Mentoring Handbook - University of Edinburgh

advertisement

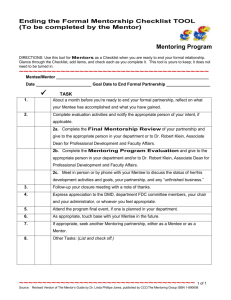

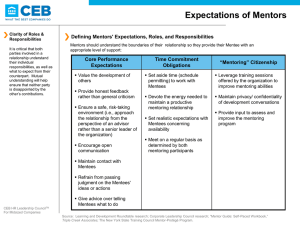

Peer Support: Academic Mentoring Handbook University of Edinburgh Introduction to Mentoring Mentoring has many different meanings in a wide range of contexts, however for the purpose of this programme we regard mentoring as" a Mentor supporting and encouraging a Mentee to manage their own learning in order that they may maximise their potential, develop their skills, improve their performance and become the person they want to be." Eric Parsloe, The Oxford School of Coaching & Mentoring.1 The most common types of mentoring in a university setting include academic mentoring, peer tutoring and peer mentoring2.Mentoring students through the transition to University will support them to manage the change in educational attainment, expectations and become used to being autonomous and self-reliant learners.3 The main aims of mentoring in this context are to support the Mentee to set, work towards and achieve manageable goals to ensure they reach their academic potential. This is a ‘personal/professional’ relationship and is often characterised by the Mentor helping the Mentee to discover their own capabilities and competences. A key aspect of mentoring is that it’s a tool of empowerment which allows the Mentee to realise their academic potential.4 Mentoring is a successful, sustainable model because it uses a resource which is in limitless supply, our own accomplished students. This Handbook goes along with a fully comprehensive training package. Aims/Objectives: 1 To assist a smooth transition to University life or to another stage ie honours by giving undergraduate students the opportunity to meet with current students in more advanced years in the same academic School.5 To help new students feel an early sense of belonging to their peer group, school and the University.6 To assist the Mentee to set, work towards and meet their desired goals. To offer support, guidance and experience to the Mentee in working towards these targets To work in an open, non-judgmental way and encourage the Mentee in their chosen pursuit Facilitate the exploration of needs, motivations, skills and thought processes to assist the Mentee in making sustainable change.7 Support Mentee to develop study skills http://www.mentorset.org.uk/pages/mentoring.htm Driscoll, L., Parkes, K., Tilley-Lubbs, G., Brill, J. and Pitts Bannister, V. (2009). Navigating the lonely sea: Peer mentoring and collaboration among aspiring women scholars, Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnerships in Learning, 17(1), 5-21. 3 http://steer.stir.ac.uk/MentoringResourcesandSupport.php 4 http://www.mentorset.org.uk/pages/mentoring.htm 5 http://scottishmentoringnetwork.co.uk/mentoring-faq.php 6 http://scottishmentoringnetwork.co.uk/mentoring-faq.php 7 http://www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/factsheets/coaching-mentoring.aspx 2 Establish a reciprocal relationship were knowledge is exchanged in both directions & collaborative relationship Mentors are trained, prepared and flexible Why introduce Mentoring The Scottish Mentoring Network outlines the benefits of mentoring as ‘the ability in the Mentee to set manageable, achievable goals and work towards these’.8 Mentoring is of benefit to the University as by mentoring students develop the skills of facilitation, support and issue management and Mentees acquire the skills needed to break down tasks, work towards goals and achieve their targets. It also benefits the Mentor directly, developing their communication, inter-personal and negotiation skills to a high level. Mentors will also learn to collaborate with others to further their learning and ability to achieve their desired outcomes. All of these work well at improving Graduate Attributes. It also directly benefits the Academics, as student’s smaller questions and queries can be answered by others.9 Traditionally mentoring takes the form of one to one meetings but there is also comentoring and group peer-mentoring. Mentoring is extremely useful during transitions supporting the seeking, understanding and applying of 8 9 http://scottishmentoringnetwork.co.uk/mentoring-faq.php http://scottishmentoringnetwork.co.uk/mentoring-faq.php new knowledge, skills and qualities. Guidance and support is important at this time to build confidence10. The concept of continued support after qualification is well established in many professions for example medicine, teaching and social work. It’s a great way to identify potential early, can improve student retention, encourage and support disadvantaged groups and facilitate personal development11. The purpose of this role is to support the Mentee to set, work towards and achieve manageable goals to ensure they reach their academic potential. Additionally the Mentor may help the Mentee to deal with the transition to University and managing the change in educational attainment, expectations and become used to being autonomous and self-reliant learners. There is a significant body of research that reveals that mentoring activities benefit all students, mentoring particularly increases access, progress and success of students who traditionally struggle in tertiary education 12. The most popular definitions, however, are in relation to career advancement and professional development. Driscoll, Parkes, Tilley-Lubbs, Brill and Pitts Bannister (2009) describe mentoring as a process where two or more individuals enter into a coequal relationship that supports mutual mentoring for career and psychosocial validation13. Mentors may boost the self esteem, self efficacy and overall satisfaction of the student with the academic program14 (Ferrari, 2004). Mentoring appears to be most successful when Mentor and Mentee are well matched in the areas of work and life balance, research outcomes and aspirations for career advancement (Ewing et al., 200815). 10 Preparedness to practice, mentoring schemes’ July 1999 NHSE/Imperial College School of Medicine Preparedness to practice, mentoring schemes’ July 1999 NHSE/Imperial College School of Medicine 12 Barnett, J. (2008). Mentoring, boundaries, and multiple relationships: Opportunities and challenges, Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnerships in Learning, 16(1), 3-16. Allen, T., Eby, L. and Lentz, E. (2006). The relationship between formal mentoring program characteristics and perceived program effectiveness, Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 125-153. Fox, A. and Stevenson, L. (2006). Exploring the effectiveness of peer mentoring of accounting and finance students in higher education, Accounting Education: An International Journal, 15(2), 189-202. 13 Preparedness to practice, mentoring schemes’ July 1999 NHSE/Imperial College School of Medicine 14 Ferrari, J. (2004). Mentors in life and at school: Impact on undergraduate protégé perceptions of university mission and values, Mentoring and Tutoring, 12(3), 295305. 15 Preparedness to practice, mentoring schemes’ July 1999 NHSE/Imperial College School of Medicine 11 Values and Principles underpinning mentoring Empowering people to change and shape their future Promoting collaborative rather than competitive work Recognising everyone has the power to pass on knowledge, skills and experiences that would benefit others, not only teachers Developing capability and confidence Builds a sense of belonging to a community of learners What is involved: Mentor Roles & Responsibilities Support the Mentee to make an ‘Action Plan’ outlining their motivation and goals Meet on a one to one or group basis to review the Mentee’s progress towards their desired goals Use questioning techniques to facilitate the Mentee's own thought processes in order to identify solutions and actions16 Utilise active listening and communication skills to ensure the needs of the Mentee are being met within the mentoring relationship17 Share relevant academic experiences/problems you have overcome (if appropriate) Facilitate and encourage autonomous and enquiry-based learning, providing the Mentee with the tools to find their own answers Sign-post the Mentee onto other support services should this be necessary Attend continuous training to ensure the you have the appropriate skills to support the Mentee in their journey An interest in developing themselves and others Capable of building trust and maintaining confidentiality Record meetings for review and evaluation Mentees Role: 16 17 A desire and ability to engage in the mentoring process The time and commitment to pursue their goals An understanding of the role and boundaries of the Mentor Being punctual and prepared for meetings Must respect the confidentiality of the relationship http://www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/factsheets/coaching-mentoring.aspx http://scottishmentoringnetwork.co.uk/mentoring-faq.php Mentor Expectations What we expect you to do: - Offer support and a listening ear to the students you support Have an open, accountable and non-judgemental attitude towards the students you are working with Offer academic guidance and in part general studying good practice Create a safe and welcoming environment were students can share their worries or concerns Be there to consistently support your students Let people know if your not coping Report any concerns to the appropriate person Respect boundaries and confidentiality Respect different cultural values and work in a non-discriminatory manner What we do not expect you to do: - Solve all the Student’s problems To deal with serious welfare issues for example self-harming, eating disorders, suicide. To act as a Counsellor Deal with complaints from students about accommodation issues, finances or immigration. To become inappropriately involved with one of the students you are supporting To take responsibility for the students emotional state or action Helpful Hints Be accessible Check your e-mail, answer messages quickly. Be prepared to meet people at reasonable intervals. Be encouraging Mentoring should provide a safe space for everyone, no matter what they need. Help to build confidence by encouraging new ideas and explorations. Be on time Start and finish on time, and you will encourage participants to do the same. Be respectful Don’t use, or allow others to use discriminatory language. Respect everyone’s abilities as well as their needs Be collaborative, not competitive Remember you are not a teacher – mentoring is about students helping each other Watch out for time thieves Don’t let mentoring take over your life – as tempting as this may be- be aware of how much time you are spending, and protect your own work time. If you are getting too many demands for help, get together with your Key Contact and think about how you can either help more efficiently, or pass on a persistent problem to the right member of staff. What Mentors Bring A well-developed, autonomous learning style A comprehensive understanding of their related discipline Strong communication skills Leadership skills and the ability to work unsupervised The ability to de-compartmentalise the subject area involved, supporting the Mentee to have a thorough understanding of the Discipline Involve mentees in planning how and what they learn Mentors encourage experiential learning Mentors coach Mentees towards their goals Planning Sessions: Mentor Meeting Outline Identify the main focus of the meeting Reflect on successes and challenges since the last meeting Set the Agenda Discussing how to resolve any issues which have emerged Setting, action planning and reviewing the specific goals of the Mentee (this will take up most of the meeting and is the core element) Reflect on how you are progressing through your Learning Log/Journal Clearly plan the logistics of the next meeting Possible Topics: Effective use of the library Settling into University Time management Getting the best out of lectures or seminars Effective note taking Research techniques Avoiding plagiarism Referencing and quotation Essay writing Exam revision Self review Learning from teaching Solving problems Developing good study habits Oral presentations Agenda setting is useful to: Provide structure to the session - to enable you to have a clear picture of what to work through during the session Make sure from the start that Mentee’s have a significant say in what is covered Make sure Mentee’s are encouraged from the start to raise any issues of concern or interests to them Ask the Mentee what they want to cover. Spend as long as it takes to write up points for discussion. You can use your ‘Goal-setting Plan’ for inspiration, when the Mentees’ ideas have been exhausted, agree the order in which you will work through this agenda and how long approximately it will take for each item. Structure the mentoring session by working through the agreed agenda items. You can begin writing up agenda items on the basis of comments or requests made by the Mentee in the previous session. Next, ask open-ended questions to discover information. Providing structure As a Mentor, you need to find the balance between offering enough structure to keep the session on track whilst allowing individuals the freedom to express their ideas. Using session plans when meeting with staff can help this process, as can some of the following ideas. i. Work systematically through the agenda Once the agenda has been agreed, stick to it. Spend some time on each point. Ask open-ended questions to begin discussion. Later, summarise the main ideas related to it before moving on to the next item. ii. Use a variety of techniques to keep the session interesting Keep the session informal but also make sure you focus on what needs to be achieved. Spend some of your time sitting with the Mentee and if appropriate some time at the board. Lead general open-ended discussion. Provide information visually and verbally (see below) iii. Provide information visually and verbally Some students learn better visually, others verbally. Try to make use of both, e.g. by using pictorial representations (diagrams) and verbal illustrations (lists and mnemonics). iv. Summarise important points At the end of each agenda item, summarise the main points. This will work even better if you can encourage the Mentee to provide the summary for you. Asking questions Key to encouraging discussion is asking questions of your mentees that make them do the thinking and talking. Below is some general advice on the types of questions you might find useful to ask: Types of questions i. Probes The task of the Mentor is to help the Mentee to begin to process information beyond the superficial level of delivering the 'right' answer. Examples: “What makes you think that?” “Why do you think that?” “Can you tell me how you arrived at that answer?” ii. Clarification Used when a Mentees’ answer is vague or unclear. The Mentor can ask the Mentee for meaning or more information. Examples: "What do you mean by…?" "Could you explain that in a little more detail?" "Can you be a bit clearer about that?" "Anything else you would like to add?" "Can you be more specific?" "In what way?" iii. Critical Awareness Used when the Mentor suspects the Mentee does not fully understand or wants the student to reflect on an answer. Examples: "What are you assuming here?" "Could you give an example of that?" "How would you do that?" "Are you sure?" "What makes you think that?" "How have you come to that conclusion?" iv. Refocus Encourages the Mentee to see a concept from another perspective by focusing on relationships. Examples: "How is that related to…?" "How does that tie into …?" "How does that compare with …?" Redirecting Questions (How to effectively turn questions back to the Mentee or How not to give answers) There will be times, especially in early sessions, when the Mentee will expect you to provide direct answers to their questions. There may be times when it is appropriate for you to answer questions, however, mentoring sessions should be about discussion of ideas, and so mentees’ should be discouraged from taking the easy option of Mentor telling them what they need to know. If the level of direct questioning becomes a problem, it may be worth reminding the Mentee that a mentoring session is NOT a tutorial, or lecture. Some useful, general redirection questions "What do you think about that?" "What information would you need to answer that?" "Let's try and work that out together." Other useful and challenging process questions "What do you need to do next?" "Can you suggest another way to think about this?" "What is it?" (i.e. definition) "What is its purpose?" (i.e. why) "When would you use it?" The following are some ways of encouraging participation: i. Ask open-ended questions The best questions are usually open-ended (that require more than a yes, no or short answer). Open-ended questions are better because they require Mentees’ to provide lengthy and therefore more substantial responses. The more Mentees’ talk, the better the Mentor is able to understand their ideas and thinking. ii. Encourage student verbalisation As discussed above, when Mentees put their ideas into words it helps them to process information. Also, when a Mentee verbalises an idea it helps their learning processes. iii. Wait for Mentees’responses Mentees’ may need time to think and gain confidence when asked a question. After a while they will usually respond with an answer or another question. Waiting for answers is a difficult but important skill – it can be very tempting to answer questions or jump in with another question or answer – learn to be patient and this will usually lead to better discussion and more group involvement. iv. Encourage questions Mentees’ questions form the raw material of a mentoring session. Always ask if students have questions and offer plenty of time to answer. v. Redirect questions When asked a direct question, try to turn this back to the Mentee. This is a useful skill to master as it means Mentees’ have to think for themselves and don’t depend on the Mentor for answers. Mentees’ become more confident when able to provide answers for the group. vi. Place the emphasis on Mentees’ ideas Always encourage students to share their thoughts, because students build new concepts upon their own ideas and new course material. vii. Delayed positive reinforcement Remind the Mentee of correct ideas they have offered earlier. viii. Be a role model by using “I” statements yourself The Mentors’ experience can help them relate to the Mentee ix. Give permission to acknowledge fears and anxieties Reassure the Mentee that some parts of their studies are difficult and will probably take some time and effort to understand. x. Avoid interrupting student answers The mentoring session should be a safe and comfortable environment for students to try things out, attempt answers and make mistakes. Remember it is often from making mistakes that our best learning comes about. xi. Use positive reinforcement This can have a positive effect on learning and confidence. Examples of positive reinforcement include offering praise for an answer (even if not correct), using a posture of interest and concern, maintaining eye contact, smiling and nodding and making positive comments. xii. Repeat the Mentee’s responses This can act as positive reinforcement, to summarise or clarify comments and enable others to hear comments. Encouraging independent learning Many students need to learn how to study material effectively and to use their time wisely. Their course handbook will contain aims, objectives, and/or learning outcomes. Each of these will give an indication of what the student is expected to learn and achieve. The Mentees’ can use these and any other course documents as a guide to what to learn. They will also need to discover various ways to find answers to questions. i. Emphasise the importance of text books and their notes. It is all too easy for students to bury their lecture notes away and not look at books until they really have to. ii. Encourage independent effort. iii. Discuss essay strategies, exam strategies and study skills. Offer advice and lead discussion on ideas of appropriate ways to prepare for and write essays, revise for and approach exams. Encourage Mentees’ to learn from assessment. Marking criteria provided in course guidelines can be an important source of information. It can also be pointed out that tutor’s comments are important. Assessment is not just about getting marks. It’s also about learning what to do next time! Encourage students to always be reflective in their work and not just to seek feedback when things have not gone quite right. Confidentiality The particular content of the mentoring sessions is confidential to those within the group. 2: Mentees must have confidence that their discussions and individual contributions to sessions will not be repeated outside the session. 3: However, in order to protect members from accusations of plagiarism, and to ensure that sessions are conducted appropriately, Mentors are required to maintain a record of the discussion topics from each session. 4: For further information on dealing with disclosure please refer to the Code of Confidentiality and the Confidentiality Policy. Boundaries: Personal See the person not the behaviour Maintain your respect for the other person even when they choose not to follow what you believe to be the best course of action Follow what you believe to be the best course of action only if it fits within the project rules Do not feel that you have failed if the relationship does not work out Emotional Try to understand the other person’s thoughts and feelings Remember, you may not understand a situation when you see only a part of it Even if you have had a similar problem, you may not fully understand the other person’s difficulties Everyone has different ways of coping. Your way of coping may not be right for another person Organisational It is your right to ask what the project does to maintain it’s boundaries and if they are consistent with the project’s expectations of volunteers It is your responsibility to maintain contact with the project It is both your right and your responsibility to accept support in your role as a Mentor Do Be aware of your own personal boundaries Avoid getting into situations that could be misinterpreted Think before you say ‘Yes’ Remember that the main focus of the relationship is the needs and progress of the person you are there to support Don’t Take the other person to your own home Get involved in a inappropriate relationship Get emotionally over-involved Give or lend money to the other person If you are ever in doubt about a boundary issue, speak to the Key Contact about it. Mentor/Mentee Contact: Contact with group members will at all times be professional and appropriate to the role of Mentor: 1. Mentors and Mentees will treat each other with respect and courtesy at all times. 2. Mentors’ will advise the Key Contact if his/her Mentee is, or becomes, known to them as a friend outside the context of the group. In these circumstances it is recommended that it would be in the interests of both if the Mentee moves to another Mentor. 3. No personal information, i.e. phone or address will be exchanged or requested from students within the context of the group. Email contact will be made via the student university mail system. Mentors should not ‘friend’ group members on Facebook or any other social media for the duration of the mentoring relationship. 4. If the Mentee raises a welfare concern about him/herself or another, Mentors will advise them to contact the appropriate service within the university, and tell the Key Contact that such a request was made. Mentors will immediately advise the Mentee that such discussions are not part of their role. Mentors will not engage in discussion of the problem, both for their protection, and that of the student concerned. Potential Problem Areas Mentor and Mentee do not bond or feel they are not suited Mentor or Mentee show a lack of commitment to the relationship Either party becoming overly involved Inappropriate relationship forming Difficulties due to time/workload constraints Breaking of confidentiality Relationship is interrupted due to external circumstances Dealing with Difficult Incidents Difficult incidents do not happen often, but it is better to be prepared as far as possible should something occur during your session. We have tried to cover the most likely occurrences here, but the unexpected can always happen! If in doubt, a good rule of thumb is: never try to bluff. If you don’t know something, say that you will find out and come back next week with a response. If you are not sure whether a request or question is appropriate, don’t be pushed into making a response on the spot. Check with the Key Contact. The Complaints Policy will also be made available to both parties should an early resolution not be found. If you encounter any of these issues, particularly around confidentiality then please speak with your Key Contact or Katie Scott Peer Support Development Worker with EUSA at katie.scott@eusa.ed.ac.uk. Learning Log/Journal This provides a valuable opportunity to reflect on how the relationship is going, what has been gained in terms of the Mentors own development, what have been challenges and how have these been faced. Key Questions; What was your initial view of mentoring before becoming involved How has this view changed What have been the key successes What have been the key challenges What strategies did you develop for dealing with these What have you learnt personally from the relationship How do you think your professional development has benefitted from the experience Support and Supervision/ Review Both the Mentor and Mentee should have separate, regular support and supervision which will involve appraising the relationship, reviewing each persons progress and dealing with any issues arising. The frequency of these meetings should be negotiated at the start of the relationship. The Key Contact will also meet with the Mentee and Mentor together to set and review collective goals. The Key Contact may ask you to fill out various documents throughout the mentoring role to ensure it can be fully reviewed and evaluated. Endings It is extremely important that mentoring relationships works to a clearly defined time schedule and comes to a planned end. This allows both the Mentor and the Mentee to deal with the loss of this relationship, ensures all issues are resolved and offers a great opportunity to celebrate what has been achieved by the match. The final meeting may be based around sharing feedback on: To what extent were the goals of the relationship achieved? What have been the main learning outcomes for both parties? What went well, what could be improved, and what are the lessons that have been learnt from this? What are the next steps and future opportunities for both parties? Contact Details If Mentors or Mentees have any further questions about Peer Support please contact your Key Contact or Katie Scott the Peer Support Development Officer with EUSA.