literary life form the ‘surface’ of the novel, while at its ‘bottom’ there lies a complex mixture of quotations, parodic hints and reminiscences. Naturally, the novel is focused primarily on the literary life of its main character – Fyodor. In Chapter One Fyodor rereads a newly issued collection of poems and provides comments for it, writes new poems, and thinks about how successful his story about Yasha’s suicide could be. Eventually, Fyodor skips the idea of writing about Yasha, but Nabokov creates this novella and leaves it in the text. In Chapter Two the main character works on the book about his father. Again, it is the author of The Gift (i.e. Nabokov) who completes the aforementioned book. Chapter Three recounts the history of poetic experience of the main hero. Fyodor composes new poems devoted to Zina Merts and starts a book about Nikolay Chernyshevsky. Chapter Four represents a pure novel within a novel. The first complete prose work written by Fyodor depicts Chernyshevsky’s life. In Chapter Five Godunov-Cherdyntsev takes a rest as a writer. The only written work he comes up with is a letter to his mother. He spends the rest of his time on everyday life. He reads reviews; takes part in a funeral; visits a literary gathering; spends a day near the lake; sleeps; have meetings with his beloved; and dreams about a new book or even books. The Gift represents a rare encyclopaedia of genres, micro genres and pseudo genres even for Nabokov. Philologists noted that the romance between the main hero and the Russian literature reflects the basic stages of the latter’s development: (1) Alexander Pushkin’s poetry; (2) Pushkin’s prose (‘A Journey to Arzrum’); (3) Nikolay Gogol’s time; (4) the 1860s (‘Chernyshevsky’s Life’); and (5) the Silver Age of Russian literature. This historical chronology can be correlated with the calendar of the novel. Fyodor’s literary plans – realised and nonrealised ones – form a system of mirrors standing at different angles and reflecting the plot of his life. It is these plans that The Gift builds on. Fyodor’s first step in literary development is a book of poems about his childhood. This imaginary book contains fifty twelve-line poems. Eighteen of them (among which eight in full) are presented in the novel to some degree. Many years later Nabokov published these poems in his separate book, thus authorising distribution of Fyodor’s works. The iambic tetrameter of the book sounds like a quotation from Pushkin’s epoch. However, the author’s idea is to deliberately place this book outside any temporal framework. ‘The author sought on the one hand to generalize reminiscenses by selecting elements typical of any successful childhood,’ says an imaginary critic in his book review. Actually, this is the way the poet sees himself. In Chapter One of The Gift these poems are not presented alone. Nabokov places them in the frame of an imaginary critical article which turns out to be the second (prosaic) description of a lucky childhood. At the same time, the mysterious logic of the novel which is not fully understood and controlled even by the author leads Fyodor to other issues and to new dimensions. Already in Fyodor’s poems the fictitious critic sees not only the flesh of poetry but also the ghost of transparent prose. The second self of the main hero (Koncheev) will even more definitely say in the final imaginary talk of the first chapter: ‘By the way, I’ve read your very remarkable collection of poems. Actually, of course, they are but the models of your future novels.’ One of such models has already been suggested in the first chapter: a young man, the miserable self-murderer Yasha Chernyshevsky (who resembles Fyodor), becomes a passing hero in ten pages of the narrated plot. Yasha is one of the direct opposites of Fyodor. They have radically different approaches to life: the former hates life, while the latter loves it. Another attempt to develop Fyodor’s literary talent is a book about his father. The meeting with his mother and ‘the transparent rhythm of Arzrum’ – the purest sound of Pushkin’s tuning fork – give a direct impetus to the new work. Fyodor’s father appears at the centre of children’s paradise, the paradise of the past left in Russia. His image acquires legendary, mythological and almost divine features. Fyodor’s father is endowed with all possible virtues. He is a traveller, a witty man, a hard worker, a remarkable scientist, and a happy family man whose generosity evokes common admiration. He does not just die. He disappears somewhere in the world ‘ruffled by wars and revolutions’, and constantly penetrates his son’s imagination, coming to his dreams. However, again Fyodor does not manage to write a well-structured and clear book which dissolves in the mixture of drafts, sketches and extracts. It is only the third try at writing prose that is brought to completion by Godunov-Cherdyntsev. The novel Chernyshevsky’s Life does not dissolve in the stream of Fyodor’s life, but is isolated in a separate chapter. This fourth chapter, which gained even more popularity that the whole novel did, was omitted in the first publication of The Gift in the literary journal Sovremennye Zapiski. Although the chapter was included in a separate publication of 1952, it is regarded as an independent text belonging to Nabokov, but not to imaginary Fyodor. Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s origin, character, views on art, and finally the activity to which he devoted all his life are all opposite and antipathetic to the author of Chernyshevsky’s Life. Fyodor (and Nabokov) sincerely shows an ironical attitude to the attempts at canonising the style of Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done: ‘The drolly circumstantial style, the meticulously inserted adverbs, the passion for semicolons, the bogging down of thought in midsentence and the clumsy attempts to extricate it (whereupon it got stuck at once elsewhere, and the author had to start worrying it out all over again), the drubbing-in, rubbing-in tone of each word, the knightmoves of sense in the trivial commentary on his minutest actions, the viscid ineptitude of these actions (as if some workshop glue had got onto the man’s hands, and both were left), the seriousness, the limpness, the honesty, the poverty—all this pleased Fyodor so much, he was so amazed and tickled by the fact that an author with such a mental and verbal style was considered to have influenced the literary destiny of Russia, that on the very next morning he signed out the complete works of Chernyshevsky from the state library.’ Yet the author’s intonation and evaluation radically change with the development of the plot. Nabokov extracts a weak and vulnerable person from the shell of a revolutionary democrat, from the shining framework of a liberal icon. This person is poorly adapted to the social role fallen on him, but yet plays this role to the end and with dignity. Accordingly, the mocking causticity is gradually but obviously replaced with pity, understanding and compassion. On the one hand, Nabokov sarcastically remarks on Chernyshevsky’s poverty and inconsistency, as well as his shyness in relations with women; he formulates a famous ‘aesthetic theory’ based on thoughts of a weak-sighted theoretician and tastefully describes the difficulties in Chernyshevsky’s expression. On the other hand, the author suddenly depicts Chernyshevsky’s meeting with Alexander Herzen in diagonal rays of the sun. He reveals the strength and power in the letters written in the fortress, and, with Pushkin’s simplicity, describes the scene of Chernyshevsky’s public degradation. Without any touch of irony and causticity Nabokov tells about a fleeting meeting of Chernyshevsky with his wife, about the madness of his son, and the terrible and senseless work in Astrakhan. The last and hopeless attempts of Chernyshevsky to ‘outcry the silence’ turn a lampoon into a tragedy. In the terminal delirium of the hero there appear words ‘God’ and ‘fate’. In Fyodor’s book Chernyshevsky turn out a person who, like Pechorin in Lermontov’s novel, did not manage to guess his fate and who, like his father, did not avoid its troubles. In Chapter Five Godunov-Cherdyntsev does not write anything. He reads book reviews, assists at the funeral of Alexander Yakovlevich Chernyshevsky (a self-murderer’s father), participates in a literary gathering, spends a day at the shore of a lake, has meetings with Zina, and sees his father in his dream. However, this everyday life remains the life of a writer and serves his main work, The Gift. Fyodor remains a writer at every moment of his existence. Going to a shop, he tries to determine the rhythm of the streets in the given city (for example, at first there goes the chemist’s, further there goes the tobacconist’s which is followed by the greengrocer’s, etc.). Thus, he seeks to identify the principle of the city structure. Returning to the newly rented room, he deals with the phenomenon of different viewpoints: ‘Taken by itself, all this was a view, just as the room was itself a separate entity; but now a middleman had appeared, and now that view became the view from this room and no other.’ Fyodor is interested in the issue of his father. In the room of Alexander Yakovlevich he finds the material for the topic of ghosts. In his past he identifies the prototypes of his current acquaintances, while in one of the visitors at a literary gathering he sees a plot of his existence. The issues of everyday life are immediately turned into literary motifs because between them there is coincidental similarity. Nabokov’s main hero views the reality as complying with the harmonious principles of art. One just has to hear the musical notes of fate and grasp its secret meaning. In one’s literary work it is necessary to describe the events which have already occurred in accordance with the structural principles of fate. ‘It’s queer, I seem to remember my future works, although I don’t even know what they will be about. I’ll recall them completely and write them.’ There is one key characteristic in Nabokov’s hero which makes The Gift a unique book in both Nabokov’s meta-novel and in the big literature of the 20th century. It seems that Fyodor has lost almost everything a man can lose: a family, an established everyday life, a motherland, a father, a future, etc. He is poor and lonely. He moves from one apartment to another and lives on account of occasional earnings, selling the surplus benefits of his noble education. He gets robbed. On top of that, he constantly loses his keys. He seems to be a classical outcast who, to make things worse, became poor. But contrary to the evidence, the feeling of loss is alien to Nabokov’s hero. It is philologists who invented an opinion that he is in search of a lost paradise. The Gift is a book about a happy man. Fyodor does not just become happy at the end of the novel. He revels in happiness from the first page to the last one. The happiness experienced by the main hero was of exclusive purity: ‘And then, waking completely to the sounds of the morning, he immediately landed in the very thick of the happiness sucking at his heart, and it was good to be alive, and there glimmered in the mist some exquisite event which was just about to happen.’ In his memoirs about the old Pushkin, Sukhoshchekov gives a formula of human existence which has three components: irrevocability, unrealisability and inevitability. Fyodor agrees with the formula and adds one more component to it: ‘Where shall I put all these gifts with which the summer morning rewards me—and only me? Save them up for future books? Use them immediately for a practical handbook: How to Be Happy? Or getting deeper, to the bottom of things: understand what is concealed behind all this, behind the play, the sparkle, the thick, green greasepaint of the foliage? For there really is something, there is something! And one wants to offer thanks but there is no one to thank. The list of donations already made: 10,000 days—from Person Unknown.’ 10,000 days is a formula of human life. Naturally, this formula primarily includes a happy childhood, creative work and love. However, there are also other constituents. One of Fyodor’s happiest days holds practically no events: it includes solitude at the lake shore, the forest, the sun, an imaginary talk with Koncheev, the stolen clothes and running home in the rain. Simple details of everyday life exude a feeling of happiness. His father needed the whole Asia for hunting, while Fyodor created his paradise in a suburb of Berlin. The poetry of railway slopes, a walk in the street or a simple ride in a Berlin tram substitute for travelling, in Fyodor’s view. The main point of Fyodor’s gift – which is only partly expressed in his literary works and fully shown in Nabokov’s novel – is the bliss of sensory cognition, the art of viewing the world and the ability to fill each moment with sensory comprehension of miracle. Fyodor freely moves in space and time. He freely changes points of view, recollects experience of other people, and revives content of books, giving it his own meaning. He has a perfect command of his language and enjoys its various phenomena. For this reason, we come across alliterations, oxymorons and other interesting manifestations of language: «гнусный гнет» очередного новоселья (a boring burden of moving to another house / ‘the vile yoke of recurrent new quarters’), «том томных стихотворений» (a sack of sad poems / ‘volume of languorous poems’), «патока этой патетики» (the sweet syrup of this high-flown speech / ‘this treacly pathos’), «легкая лапа лиственной тени легла ему на левое плечо» (the light leaves of a lime tree cast a shade on his left shoulder / ‘the weightless paw of a leafy shadow descended upon his left shoulder’), «веселое новоселье» (a happy house-warming party / ‘a glad moving in’), etc.1 The metaphor becomes the main instrument that Fyodor uses in prose even more than in poetry. It makes it possible to see what cannot be seen, to give abstract things a volume, a colour and a smell: ‘the twilight of the present’, ‘the light of memory’, ‘the hills of my sorrow’, ‘the precipices of imagination’, ‘a gust of words’, ‘perhaps, he got here from the St. Petersburg of Andrey Bely’, ‘reason’s last tollgate’, ‘a snowy mixture of happiness and horror’, etc. Not only the book about Chernyshevsky but also the rest of the novel serves as a practical lesson in multi-aspect thinking the main hero dreams about. ‘All the trash of life which by means of a momentary alchemic distillation—the “royal experiment”—is turned into something valuable and eternal.’ Among the literary men of the 19th century, perhaps, it is only Afanasy Fet who sang the beauty and harmony of the world so desperately and who glorified a moment as something eternal. Fyodor’s poem about a swallow (‘Perhaps, it is my favourite Russian poem,’ said Nabokov in his interview) seems to be an extract, a catalogue of Fet’s motifs: «Этот 1 Translator’s version is given before the slashes. The extracts from a published translation by Michael Scammell are placed after the slashes and do not reveal the stylistic means being mentioned. листок, что иссох и свалился,/ золотом вечным горит в песнопеньи» (This leaf dried out and fallen,/shines like eternal gold in poetry). Two inserted stories, two micro plots in The Gift seem to be the metaphysical supports in the image of the world. The main hero says that his father did not like folklore. However, sometimes he used to tell a remarkable Kirghiz fairy-tale in which a small sack turns out to have no bottom, thus symbolising insatiability of a human’s eye eager to embrace the entire world. In the terminal delirium of another father (Alexander Yakovlevich Chernyshevsky) there appears a large quotation from the French thinker Delaland, one more ghost created by Nabokov: ‘For our stayat-home senses the most accessible image of our future comprehension of those surroundings which are due to be revealed to us with the disintegration of the body is the liberation of the soul from the eye-sockets of the flesh and our transformation into one complete and free eye, which can simultaneously see in all directions, or to put it differently: a supersensory insight into the world accompanied by our inner participation.’ After finishing The Gift, Nabokov wrote the poem Око (literally translated as ‘an eye’) based on the same Delaland’s image (1939): К одному исполинскому оку Без лица, без чела и без век, Без телесного марева сбоку Наконец-то сведен человек. И на землю без ужаса глянув (совершенно несхожую с той, Что, вся пегая от океанов, Улыбалась одною щекой), Он не горы там видит, не волны, Не какой-нибудь яркий залив И не кинематограф безмолвный Облаков, виноградников, нив; И, конечно, не угол столовой И свинцовые лица родных – Ничего он не видит такого В тишине обращений своих. Дело в том, что исчезла граница Между вечностью и веществом – И на что мне земная зеница, Если вензеля нет ни на чем?2 2 Into one gigantic eye, Without a face, a brow and eyelids, Without a bodily haze, A man has been turned, at last. And, bravely looking at the Earth (which absolutely differs from the one that was covered with patches of oceans all around and smiled with one cheek), He doesn't see any mountains or waves. Nor he sees a bright bay Or the silent cinema Of clouds, vineyards and grain fields; The human eyes contemplate the magic diversity of the Earth, while a soul that left its body and turned into one single eye cannot see anything. Another Delaland’s pseudo quotation says that the belief in God is only a local truth, a truth existing in one region. Further, we read a line of reasoning suggested by an indefinite person: either Delaland or Alexander Yakovlevich or Fyodor or Nabokov: ‘The other world surrounds us always and is not at all at the end of some pilgrimage. In our earthly house, windows are replaced by mirrors; the door, until a given time, is closed; but air comes in through the cracks.’ However, later the narrator hears the last words of dying Nikolay Chernyshevsky: ‘What nonsense. Of course there is nothing afterwards.’ He sighed, listened to the trickling and drumming outside the window and repeated with extreme distinctness: ‘There is nothing. It is as clear as the fact that it is raining.’ Meanwhile, there occurs a sharp change in the plot: ‘And meanwhile outside the spring sun was playing on the roof tiles, the sky was dreamy and cloudless, the tenant upstairs was watering the flowers on the edge of her balcony, and the water trickled down with a drumming sound.’ Does it mean there still exists something after death and the dying man’s feelings are deceptive? After the funeral Fyodor tried to imagine a prolongation of Alexander’s existence round the corner of life and ‘at the same time could not help noticing through the window of a cleaning and pressing shop near the Orthodox church, a worker with devilish energy and an excess of steam, as if in hell, torturing a pair of flat trousers.’ An eye sees only material things and refuses to see anything after death, behind a mirror wall. The hell appears to be a simple earthly cleaning and ironing department situated next to a church. And, again, it is an absolutely earthly and visual metaphor that consoles the main hero: ‘. . . he felt that all this skein of random thoughts, like everything else as well—the seams and sleaziness of the spring day, the ruffle of the air, the coarse, variously intercrossing threads of confused sounds—was but the reverse side of a magnificent fabric, on the front of which there gradually formed and became alive images invisible to him.’ One metaphor is replaced with another: the windows-mirrors turn into the reverse side of a magnificent fabric with animate images on its front. In this case the fabric is also a mirror turned to some invisible observer. The bodily eyes continue to see material things, while the soul appears to see nothing. In any case, if ‘the death is inevitable’ (see the epigraph), Fyodor is going to meet it like a hero in the parable of one old clever Frenchman (another literary man invented by Nabokov appearing in an inserted micro plot): ‘There was once a man… he lived as a true Christian; he did much good, sometimes by word, sometimes by deed, and sometimes by silence; he observed the fasts; he drank the water of mountain valleys (that’s good, isn’t it?); he nurtured the spirit of contemplation and vigilance; he lived a pure, difficult, wise life; but when he sensed the approach of death, instead of thinking about it, instead of tears of repentance and sorrowful partings, instead of monks and a notary in black, he invited guests to a feast, acrobats, actors, poets, a crowd of dancing girls, three magicians, jolly Tollenburg students, a traveler from Taprobana, and in the midst of melodious verses, masks and music he drained a goblet of wine and died, with a carefree smile on his face…. Magnificent, isn’t it? If I have to die one day that’s exactly how I’d like it to be.’ And, naturally, he doesn’t see a canteen’s corner And leaden faces of his relatives. He sees nothing of this kind In the silence of his look. The point is there is no more boundary Between eternity and substance. Do I really need the earthly eyes When nothing in this world has my monogram? ‘If I have to die’ – Fyodor seems to doubt his future death. In Nabokov’s world outlook the death is inevitable. In any case, it does not have a direct attitude to life and does not penetrate it. The fate substitutes for the God in life, and this fate is only a lucky chance of dazzling and transparent existence. Upon narrating his last plot, the main hero pays a shop assistant and goes outside to a stuffy Berlin night with his beloved: ‘And one day we shall recall all this—the lindens, and the shadow on the wall, and a poodle’s unclipped claws tapping over the flagstones of the night. And the star, the star. And here is the square and the dark church with the yellow light of its clock. And here, on the corner, the house.’ Fyodor doesn’t have the keys to this unfamiliar house but he does have the keys to happiness. The philosopher Alexander Pyatigorsky defines Nabokov’s world perception as the philosophy of peripheral vision: ‘It is rather difficult to find another Russian writer of the 20th century to whom the feeling of tragedy is as alien as to Nabokov. This feeling results from direct vision.’ In the tragic 20th century there were indeed too many people who tended to face a tragedy. At the same time, Nabokov probably has no other book in which heroes overcome tragic events so consistently and uncompromisingly as in The Gift. A couple of times Nabokov himself tried to demonstrate direct vision and destroy the fragile aquarium of happiness created in the novel. He made his first attempt in the novella The Circle in which the main character is the son of the village teacher Bychkov mentioned in The Gift. This character used to love Fyodor’s sister in the past. Now in his memory he sees Leshinsky’s summer paradise as something loathsome, while Fyodor’s father turns out, in his view, to be an unremarkable man, a short mouse-coloured ambling horse. The social hatred destroys the optimistic image of the happy childhood and family paradise. The mythical world created in The Gift does not make it possible to take a detached view which is biased and careless. For this reason, Nabokov decided to isolate The Circle – this little satellite of the novel which tells about the general fate and a personal expulsion – from the main text of The Gift. In the sketches of the novel’s continuation (left in the writer’s archives) Fyodor loses his internal integrity and cheerful spirit. He has meetings with a Parisian prostitute. Later a car runs Zina over, and she dies. Fyodor starts a relationship with a new woman. Then a war breaks out. In general, this is another story. These events fully accord with the spirit of the real 20th century. The feeling of melancholy, despair and tragedy goes through the gaps of the mirror house. Fortunately, the continuation remained only in the drafts of The Gift. Meanwhile, the novel appeared to be a book about the happy side of life and to serve as the gratitude to it. In his novel Nabokov seems to follow Pushkin’s thoughts: ‘They say unhappiness is a good school. Perhaps, this is true. However, happiness is the best university.’ The author deliberately finishes The Gift with the light breath of Onegin stanza written in a line, with a dotted line of alliterations, with an open ending; with a thought about the mysterious connection of art with existence: the life does not stop, while a line runs. It is Pushkin’s profile that appeared last in the empty mirror of the novel.