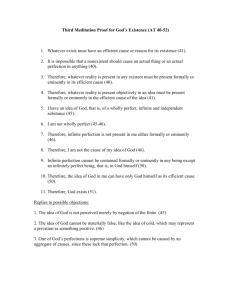

Creating the conditions for transformational change

advertisement