Chapter 7 - Western Oregon University

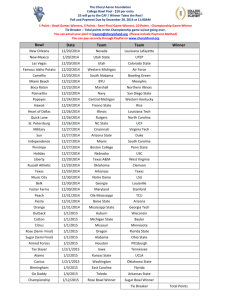

advertisement