Frequently Asked Questions - The University of Scranton

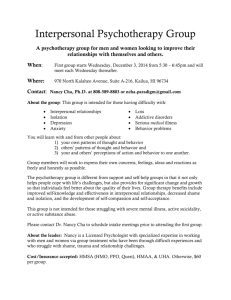

advertisement

Frequently Asked Questions The Division of Psychotherapy’sTask Force on Empirically Supported Therapy Relationships has provokedconsiderable interest and enthusiasm in the professional community. At the same time, it has lead to misunderstandingsand reservations. I will conclude byaddressing frequently asked questions (FAQs) aboutthe Task Force’s objectives and results. What is the relationship of the APA Division 29 TaskForce to the Division 12 Task Force (now the standing Committee on Science andPractice)? Questions aboundregarding the connection of the Division of Psychotherapy (29) and the Societyof Clinical Psychology (12) Task Forces, probably because they are bothdivisions of theAmerican Psychological Association. Organizationally, the Task Forces are separate creatures, reporting todifferent divisions. Their respective foci obviously diverge: one looking attherapist contributions to the relationship and patient responsiveness, theother looking at treatment methods for specific disorders. However, they do share several task forcemembers (Paul Crits-Christoph and Larry Beutler), apublisher (Oxford University Press), and goals (to identify and promulgateevidence-based practices) in common. The aims of theDivision of Psychotherapy Task Force and the aims of previous evidencebased iniatives can be conceptualized in three ways. First, the work of the Division ofPsychotherapy Task Force represents a continuation of previous effortsin that all attempt to apply psychological science to the identification andpromulgation of effective psychotherapy. It is a complementary continuation of the elusive search forevidence-based psychotherapy. Second, the Division of Psychotherapy Task Forceconstitutes an expansion of extant work in that we enlarge the focus toempirically supported relationships. Andthird, the Division 29 Task Force represents, in several ways, a reactionagainst previous decision rules that tend to represent psychotherapy as thedisembodied, manualized treatment of Axis I disorders Are you saying thattechniques or methods are immaterial to psychotherapy outcome? Absolutely not.The empirical research shows that both the therapy relationship and thetreatment method make consistent contributions to treatment outcome. It remains a matter of judgment andmethodology on how much each contributes, but there is virtual unanimity thatboth the relationship and the method (insofar as we can separate them) “work.” Looking at either treatment interventions ortherapy relationships alone is incomplete. We encourage practitioners and researchers to look at multipledeterminants of outcome, particularly client contributions. ¨ Butare you not exaggerating the effects of relationship factors and/or minimizingthe effects of treatments in order to set up the importance of your work? This may be true, but we think not andhope not. With the guidance of TaskForce members and external consultants, we have tried to avoid dichotomies andpolarizations. Focusing on one area –the psychotherapy relationship – in this volume may unfortunately convey theimpression that it is the only area of importance. This is certainly not our intention. Relationship factors are important, andwe need to review the scientific literature and provide clinicalrecommendations based upon that literature. This can be done without trivializing or degrading the effects ofspecific treatments. ¨ What,then, is the association between techniques and therapy relationship? We conceive theassociation broadly and atheoretically. We find anyhard and fast distinctions between them untenable. Further, we do not desire to impose anysingular theoretical vision of their association upon our colleagues. Forhistorical and research convenience, we have made distinctions betweenrelationships and techniques. Words like“relating” and “interpersonal behavior” are generally used to describe howtherapists and patients behave towards each other. In contrast, terms like“technique” or “intervention” are used to describewhat is done in therapy, especially what is done by the therapist. In research and theory, we often treat thehow and the what – the relationships and the interventions, the interpersonaland the instrumental – as separate categories. In reality, of course, what one does and how one does it arecomplementary and inseparable. Toseparate the interpersonal dimension of behavior from the instrumental may beacceptable in research, as done in this book, but disregarding the connectionmay be a fatal flaw when the aim is to extrapolate from research results toclinical practice. Thus, while we focushere on important associations between treatment outcome and qualities of thetherapistpatient relationship, we never forget that what the therapist does isalso influential and inseparable (Orlinsky, 2000). Isn’t your report justwarmed over Carl Rogers? No. While Rogers’ (1957)facilitative conditions are represented prominently in the research base, theycomprise less then 25% of the research we critically review. Morefundamentally, we have moved past simplified notions of a limited and invariantset of necessary relationship conditions. Monolithic theories of change and one-size-fits-all therapyrelationships are out; tailoring the therapy to the unique patient is in. How did the Task Forcehandle the responsiveness problem? Much of theresearch on the effectiveness of psychotherapy processes and relationships isconstrained by the responsiveness problem. Responsiveness refers to behavior that is affected by emerging context,and occurs on many levels, including choice of an overall treatment approach,case formulation, strategic use of particular techniques, and adjustmentswithin interventions (Stiles, Honos-Webb, & Surko, 1998). Experienced therapists tend to be responsiveto the different needs of their clients, providing varying levels ofrelationship elements in different cases. When this occurs, highly effective relational ingredients may have nullor even negative correlations with outcome variables in the cumulativeresearch. Successful responsiveness can confound attempts to findnaturalistically observed linear relations of outcome with therapist behaviors(e.g., interpretations, self-disclosures, feedback). Because of such problems,the statistical relations between relationship variables and outcome variablescannot always be trusted. In thework of the Task Force, chapter authors were aware of the responsivenessproblem (and other limitations of the empirical research on process-outcome linkages). The majority of authors addressed this issuein the chapter sections on the mediating effects of client qualities and as alimitation of the research reviewed. Moreover, the responsiveness premise – that seasoned therapists have learned to respond flexiblyto patient qualities and alter their relational stance on a patient-by-patientor moment-to-moment basis to them – is built into half of the book An interpersonal viewof psychotherapy seems at odds with what managed care and bean counters ask ofme in my clinical practice. How do youreconcile these? It is true that the dominant image of psychotherapy today, among bothresearchers and reimbursers, is as a mental healthtreatment. This “treatment” or “medical”model inclines people to define process in terms of technique, therapists asproviders trained in the application of techniques, treatment in terms ofnumber of contact hours, patients as embodiments of psychiatric disorders, andoutcome as the end result of a treatment episode (Orlinsky, 1989). It is also truethat the Task Force members believe this model to be restricted andinaccurate. The psychotherapy enterpriseis far more complex and interactive than the linear “Treatment operates onpatients to produce effects” (Bohart & Tallman,1999). We would prefer a broader,integrative model that incorporates the relational and educational features ofpsychotherapy, one that recognizes both the interpersonal and instrumentalcomponents of psychotherapy, one that appreciates the bi-directional process oftherapy, and one in which the therapist and patient co-create an optimalprocess and outcome. Finally, it isincontestably and sadly true that psychotherapy research to date has exerted anegligible effect on reimbursement decisions. Won’t these resultscontribute further to deprofessionalizingpsychotherapy? Aren’t you unwittinglysupporting efforts to have any warm, empathic person perform psychotherapy? Perhaps some willmisuse our conclusions in the way you fear, but that is neither our intent norcommensurate with the research. Ittrivializes psychotherapy to characterize it as simply “a good relationshipwith a caring person.” The research shows an effective psychotherapist is onewho employs specific methods, who offers strong relationships, and whocustomizes both discrete methods and relationship stances to the individualperson and condition. That requiresconsiderable training and experience; the antithesis of “anyone can do psychotherapy.” Are psychotherapistsreally able to adapt their relational style to fit the proclivities andpersonalities of their patients? Whereis the evidence we can do this? Relationalflexibility conjures up many concerns, but two of particular import in thisquestion: the limits of human capacity and the possibility of capriciousposturing (Norcross & Beutler, 1997). Although the psychotherapist can, with training and experience, learn torelate in a number of different ways, there are limits to our human capacity tomodify relationship stances. It may be difficult to change interaction stylesfrom client to client and session to session, assuming one is both aware and incontrol of one's styles of relating (Lazarus, 1993) Can one authentically differ fromone's preferred or habitual style of relating? There is meager research on this question. What does exist suggests that experiencedtherapists are capable of more malleability and "mood transcendence"than might be expected. In Gurman's (1973) research, for example, expert therapists appearedto be less handicapped by their own "bad moods" than were their lessskilled peers. From the literature onthe cognitive psychology of expertise, Schacht (1991) affirms that experiencedpsychotherapists are disciplined improvisationalistswho have stronger self-regulating skills and more flexible repertoires thannovices. The research on the therapist'slevel of experience suggests that experience begets heightened attention to theclient (less self-preoccupation), an innovative perspective, and in general,more endorsement of an "eclectic" orientation predicated on clientneed (Auerbach & Johnson, 1977). Indeed, severalresearch studies (see Beutler, Machado, & Neufeldt,1994) have demonstrated that therapists can consistently use different treatmentmodels in a discriminative fashion. The question of whether they canshift back and forth among different relationship styles for a given case isstill unanswered. We expect, however,that this is possible. When doing so, wecaution therapists to be careful that the blending of stances and strategiesdoes not deteriorate into play-acting or capricious posturing. ¨ Whatshould we do if we are unable or unwilling to adapt our therapy to the patientin the manner that research indicates is likely to enhance psychotherapyoutcome? Four possible avenues spring tomind. First, address the matterforthrightly with the patient as part of the evolving therapeutic contract andthe creation of respective tasks, in much the same way one would with patientsrequesting a form of therapy or a type of medication that research hasindicated would fit particularly well in their case but which is not in yourrepertoire. Second, treatment decisionsare the result of multiple, interacting, and recursive considerations on thepart of the patient, the therapist, and the context. A single evidence-based guideline should beseriously considered, but only as one of many determinants of treatment itself. Third, an alternative to theone-therapist-fits-most-patients perspective is practice limits. Without a willingness and ability to engagein a range of interpersonal stances, the therapist may limit his or herpractice to clients who fit the specific range of behaviors he or she has tooffer. And fourth, consider a judiciousreferral to a colleague who can offer the relationship stance (or treatmentmethod or medication) indicated in a particular case. Are these intended aspractice standards? No. These are research-basedconclusions that can lead, inform, and guide practitioners towardevidence-based therapy relationships and responsiveness to patient needs. They are not intended as legal, ethical, orprofessional mandates. As we state inthe Conclusions: “The preceding conclusions do not by themselvesconstitute a set of practice standards, but represent current scientificknowledge to be understood and applied in the context of all the clinical dataavailable in each case.” Well, aren’t these theofficial positions of the Division of Psychotherapy or the American PsychologicalAssociation? No. Neither is true. Isn’tis premature to launch a set of research-based conclusions on thetherapy relationship and patient matching? Science is not a set of answers. Science is a series of processes and steps by which we arrive closer andcloser to elusive answers. Considerableresearch over the past three decades has been conducted on both the generalelements of the therapy relationship and the particular means of adapting it toindividual patients. It is premature toproffer the last word or the definitive conclusion; however, it is time tocodify and disseminate what we do know. We look forward to regular updates on our conclusions. So, are you sayingthat the therapy relationship (in addition to discrete method) is crucial tooutcome, that it can be improved by certain therapist contributions, and thatit can be effectively tailored to the individual patient? Precisely. And thisbook shows specifically how to do so on the basis of the empirical research.

![UW2 - Psychiatric Treatments [2014]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006859622_1-db6167287f6c6867e59a56494e37a7e7-300x300.png)