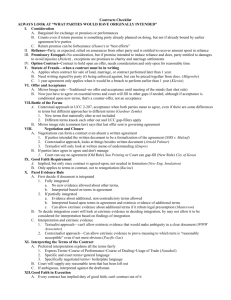

Contracts Outline—2

advertisement