Gender and pension reforms in Japan

advertisement

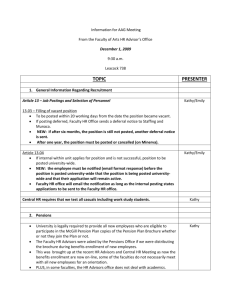

Gender and Pension Reforms in Japan Kikuka Kobatake PhD candidate Department of Social Policy The London School of Economics and Political Science k.kobatake@lse.ac.uk East Asian Social Policy research network (EASP) Second conference Pressure, Policy-Making and Policy Outcome - Understanding East Asian Welfare Reforms Abstract It is well documented that women’s lower levels of pensions are the result of both women’s disadvantages in the labour market and male-oriented pension systems. Being often a main carer, many women compromise their position in the labour market in order to fulfill their care responsibilities. In the case of Japan, the ideology of maternal care is combined, though weakening, with the ‘ie’ ideology, which encourages women to take up the role as main carer for their in-laws. There also exists persistent gender discrimination in the labour market, suppressing women’s gains as wage earners. These disadvantages as wage earners are reproduced or sometimes magnified through pension systems which are based on men’s working experiences. To mitigate the resultant gender gap in pensions, many welfare states, including Japan, have constructed pension systems which are based on male-breadwinner/housewife model and treat women as dependants of their husband rather than as workers in their own right. Nonetheless, the considerable increase in the female labour force in the last couple of decades as well as gender equality movements started putting this arrangement in question. Consequently, the dominant gender model in the state pension systems started changing around the 1990s. Using the conceptual framework of eligibility criteria to benefits elaborated in Sainsbury (1996), this paper examines the changes and continuities of the dominant gender model manifested in recent pension reforms in Japan, and considers their implications for women’s economic welfare in old age. In social insurance systems, people gain an entitlement to benefits on a basis of their monetary contributions. Nonetheless, most public insurance schemes have two other bases of entitlement to benefits, and many women receive pensions through these routes (Sainsbury 1996). The first alternative basis is as wives, which grants benefits on the basis of women’s economic dependency on their husband. The other route to pensions is as mothers or carers, treating care as another form of contribution. In pension systems, this latter access to old age pensions is rather new development, but by the end of 1990s, women in many countries accumulate individual pension entitlements through 1 informal care work for their children or other family members. These three bases may overlap, and certain benefits are available, for example, only to wives in employment or married mothers (see Figure 1). Moreover, these three entitlements may have conflicting interests with each other, operating as a divisive factor for women as a group. Japanese pension insurance is the case in point for this aspect of differential entitlements for women. There have been heated debates that the public pension system treats housewives of the insured employees unfairly favourably than women with other marital and/or employment status. While this line of arguments is not unique to Japan, the extent to which it has influenced political debates on women’s pensions is distinctive. Indeed, the criticism was such that at the turn of the millennium, the government formed a special committee which specifically discussed on women’s pensions (Josei no Lifestyle no Henka nadoni Taioushita Nenkin no Arikata ni Kansuru Kentoukai). This paper places the 2004 pension reform in this context, and examines the reform from the viewpoint of women’s economic welfare in old age. First, the historical development of women’s coverage and debates of the time will be looked at in order to put the current system and ‘women’s pension problem’ in the context. This will be followed by the examination of the gap between the gender model in the pension system and women’s changing life courses. Then, I will look at how the reforms since the 1990s responded to these tensions, and point out the limitations of the reform. Lastly, I will consider the way forward. Figure 1 Bases of entitlement for women Wife Wage earner Mother/ carer 2 Historical development of women’s pensions1 In Japan, the first public pension scheme for workers was established in 1941. Since then, the coverage was extended and the level of benefits was increased. Like in many countries, however, women’s pensions developed in a different way from men. Unlike men, women were included in public pensions as dependants first and foremost, rather than as contributors. Indeed, Japanese women as workers were totally excluded from the first public pension scheme for workers. In 1944, this scheme was transformed into Employee’s Pension Insurance (EPI), and its coverage was extended to women as workers. Nonetheless, it was assumed that most women would leave the labour market on marriage or childbearing, and that they would be provided for by their husband in their old age. Because of this assumption, the main issue brought up as women’s pension problem in the early history of Japanese public pensions was regarding the adequacy of dependency additions for wives and widow’s benefits rather than the issues surrounding women’s own pensions (Fujii 1993). Indeed, in contrast to women’s pensions as wage earners, pensions as wives were included since the inception of public pensions in the form of widow’s pensions, and provision for wives had been repeatedly improved in the course of pension history as dependant allowance for male breadwinners and as widow’s pensions. While EPI was strengthening its nature as a provision for male breadwinners, the flat-rate National Pension Insurance (NPI) was established in 1961 as individually based provision for all people who were not previously covered by public pension system. This included economically inactive wives. Since NPI was decided not to provide dependant allowance, non-employed spouses of the farmers and the self-employed were required to make mandatory contributions to NPI on their own behalf 2 . This arrangement raised questions about housewives of insured employees. There were two strong opinions at the time; one was to exclude housewives from NPI completely on the ground that they would be provided by their husband, and the other was to make housewife’s membership compulsory in line with wives of the self-employed and farmers (Lewis 1981). Concerns were also expressed about ‘women’s pension problem’ of the loss of entitlements through divorce. However, the issue was settled as housewife’s voluntary membership. Here, the seed of contention between housewives of insured employees and other women was planted. Nonetheless, the dominant debate on fairness at the time was about the benefit gap between households rather than individuals. While it was argued that housewives’ participation in the pension scheme would rectify the benefit gap between two-earner employee households and one-earner employee households, the new arrangement now created the gap between households which took out voluntary pensions for housewives and those which did not. Moreover, dependent spouses of insured employees still could be left without any pensions on divorce if they did not make voluntary contribution to NPI. 1 In this article, I focus on schemes for employees in the private sector and the self-employed. For employees in the public sector, there are separate schemes, which operate similar to those for private sector employees in the main. 2 The NPI legislation mandated that the heads of the farming or self-employed household pay contributions both for themselves and their spouse if he/ she was not covered by other public pension schemes. 3 In 1985, a major reform was introduced to transform the system into a current form (see Figure 2). The reform has changed NPI into the flat-rate Basic Pension (BP), which covers all the population in principle, who are aged 20 and over. On top of this basic tier, employees have earnings-related state pensions through EPI. Since this reform, the participation of dependent spouses of insured employees has become mandatory, and they are covered by BP. As the result, all women officially have their own individual pensions regardless of their marital and employment status, solving the pension problem of divorced women. This arrangement also rectified inequality in benefit level between households where housewives took out the voluntary coverage and those where they did not. Nonetheless, this new development for women’s individual pension right did not originate from a gender equality framework. Rather, women’s individual pension right was sought through the traditional assumption of their economic dependency. Moreover, the distinction between wives of employees and the self-employed was retained, making the contribution from the former exempted while that from the latter remained compulsory. This arrangement became a source of debates about favourable treatment of housewives of the insured employees since then. Notwithstanding the positive aspect of this reform in terms of women’s individual pension right, this arrangement in a way consolidated the division among women. Figure 2: The structure of pension system Before the 1985 Reform After the 1985 Reform Employee’s Pension Insurance Employee’s Pension Insurance National Pension Insurance Basic Pension Many criticisms of the reformed arrangement are focused on the non-contribution of 4 housewives of the insured employees while they can receive BP at full rate (Hori 1996). The main points can be summarised as follows: 1. Unfairness among households with different working patterns: Male breadwinner/housewife households receive two units of basic pensions in exchange for one unit of contribution. This is unfair for other types of households because they in effect support the first type of households out of their contributions. 2. Unfairness among economically inactive women: The above mentioned housewife’s entitlement to Basic Pensions is not equally available to all women, but it depends on their husband’s status in the labour market. Thus, wives of the unemployed, wives of the self-employed or single women should pay the premiums to Basic Pensions on their own behalf regardless of their own labour market status unless household incomes are below the threshold for exemption. 3. Unfairness among economically active women: Wives of the insured employees can benefit from the above derived rights as long as they work part-time and their working hours and income are under certain limit (75% of regular workers and 1.3 million yen respectively). On the other hand, even if these ceilings are exceeded, part-time workers are not necessarily guaranteed the coverage to EPI. Thus, part-time workers who work beyond the limit but are not covered by EPI have to pay flat-rate contributions for the same benefits as those granted to housewives. 4. Unfairness as widows: The dual entitlements as wives and wage earners do not lead to additional benefit for survivors. In widowhood, wives with employment record had to choose between their own EPI pensions and widow’s pensions (75% of their husband’s EPI pensions) to top up their own basic pensions. Due to generally low level of women’s EPI pensions, most women would find widow’s benefits higher than their own EPI, thus, give up their own pensions in order to receive widow’s pensions. This means that women who have contributed to the pension scheme would get the same amount of pensions with housewives who have not paid in, if their late husband’s salaries are at the same level. Moreover, women’s entitlement as wage earners offers lower benefits than that for men. When an economically active wife dies, her husband cannot receive survivor’s benefits even if he is economically dependent on his late wife unless he is aged 55 or over. 5. Negative effects for gender equality and for the pension system: These ‘favourable’ treatments of housewives operated as disincentives for women to seek for their own pensions as wage earners, strengthening the gender division of labour, help curtailing women’s position in the labour market, and worsening the finance of the pension system. These criticisms are partly the result of recent general trends towards individualization of benefits, while the Japanese pension system has developed on the basis of households as a unit. Indeed, the government defends the current arrangement by pointing out the equality in both contributions and benefits between households if the aggregate earnings 5 are the same. Widening gap between model and reality With the increase in women’s economic responsibilities as wage earners, as well as gender equality movements, it has become increasingly difficult to sustain the assumptions in the pension system that married women are economically dependent on their husband. Against this background, demands for some amendments for women’s entitlement as wage earners are increasingly gaining ground. On the other hand, due to the broad definition of housewives in the pension system, a significant number of women who work part-time are covered as wives rather than as wage earners despite their link with the labour market. In 2002, 41% of employed women worked part-time, and about 1.2 million people were covered as dependent spouses of insured employees. With the prospect of further increase in the part-time and other atypical working patterns, the need to reconsider the coverage of non-regular workers, including those who are covered as dependent spouses, is generally acknowledged. The inclusion of part-time workers into the system as wage earners is also expected to ease the tension between women as wives and women as wage earners. Nonetheless, the 2004 reform decided to postpone the coverage of part-time workers as wage earners rather than as wives. In contrast to the general acknowledgement of the need to improve the entitlement of women as wage earners, proposals to curtail the existing entitlement as wives are strongly resisted. Especially housewives’ entitlement to BP without contribution turns out to be contentious. One of the arguments to defend the arrangement is that it is a necessary redistribution. It is held that the principle of public pension insurance is ‘contribution according to one’s ability to contribute’; thus it would be against this principle as well as not realistic to collect premiums from housewives who have no earnings of their own. The difficulties for women to accumulate their own pensions as individuals due to responsibilities for unpaid work are also cited as the rationale for retaining the arrangement. Regarding the unfairness among economically inactive women, the proponents often defend it citing the difficulties of knowing the incomes of non-employee households as well as those of individuals in such households. Policy development in the 1990s and beyond Policy developments in the 1990s reflected these arguments and they can be summed up as the attempts to ease the tension between women as housewives and women as wage earners, without curtailing the entitlement of the former. In response to the criticism regarding the unfairness as widows (the point No. 4 above), in 1994, the calculation of widow’s pensions was modified so that women’s own monetary contribution can be reflected to a certain extent in the overall pension amount. In addition to the existing two options, widows were enabled to choose the third option, that is, half of late husband’s pensions and half of one’s own. Thus, the balance between male-breadwinner/housewife model and two breadwinner model was rectified to a certain extent. Another new move in pension reforms in the 1990s was to strengthen employed parents’ rights to pensions. In 1994, care credits were introduced for employees on maternity and parental leave, which was subsequently improved in 1999. 6 This arrangement is more in line with income maintenance, granting credits in order to compensate for the lost or lowered incomes due to care work. Thus, those who are outside the labour market are excluded. Moreover, only insured employees are eligible for these credits; others such as the self-employed and part-time workers are excluded from this development. Moreover, while these credits are a significant step forward for those with care responsibilities, this move is more to do with the concerns about the low fertility rate rather than with the recognition of care value per se. Thus, there was no credit introduced for care for frail elderly or disabled people. The reform in 2004 followed the basic path taken in the 1990s, that is, to try to strike a fine balance between the entitlements as wives and as wage earners without harming the vested interest of the former, and without expanding the definition of the latter. Under the banner of ‘supporting parents to raise the next generations’, the reform legislated to extend the maximum period of care credits from one year to three years. In addition, measures were introduced for those who combine employment and childcare; it legislated to use previous earnings for pension calculation purposes if an employee’s earning should decline due to shorter working hours for child-rearing. In response to the criticism regarding survivor’s benefits for women with employment record, the reform legislated that widows should receive their own earnings-related part which would be topped up by the difference between their own pension and the level they would have received before the reform. As a result, while the nominal composition of survivor’s benefits has changed, the final amount of survivor’s benefit remains the same with that before the reform. Although the reform also introduced a minor cut in wives’ entitlement for young widows3, this would affect only a small minority of women. It can be said that the 2004 reform strengthened the entitlement as wage earners but only marginally, while it left the entitlement as wives almost intact. Indeed, the entitlement as wives not only proved to be resilient against the erosion, but also in a way further strengthened in the 2004 reform. The government reiterated the legitimacy of entitlement to BP as wives as the official basic understanding. Furthermore, in response to the concerns about the low level of benefits for divorcees, the reform introduced pension splitting upon divorce. As the result, dependent spouses can claim the entitlement to the former partner’s earnings-related part of benefits upon divorce, further consolidating the entitlement as wives to individual benefit through derived rights. The way forward Overall, the Japanese pension system retains the bias for the entitlement as wives despite the extensive discussions and a series of reforms (see Figure 3). Although additional provisions were introduced for wage earners since the 1990s, the focus of many criticisms, that is, the entitlement to BP as wives or derived rights saw little change during the period. Thus, it is more likely that the criticisms about unfair treatment of housewives and their counterarguments will persist. Figure 3 Bases of Entitlement for women and corresponding benefits after the 2004 3 The reform limited the duration of benefit provision from EPI to 5 years for childless widows aged 30 or below. 7 reform Wife BP Widow’s pension: 75% of + Widow’s husband’s EPI pension: 50% - Survivor’s benefit limited to 5 of husband’s years for childless widows aged EPI and 50% under 30 of own EPI + Half of husband’s EPI for Wage earner BP EPI + credits during divorcee parental leave for BP+EPI + maintained wage level for EPI Mother/ carer calculation during childcare period One proposed way to break this impasse is to cover married part-time workers as wage earners. As mentioned above, although the implementation was postponed, the law legislated that the necessary step should be considered in the next 5 years. However, this measure will still leave women who do not contribute, and they are more likely to be from better off households than those who are covered as part-time workers. The better way forward, therefore, is to reconsider the meaning of contribution. In exchange for the benefits, people are required to make monetary contribution. This leads to the entitlement as wage earners. However, there is another way to support the system i.e. bearing and raising the next generation who support the system, which may lead to the entitlement as carers. Indeed, without this contribution, the system cannot be sustainable. Moreover, if one looks beyond the pension system but wider social security system, it is impossible not to acknowledge the role informal care work plays to contain social expenditure. In that case, is it not possible to consider care work as contributions? Indeed, some countries such as Germany have introduced this kind of arrangement and give credits to both parents and carers regardless of their marital status. In Japan, one of the often used arguments to defend the entitlement as wives is that housewives are playing a valuable role as informal carers, and many women withdraw from the labour market to take up the role. However, covering housewives on the basis of their care work has a flaw of identifying housewives with carers. In many cases, if not most of the cases, these two groups may overlap. But in some cases, they do not. And the popular image of housewives which has caused a series of antagonistic debates is not the former who devote themselves to the care for others, but 8 the latter who enjoy life at others’ cost. Therefore, it would be better to make a distinction between the two, and include carers as contributors in their own rights rather than covering them as dependants. Although there is a danger of consolidating the traditional gender division of labour in this model, the strengthening of women’s pension entitlement as contributors seems to be more desirable than extending the entitlement based on dependency to carers. Nonetheless, although it is important to distinguish between dependency and contribution, there needs to consider women’s pensions from a viewpoint of decent level of benefits. It is well documented that women’s pension level is generally lower than that of men’s, and older women are disproportionately represented in the lower income groups (see OECD(2001), for example). It should also be noted that the entitlement to basic pensions as wives boosts benefit levels for many women. Moreover, consideration should be given to those who cannot ‘contribute’ due to ill health or other reasons. Thus, rather than aiming for an equilibrium between monetary contributions and benefit levels at a low level, the focus should be set on enhancing the general level of women’s pensions. Especially, if BP is for supporting the basic means for living in old age, as it is often mentioned, it should be guaranteed ideally to all, including housewives. The contribution principle, which includes care as contribution, can be then applied to the top-up benefits i.e. EPI in the case of Japanese system. The demand for Basic Pension for all financed by general revenue has a long-history and been repeatedly proposed. Nonetheless, the government has explicitly showed its preference for social insurance systems based on contributions, and the actual measures taken were focused more on the fairness in contribution duties between women with different life courses. However, as long as the system sticks to the narrow definition of contribution, most women as contributors would fair worse than men in old age. While BP should be the key tool for rectifying this situation, its mixed principle of base unit (household and individual) together with narrow definition of contribution has turned BP to be a divisive factor rather than cohesive for women. Conclusion Women’s pensions pose problems in many countries. However, what dimension of women’s pensions is considered to be problematic varies across countries. In Japan, the often vocally expressed issue has been fairness among women. Moreover, rather than questioning the inequality or decency of individuals’ absolute benefit levels, the focus is often on the contribution. Thus, the popular debates of ‘women’s pension problem’ tend to be reduced to the criticisms of housewives’ free-riding, splitting women into housewives and non-housewives, rather than demanding for better pensions for women as a group. One of the proposed solutions for this antagonism is to reduce the number of ‘housewives’ by extending the coverage of EPI to part-time workers. In a series of committee discussions, the need to cover part-time workers into EPI was repeatedly acknowledged not only due to women’s problems but also against the backdrop of increasing flexibility of labour. Thus, although the actual implementation was again postponed, the 2004 reform clearly legislated that necessary steps should be taken in the next five years. On the other hand, another possible way forward was not taken up, that is, care as contribution. Although care credits were introduced, they were in the context of ‘supporting employees with family responsibilities’ against the backdrop of 9 lowering fertility rate. Thus, these credits are only for insured employees and limited to parents. In the debates on fairness in the pension system, the focus has been put on the link between monetary contribution and entitlement. Indeed, under social insurance systems, fairness with regard to contribution and benefits turns out to be a recurrent topic, be it between individuals, households, or generations. However, in these debates, contribution tends to be defined narrowly to the disadvantage for women as a group. Moreover, ‘fairness’ in the proportion between contributions and benefits does not necessarily promise fairness in the resource distribution between different social groups. Thus, in order to reconstruct a pension system which better accommodates women, both the meaning of contribution and fairness in the benefit level should be reconsidered. Bibliography Fujii, Y. (1993). Nenkin to Josei no Jiritsu (Pension and Women's Independence). Josei to Shakai Hosho (Women and Social Security). Tokyo, Tokyo Daigaku Shuppan Kai: 183-202. Hori, K. (1996). "Josei to Nenkin." Kikan Shakai Hosyo Kenkyu 31(4): 353-367. Lewis, P. M. (1981). Family, Economy and Polity: A Case Study of Japan's Public Pension Policy (Unpublished PhD thesis). Sociology. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, University of California, Berkeley. OECD (2001). Ageing and Income: Financial resources and retirement in 9 OECD countries. Paris, OECD. Sainsbury, D. (1996). Gender, Equalitiy and Welfare States. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 10