Male Breast Cancer

advertisement

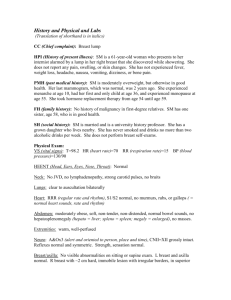

MALE BREAST CANCER Antony Joseph , Kefah Mokbel , Breast Unit, St. George’s Hospital, London Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare condition constituting less than 1 % of all mammary malignancies. However, the incidence of MBC has been rising over the last 2 decades1. This increase is partly due to greater recognition of this condition and improved screening and general awareness. In contrast to female breast cancer (FBC), the incidence shows a unimodal pattern with the highest incidence at the age of 71 compared to FBC which showed a bimodal pattern with highest rates at the age of 52 and 712,3. The risk factors associated with MBC include undescended testes, congenital inguinal hernia, orchidectomy, orchitis, testicular injury, infertility, anti-androgen therapy and Klinefelter’s syndrome1. The data from National Cancer Institute in their Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program showed an increased odds ratio of MBC in those with positive family history4. While genetic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with increased risk of breast cancer in females, only mutations in BRCA 2 have been associated with an increased risk of developing MBC5. This gene is also associated with prostate cancer. The cumulative life-time risk of MBC in carriers of BRCA2 muations is approximately 7%5. Invasive ductal carcinoma is the commonest type accounting for 90% of cases 6. Most MBC tumor specimens are positive for estrogen (ER), progesterone (PgR) and androgen (AR) receptors7. The incidence of Her-2/neu gene positivity is similar to that of FBC8. Her-2 expression is associated with adverse prognosis in FBC; however its role in MBC is currently unclear9. MBC usually presents as a subareolar breast lump, with the majority of cases being stage II infiltrative ductal carcinoma. The involvement of axillary lymph node is seen in approximately 70% of the cases10 and the nipple is involved in 40 -50% of MBC presentations11. Presentation at the ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) stage is relatively rare due to the absence of screening programs and the limited value of mammography in the assessment of breast symptoms. The diagnosis of MBC is usually confirmed by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and/or core biopsy12,13. Mammography has a limited value due to the small size of male breast and the obvious palpable lump at presentation14. MBC is usually treated by modified radical mastectomy including axillary node dissection as studies have shown no significant difference in survival rates compared to radical mastectomy14. The role of sentinel node biopsy (SLNB) in FBC is well documented and is emerging as a new standard of care in men with clinically node negative breast cancer15. The adjuvant therapy available in MBC is based on data from FBC studies, which include hormonal therapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Since MBC tends to be ER positive, endocrine therapy with tamoxifen is an important treatment modality despite the lack of randomized clinical trials. As in FBC, men should ideally receive 5 years of tamoxifen, though most men are treated only for 2 years14. It is also an ideal treatment option for ER positive metastatic carcinoma, in preference to other options such as ablative orchidectomy, adrenalectomy and hypophysectomy which are associated with surgical co-morbidity16. The data on adjuvant chemotherapy is limited, a study by National Cancer Institute showed that chemotherapy achieved a superior 5 year survival rate compared with historical controls17. The current indications for chemotherapy include positive nodes, large primary tumour and hormone receptor negative metastases14. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy is not well defined. The current literature advocates radiation in patients with tumour larger than 1cm and/or presence of >1 metastatic axillary node18. In summary men are more likely to present at an advanced age as well as stage with nodal metastasis. Due to the lower incidence of MBC, the main modalities of treatment currently used have been based on FBC data. Therefore, there is a great potential for randomized controlled trials, especially with regard to hormonal therapy (e.g. third generation aromatase inhibitors) in view of the high ER positivity in MBC. Untill then, the current management of MBC will continue to be based on data from FBC studies. References 1. Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN. Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer 2004 Jul 1;101(1):51-7 3. Anderson WF, Althuis MD, Brinton LA, Devesa SS. Is male breast cancer similar or different than female breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004 Jan;83(1):77-86 4. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. Public-Use Data (1993-97), Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, April 2000. 5. Thompson D, Easton D; Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. American Journal of Human Genetics 2001 Feb 68(2):410-19 6. Stalsberg H, Thomas DB, Roesnblatt KA, Jimenez LM, McTiernan A, Stemhagen A, et al. Histologic types and hormone receptors in breast cancer in men; a population-based study in 282 United States men. Cancer Causes & Control. 1993 Mar 4(2):143-51. 7. Rayson D, Erlichman C, Suman VJ, Roche PC, Wold LE, Ingle JN, Donohue JH. Molecular markers in male breast carcinoma. Cancer 1998 Nov1;83(9): 1947-55 8. Rudlowski C. Friedrichs N. Faridi A. Fuzesi L. Moll R. Bastert G. Rath W. Buttner R. Her2/neu gene amplification and protein expression in primary male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment. 2004 Apr; 84(3):215-23 9. Perkins GH. Middleton LP. Breast cancer in men. BMJ 2003 Aug 2; 327(7409):239-40 10. Temmim L, Luqmani Y A, Jarallah M, Juma I, Mathew M. Evaluation of prognostic factors in male breast cancer. Breast. 2001 Apr;10(2):166-75 11. Yap HY, Tashima CK, Blumenschein R, Eckles NE. Male breast cancer: a natural history study. Cancer 1979; 44:748-54 12. Westenend PJ, Jobse C. Evaluation of fine needle aspiration cytology of breast masses in males. Cancer 2002;96: 101-4 13. Westenend PJ. Core needle biopsy in male breast lesions. J Clinical Pathology 2002;56:863-5 14. Sharon H, Giordano, Aman U, Buzdar, Gabriel N, Hortobagyi. Breast Cancer in men. Annals of Int Med. 2002;137(678-687) 15. Port ER, Fey JV, Cody HS 3rd, Borgen PI. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with male breast carcinoma. Cancer.2001 Jan 15;91(2):319-23 16. Jaiyseimi IA, Buzdar AU, Sahin AA, Ross MA. Carcinoma of the male breast. Ann Intern Med. 1992; 117:771-7 17. Bagley CS, Wesley MN, Young RC, Lipmann ME. Adjuvant chemotherapy in male breast cancer. American J Clin Oncol 1987; 10:55-60 18. Gennari R, Curigliano G, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Zurrida S, Renne G, Galimberti V, Luini A, Orecchia R, Viale G, Goldhrisch A, Vernon U. Male breast cancer: a special therapeutic problem. Anything new? (Review).Int J Oncol 2004 Mar;24(3): 663-70 19. Chakravarthy A. Kim CR. Post-mastectomy radiation in male breast cancer. Radiotherapy & Oncology. 2002 Nov ; 65(2):99-103