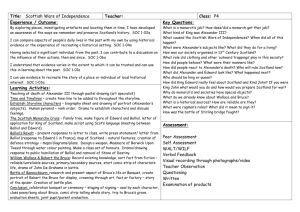

Scottish Wars of Independence

advertisement

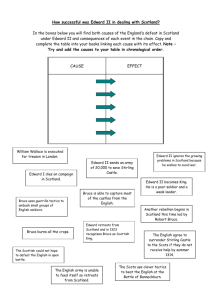

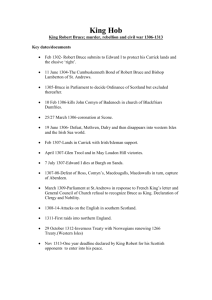

WARS OF SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE Index person is Tom Lowry ‘TL’ The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the independent Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. The First War (1296–1328) began with the English invasion of Scotland in 1296, and ended with the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328. The Second War (1332–1357) began with the English-supported invasion of Edward Baliol and the "Disinherited" in 1332, and ended in 1357 with the signing of the Treaty of Berwick. The wars were part of a great national crisis for Scotland and the period became one of the most defining moments in the nation's history. At the end of both wars, Scotland retained its status as an independent nation. The wars were important for other reasons, such as the emergence of the longbow as a key weapon in medieval warfare. The First War of Independence: 1296–1328 King Alexander III of Scotland died in 1286, leaving his four-year old granddaughter Margaret (called "the Maid of Norway") as his heir. In 1290, the Guardians of Scotland signed the Treaty of Birgham agreeing to the marriage of the Maid of Norway and Edward of Caernarvon, the son of Edward I, who was Margaret's great-uncle. This marriage would not create a union between Scotland and England because the Scots insisted that the Treaty declare that Scotland was separate and divided from England and that its rights, laws, liberties and customs were wholly and inviolably preserved for all time. However, Margaret, travelling to her new kingdom, died shortly after landing on the Orkney Islands around 26 September 1290. With her death, there were 14 rivals for succession. The two leading competitors for the Scottish crown were Robert de Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale (22nd GGF of TL) (grandfather of the future King Robert the Bruce; (19th GGF of TL) and John Balliol, Lord of Galloway. Fearing civil war between the Bruce and Balliol families and supporters, the Guardians of Scotland wrote to Edward I of England (24th GGF of TL), asking him to come north and arbitrate between the claimants in order to avoid civil war. Edward agreed to meet the guardians at Norham in 1291. Before the process got underway Edward insisted that he be recognized as Lord Paramount of Scotland. During the meeting, Edward had his army standing by, thus forcing the Scots to accept his terms. He gave the claimants three weeks to agree to his terms. With no King, with no army ready, and King Edward's army at hand, the Scots had no choice. The claimants to the crown acknowledged Edward as their Lord Paramount and accepted his arbitration. Their decision was influenced in part by the fact that most of the claimants had large estates in England and, therefore, would have lost them if they had defied the English king. However, many involved were churchmen for whom such mitigation cannot be claimed. On June 11, acting as the Lord Paramount of Scotland, Edward I ordered that every Royal Scottish Castle be placed temporarily under his control and every Scottish official resign his office and be re-appointed by him. Two days later, in Upsettlington, the Guardians of the Realm and the leading Scottish nobles gathered to swear allegiance to King Edward I as Lord Paramount. All Scots were also required to pay homage to Edward I, either in person or at one of the designated centers by 27 July 1291. There were thirteen meetings from May to August 1291 at Berwick, where the claimants to the crown pleaded their cases before Edward, in what came to be known as the 'Great Cause.' The claims of most of the competitors were rejected, leaving John Balliol, Bruce, Floris V, Count of Holland and John de Hastings of Abergavenny, 2nd Baron Hastings, as the only men who could prove direct descent from David I, King of Scotland (27th GGF of TL). On August 3, Edward asked Balliol and Bruce to choose forty arbiters each, while he chose twenty-four, to decide the case. On August 12, he signed a writ that required the collection of all documents that might concern the competitors' rights or his own title to the superiority of Scotland, which was accordingly executed. Balliol was named king by a majority on 17 November 1292 and on November 30 he was crowned King of Scots at Scone Abbey. On December 26, at Newcastle upon Tyne, King John Bslliol swore homage to Edward I for the Kingdom of Scotland. Edward soon made it clear that he regarded the country as a vassal state. Balliol, undermined by members of the Bruce faction, struggled to resist, and the Scots resented Edward's demands. In 1294, Edward summoned John Balliol to appear before him, and then ordered that he had until 1 September 1294 to provide Scottish troops and funds for his invasion of France. On his return to Scotland, Balliol held a meeting with his council and after a few days of heated debate, plans were made to defy the orders of Edward I. A few weeks later a Scottish parliament was hastily convened and twelve members of a war council (four Earls, Barons, and Bishops, respectively) were selected to advise King John. Emissaries were immediately dispatched to inform King Philip IV of France (19th GGF of TL) of the intentions of the English. They also negotiated a treaty by which the Scots would invade England if the English invaded France, and in return the French would support the Scots. The treaty would be sealed by the arranged marriage of Edward Balliol (John's son) and Jeanne de Valois (Philip's niece). Another treaty with King Eric II of Norway was hammered out, in which for the sum of fifty thousand groats he would supply one hundred ships for four months of the year, so long as hostilities between France and England continued. Although Norway never acted, the Franco-Scottish alliance, later known as the Auld Alliance, was renewed frequently until 1560. It was not until 1295 that Edward I became aware of the secret Franco-Scottish negotiations. In early October, he began to strengthen his northern defenses against a possible invasion. It was at this point that Robert Bruce, 6th Lord of Annandale (21st GGF of TL); father of the future King Robert the Bruce) was appointed by Edward as the governor of Carlisle Castle. Edward also ordered John Balliol to relinquish control of the castles and burghs of Berwick, Jedburgh and Roxburgh. In December, more than two hundred of Edward's tenants in Newcastle were summoned to form a militia by March 1296 and in February a fleet sailed north to meet with his land forces in Newcastle. The movement of English forces along the Anglo-Scottish border did not go unnoticed. In response, King John Balliol summoned all able-bodied Scotsmen to bear arms and gather at Caddonlee by 11 March. Several Scottish nobles chose to ignore the summons, including Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, whose Carrick estates had been seized by John Balliol and reassigned to John 'The Red' Comyn. Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick had become Earl of Carrick at the resignation of his father earlier that year. Beginning of the war: 1296–1306 The First War of Scottish Independence can be loosely divided into four phases: the initial English invasion and success in 1296; the campaigns led by William Wallace, Andrew de Moray (21st GGF of TL) and various Scottish Guardians from 1297 until John Comyn negotiated for the general Scottish submission in February 1304; the renewed campaigns led by Robert the Bruce following his killing of The Red Comyn in Dumfries in 1306 to his and the Scottish victory at Bannockburn in 1314; and a final phase of Scottish diplomatic initiatives and military campaigns in Scotland, Ireland and Northern England from 1314 until the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328. The war began in earnest with Edward I's sack of Berwick in March 1296, followed by the Scottish defeat at the Battle of Dunbar and the abdication of John Balliol in July. The English invasion campaign had subdued most of the country by August and, after removing the Stone of Destiny from Scone Abbey and transporting it to Westminster Abbey, Edward convened a parliament at Berwick, where the Scottish nobles paid homage to him as King of England. Scotland had been all but conquered. The revolts which broke out in early 1297, led by William Wallace, Andrew de Moray and other Scottish nobles, forced Edward to send more forces to deal with the Scots, and although they managed to force the nobles to capitulate at Irvine, Wallace and de Moray's continuing campaigns eventually led to the first key Scottish victory, at Stirling Bridge. Moray was fatally wounded in the fighting at Stirling, and died soon after the battle. This was followed by Scottish raids into northern England and the appointment of Wallace as Guardian of Scotland in March 1298. But in July, Edward invaded again, intending to crush Wallace and his followers, and defeated the Scots at Falkirk. Edward failed to subdue Scotland completely before returning to England. There have been, however, several stories regarding Wallace and what he did after the Battle of Falkirk. It is said, by some sources, that Wallace travelled to France and fought for the French King against the English during their own ongoing war while Bishop Lamberton of St Andrews, who gave much support to the Scottish cause, went and spoke to the Pope. Wallace was succeeded by Robert Bruce and John Comyn as joint guardians, with William de Lamberton, Bishop of St Andrews being appointed in 1299 as a third, neutral Guardian to try and maintain order between them. During that year, diplomatic pressure from France and Rome persuaded Edward to release the imprisoned King John Balliol into the custody of the Pope, and Wallace was sent to France to seek the aid of Philip IV; he possibly also travelled to Rome. Further campaigns by Edward in 1300 and 1301 led to a truce between the Scots and the English in 1302. After another campaign in 1303/1304, Stirling Castle, the last major Scottish-held stronghold, fell to the English, and in February 1304, negotiations led to most of the remaining nobles paying homage to Edward and to the Scots all but surrendering. At this point, Robert Bruce and William Lamberton may have made a secret bond of alliance, aiming to place Bruce on the Scottish throne and continue the struggle. However, Lamberton came from a family associated with the Balliol-Comyn faction and his ultimate allegiances are unknown. After the capture and execution of Wallace in 1305, Scotland seemed to have been finally conquered and the revolt calmed for a period. During the Wars of Scottish Independence the Clan Scrymgeour were supporters of Sir William Wallace. They were confirmed as banner bearers by Sir William Wallace and Parliament on 29 March 1298. The document in which this is recorded is the only contemporary document to have survived in which the names of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce are mentioned together. At this time the chief of the clan was Alexander Scrymgeour (19th GGF of TL). He was later captured by the English and hanged, drawn and quartered in Newcastle in 1306 on the direct orders of King Edward I of England. He was succeeded by Nicholas Scrymgeour (18th GGF of TL) who rode as royal banner bearer when the clan fought at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. King Robert the Bruce: 1306–1328 On 10th February 1306, during a meeting between Bruce and Comyn, the two surviving claimants for the Scottish throne, Bruce quarrelled with and killed John Comyn at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries. ]At this moment the rebellion was sparked again. Comyn, it seems, had broken an agreement between the two, and informed King Edward of Bruce's plans to be king. The agreement was that one of the two claimants would renounce his claim on the throne of Scotland, but receive lands from the other and support his claim. Comyn appears to have thought to get both the lands and the throne by betraying Bruce to the English. A messenger carrying documents from Comyn to Edward was captured by Bruce and his party, plainly implicating Comyn. Having killed Comyn in a church. Bruce knew he would probably be excommunicated by the Pope, ending his chance to become king since legitimate kings had to be crowned by the Archbishop. But before word could travel to the Pope and back, Bruce had himself crowned. Following his coronation, he entrusted the Stone of Scone to Angus Og, Lord of the Isles (17th GGF of TL), to keep it from Edward I. Bruce sent his family to safe keeping in Ireland, but en route they were captured by the English. His brother Nigel was executed, his wife and daughter, Marjorie (18th GGM of TL) were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Bruce then rallied the Scottish prelates and nobles behind him and had himself crowned King of Scots at Scone less than seven weeks after the killing in Dumfries. He then began a new campaign to free his kingdom. After being defeated in battle he was driven from the Scottish mainland as an outlaw. Bruce later came out of hiding in 1307. The Scots thronged to him, and he defeated the English in a number of battles. His forces continued to grow in strength, encouraged in part by the death of Edward I in July 1307. The Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 was an especially important Scottish victory. Angus og MacDonald (17th GGF of TL), Lord of the Isles and chief of Clan Donald, fought on the side of Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannochburn. In 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath was sent by a group of Scottish nobles to the Pope affirming Scottish independence from England. Two similar declarations were also sent by the Clergy and Robert I. In 1327, Edward II of England (18th GGF of TL) was deposed and killed. The invasion of the North of England by Robert the Bruce (19th GGF of TL), forced Edward III of England (17th GGF of TL) to sign the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton on 1 May 1328, which recognized the independence of Scotland with Bruce as King. To further seal the peace, Robert's son and heir David married the sister of Edward III. The Second War of Independence: 1332–1357 Robert the Bruce died in 1328. When Robert the Bruce lay dying, he called his friend, Lord James Douglas to him, and asked him to carry the Bruce's heart to the Holy Land, and to deposit it in the holy sepulcher. Sir James (19th GGF of TL) did take the Bruce's heart to Jerusalem, in a silver casket that hung from his neck. On his passage he learned that King Alfonso, King of Spain, was waging war against the Moors, and Sir James joined in the fight. The Scots headed the charge, and the enemy was routed. While the Spaniards were plundering the camp, Sir James took a small band of men to pursue the Moors. However, the Moors rallied, and Sir James was surrounded. It is said that he took the casket with Bruce's heart in it, and cast it into the densest mass of the enemy, saying "Forward, gallant heart, as thou wert wont! Douglas will follow or die!" He was killed during the battle. Not far from his dead body, the precious casket was found. His surviving knights took him up with care. His flesh was separated from his bones, and buried in holy ground. The heart of the Bruce was taken back to Scotland to be buried at Melrose Abbey. After Robert the Bruce's death, King David II was too young to rule, so the guardianship was assumed by Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray (19th GGF of TL). But Edward III, despite having given his name to the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, was determined to avenge the humiliation by the Scots and he could count on the assistance of Edward Balliol, the son of John Balliol and a claimant to the Scottish throne. Edward III also had the support of a group of Scottish nobles, led by Balliol and Henry Beaumont, known as the 'Disinherited.' This group of nobles had supported the English in the First War and, after Bannockburn, Robert the Bruce had deprived them of their titles and lands, granting them to his allies. When peace was concluded, they received no war reparations. These disinherited were hungry for their old lands and would prove to be the undoing of the peace. The Earl of Moray died on 20 July 1332. The Scots nobility gathered at Perth where they elected Domhnall II, Earl of Mar (19th GGF of TL) as the new Guardian. Meanwhile a small band led by Balliol had set sail from the Humber. Consisting of the disinherited noblemen and mercenaries, they were probably no more than a few hundred men strong. Edward III was still formally at peace with David II and his dealings with Balliol were therefore deliberately obscured. He of course knew what was happening and Balliol probably did homage in secret before leaving, but Balliol's desperate scheme must have seemed doomed to failure. Edward therefore refused to allow Balliol to invade Scotland from across the River Tweed. This would have been too open a breach of the treaty. He agreed to turn a blind eye to an invasion by sea, but made it clear that he would disavow them and confiscate all their English lands should Balliol and his friends fail. The "disinherited" landed at Kinghorn in Fife on August 6. The news of their advance had preceded them, and, as they marched towards Perth, they found their route barred by a large Scottish army, mostly of infantry, under the new Guardian. At the Battle of Dupplin Moor, Balliol's army, commanded by Henry Beaumont, defeated the larger Scottish force. Beaumont made use of the same tactics that the English would make famous in the Hundred Years' War, with dismounted knights in the center and archers on the flanks. Caught in the murderous rain of arrows, most of the Scots didn't reach the enemy's line. When the slaughter was finally over, the Earl of Mar, Sir Robert Bruce (an illegitimate son of Robert the Bruce), many nobles and around 2,000 Scots had been slain. Edward Balliol then had himself crowned as King of Scots, first at Perth, and then again in September at Scone Abbey. Balliol's success surprised Edward III, and fearing that Balliol's invasion would eventually fail leading to a Scots invasion of England, he moved north with his army. In October, Sir Archibald Douglas (19th GGF of TL), now Guardian of Scotland, made a truce with Balliol, supposedly to let the Scottish Parliament assemble and decide who their true king was. Emboldened by the truce, Balliol dismissed most of his English troops and moved to Annan, on the north shore of the Solway Firth. He issued two public letters, saying that with the help of England he had reclaimed his kingdom, and acknowledged that Scotland had always been a fief of England. He also promised land for Edward III on the border, including Berwick-on-Tweed, and that he would serve Edward for the rest of his life. But in December, Douglas attacked Balliol at Annan in the early hours of the morning. Most of Balliol's men were killed, though he himself managed to escape through a hole in the wall, and fled, naked and on horse, to Carlisle. In April 1333, Edward III and Balliol, with a large English army, laid siege to Berwick. Archibald Douglas attempted to relieve the town in July, but was defeated and killed at the Battle of Halidon Hill. David II and his Queen were moved to the safety of Dumbarton Castle, while Berwick surrendered and was annexed by Edward. By now, much of Scotland was under English occupation, with eight of the Scottish lowland counties being ceded to England by Edward Balliol. At the beginning of 1334, Philip VI of France offered to bring David II and his court to France for asylum, and in May they arrived in France, setting up a court-in-exile at Château Gaillard in Normandy. Philip also decided to derail the Anglo-French peace negotiations then taking place (at the time England and France were engaged in disputes that would lead to the Hundred Years' War), declaring to Edward III that any treaty between France and England must include the exiled King of Scots. In David's absence, a series of Guardians kept up the struggle. In November, Edward III invaded again, but he accomplished little and retreated in February 1335 due primarily to his failure to bring the Scots to battle. He and Edward Balliol returned again in July with an army of 13,000, and advanced through Scotland, first to Glasgow and then Perth, where Edward III installed himself as his army looted and destroyed the surrounding countryside. At this time, the Scots followed a plan of avoiding pitched battles, depending instead on minor actions of heavy cavalary - the normal practice of the day. Following Edward's return to England, the remaining leaders of the Scots resistance chose Sir Andrew Murray (20th GGF of TL) as Guardian. He soon negotiated a truce with Edward until April 1336, during which various French and Papal emissaries attempted to negotiate a peace between the two countries. In January, the Scots drew up a draft treaty agreeing to recognize the elderly and childless Edward Balliol as King, so long as David II (son of Robert the Bruce) would be his heir and David would leave France to live in England. However, David II rejected the peace proposal and any further truces. In May, an English army under Henry of Lancaster invaded, followed in July by another army under King Edward. Together, they ravaged much of the northeast and sacked Elgin and Aberdeen, while a third army ravaged the south-west and the Clyde valley. Prompted by this invasion, Philip VI of France (20th GGF of ES) announced that he intended to aid the Scots by every means in his power, and that he had a large fleet and army preparing to invade both England and Scotland. Edward soon returned to England, while the Scots, under Murray, captured and destroyed English strongholds and ravaged the countryside, making it uninhabitable for the English. Although Edward III invaded again, he was becoming more anxious over the possible French invasion, and by late 1336, the Scots had regained control over virtually all of Scotland and by 1338 the tide had turned. While "Black Agnes", Countess-consort Dunbar and March (Agnes Randolph; 17th GGM of TL), continued to resist the English laying siege to Dunbar Castle, hurling defiance and abuse from the walls, Scotland received some breathing space when Edward III claimed the French throne and took his army to Flanders, beginning the Hundred Years' War with France. In the late autumn of 1335, Strathbogie, dispossessed Earl of Atholl, and Edward III set out to destroy Scottish resistance by dispossessing and killing the Scottish freeholders. Following this, Strathbogie moved to lay siege to Kildrummy Castle, held by Lady Christina Bruce (21st GGM of TL), sister of the late King Robert and wife of the Guardian, Andrew de Moray. Her husband moved his small army quickly to her relief although outnumbered by some five to one. However, many of Strathbogie's men had been impressed and had no loyalty to the English or the usurper, Balliol. Pinned by a flank attack while making a downhill charge, Strathbogie's army broke and Strathbogie refused to surrender and was killed. The Battle of Culblean was the effective end of Balliol's attempt to overthrow the king of the Scots. So, in just nine years, the kingdom so hard won by Robert the Bruce had been shattered and had recovered. Many of her experienced nobles were dead and the economy which had barely begun to recover from the earlier wars was once again in tatters. It was to an impoverished country in need of peace and good government that David II was finally able to return in June 1341. When David returned, he was determined to live up to the memory of his illustrious father. He ignored truces with England and was determined to stand by his ally Philip VI during the early years of the Hundred Years' War. In 1341 he led a raid into England, forcing Edward III to lead an army north to reinforce the border. In 1346, after more Scottish raids, Philip VI appealed for a counter invasion of England in order to relieve the English stranglehold on Calais. David gladly accepted and personally led a Scots army southwards with the intention of capturing Durham. In reply, an English army moved northwards from Yorkshire to confront the Scots. On October 14, at the Battle of Neville's Cross, the Scots were defeated. They suffered heavy casualties and David was wounded in the face by two arrows before being captured. He was sufficiently strong however to knock out two teeth from the mouth of his captor. After a period of convalescence, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was held prisoner for eleven years, during which time Scotland was ruled by his nephew, Robert Stewart, 7th High Steward (17th GGF of TL). Edward Balliol returned to Scotland soon afterwards with a small force, in a final attempt to recover Scotland. He only succeeded in gaining control of some of Galloway, with his power diminishing there until 1355. He finally resigned his claim to the Scottish throne in January 1356 and died in 1364. Finally, on 3 October 1357, David was released under the Treaty of Berwick, under which the Scots agreed to pay an enormous ransom of 100,000 merks for him (1 merk was ⅔ of an English pound) payable in ten years. Heavy taxation was needed to provide funds for the ransom, which was to be paid in installments, and David alienated his subjects by using the money for his own purposes. The country was in a sorry state then; she had been ravaged by war and also the Black Death. The first installment of the ransom was paid punctually. The second was late and after that no more could be paid. In 1363, David went to London and agreed that should he die childless, the crown would pass to Edward (his brother-in-law) or one of his sons, with the Stone of Destiny being returned for their coronation as King of Scots, however this seems to have been no more than a rather dishonest attempt to re-negotiate the ransom since David knew perfectly well that Parliament would reject such an arrangement out of hand. The Scots did reject this arrangement, offered to continue paying the ransom (now increased to 100,000 pounds). A twenty five year truce was agreed and in 1369, the treaty of 1365 was canceled and a new one set up to the Scots benefit, due to the influence of the war with France. The new terms saw the 44,000 marks already paid deducted from the original 100,000 with the balance due in installments of 4,000 for the next fourteen years. When Edward died in 1377, there were still 24,000 marks owed which were never paid. David himself had lost his popularity and lost the respect of his nobles when he married the widow of a minor laird after the death of his English wife. He himself died in February 1371. By the end of the campaign, Scotland remained independent and remained thus, until the unification of the English and Scottish crowns in 1603, when the Kingdom of England, already in personal union with the Kingdom of Ireland since 1542, was inherited by James VI, King of Scots. The formal unification of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain was completed in the Treaty of Union 1707. Major battles and events Battle of Dunbar (1296) Patrick Graham (18th GGF of TL) was the only Scottish nobleman who refused to retreat, and was killed in the losing battle John Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl, (19th GGF of TL) was captured Battle of Stirling Bridge, (1297) Andrew de Moray (21st GGF of TL) led the Scottish forces with William Wallace, and was killed in the battle James Stewart (19th GGF of TL) participated Lord William Douglas the Hardy (28th GGF of TL) was captured by the English and taken to the Tower of London, where he died Malcolm, Earl of Lennox (19th GGF of TL) participated Battle of Falkirk (1298) Edward I (24th GGF of TL) led the English forces Robert Boyd (18th GGF of TL) participated John Stewart of Bonkhill (21st GGF of TL) led the Scottish archers and was killed in the battle John de Graham (17th GGF of TL) was killed in the battle Robert de Clifford (22nd GGF of TL) led the English forces Battle of Methven (1306) Robert the Bruce was unhorsed and captured by the English. Christopher Seton (21st GGF of TL) killed Bruces’ captor, allowing Bruce to escape and continue the fight Battle of Loudoun Hill, (1307) Robert the Bruce (19th GGF of TL) led the Scottish forces Battle of Bannockburn, (1314) Robert the Bruce (19th GGF of TL) led the Scottish forces. During the battle he split the head of Henry de Bohun, the English commander, with his axe, turning the tide of battle Edward II (18th GGF of TL) led the English forces Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray (19th GGF of TL) commanded the Scottish Vanguard Edward Bruce (18th GGF of TL), brother of Robert the Bruce, led the 3rd Scottish division Lord James Douglas (19th GGF of TL) commanded a Scottish division Walter Stewart (18th GGF of TL) commanded a Scottish division Malcolm Drummond (19th GGF of TL) employed caltraps (4-pringed spike that embedded horses’ feet – the caltrap is part of the Drummond coat of arms) Robert Boyd (18th GGF of TL) participated Robert de Clifford (22nd GGF of TL) was killed fighting for the English Battle of Halidon Hill, 1333 Edward III (17th GGF of TL) led the English forces Robert Stewart (Robert II of Scotland) (17th GGF of TL) commanded the center of the Scottish forces Robert Boyd (18th GGF of TL) was killed in battle Archibald Douglas (19th GGF of TL) led the Scottish forces and was killed in battle Andrew Murray (20th GGF of TL) participated Battle of Culblean 1335 Andrew Murray (20th GGF of TL) led the Scottish forces Christina Bruce (21st GGM of TL), wife of Andrew Murray, held Kildrummy Castle until her husband could return Battle of Neville's Cross, 1346 Sir Thomas Boyd (17th GGF of TL) was taken prisoner by the English Patrick Dunbar, Fifth Earl of Dunbar (17th GGF of TL) commanded the right flank of the Scottish army Robert II Stewart (17th GGF of TL) participated