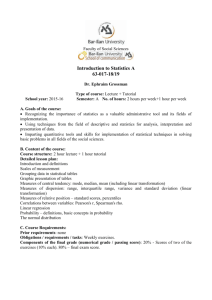

Hooley/Schmucker - James Madison University

advertisement