A Cross-National Perspective on the Nature of School

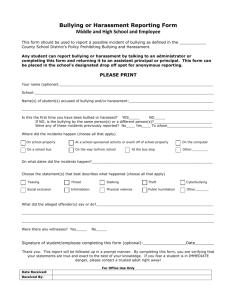

advertisement

Bullying in Northern Ireland 1 A cross-national perspective on school bullying in Northern Ireland: a supplement to Smith et al. (1999) Conor Mc Guckin1 and Christopher Alan Lewis School of Psychology University of Ulster at Magee College Running Head: Bullying in Northern Ireland Address for correspondence: 1 Conor Mc Guckin, School of Psychology, University of Ulster at Magee College, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, BT48 7JL. Bullying in Northern Ireland 2 Summary:- There is great value in exploring the prevalence of school bullying from a cross-national perspective. Smith, Morita, Junger-Tas, Olweus, Catalano, and Slee (1999) presented a cross-national perspective on the nature, prevalence, and correlates of school bullying that encompassed a wide range of countries. However, Northern Ireland was not included, despite it potentially being an important country to include; given its volatile, social, ethnic, and religious history – leading to the concern that the population has become somewhat habituated to low level aggression. Thus, the present paper provides a review of the current literature on school bullying in the Northern Ireland school system. Evidence presented suggests that the incidence of school bullying in Northern Ireland may be higher than those found in the rest of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Bullying in Northern Ireland 3 Overview Bullying in schools is an international problem (Smith & Morita, 1999). As such, there is great value in exploring the prevalence of the phenomenon from a crossnational perspective. In their review of the nature of school bullying, Smith, Morita, Junger-Tas, Olweus, Catalano, and Slee (1999) present a cross-national perspective on the nature, prevalence, and correlates of school bullying that encompasses specific reviews from each of the Scandinavian countries (Finland: Björkqvist & Österman, 1999; Denmark: Dueholm, 1999; Norway: Olweus, 1999a; Sweden: Olweus, 1999b); the U.K. and Republic of Ireland (Ireland: Byrne, 1999; Scotland: Mellor, 1999; England & Wales: Smith, 1999), Latin countries (France: Fabre-Cornali, Emin, & Pain, 1999; Italy: Fonzi, Genta, Menesini, Bacchini, Bonino, & Costabile, 1999; Spain: Ortega & Mora-Merchan, 1999; Portugal: Tomás de Almeida, 1999), central Europe (Switzerland: Alsaker & Brunner, 1999; Poland: Janowski, 1999; The Netherlands: Junger-Tas, 1999; Germany: Lösel & Bliesener, 1999; Belgium: Vettenburg, 1999), North America (Canada: Harachi, Catalano, & Hawkins, 1999a; U.S.A.: Harachi, Catalano & Hawkins, 1999b), the Pacific Rim (Japan: Morita, Soeda, Soeda, & Taki, 1999; Australia: Rigby & Slee, 1999; Aotearoa/New Zealand: Sullivan, 1999), and the developing world (e.g., Palestine, South Africa: Ohsako, 1999). Whilst the list of countries reviewed is long, it is not exhaustive. Of concern here is the omission of a review of the knowledge base regarding bullying behaviours in the Northern Ireland school system. Whilst Northern Ireland may be geographically ‘close’ to countries with reported national data (i.e, Ireland, England, Wales, Scotland), it is also the case that Northern Ireland is culturally ‘distant’ from these countries. Of particular note is the fact that Northern Ireland has endured the impact of over 30 years of violent ethno- Bullying in Northern Ireland 4 political conflict that has its roots in 300 years of Irish history, but was most recently ignited around issues of sectarian discrimination and national sovereignty (Cairns & Darby, 1998). As such, the study of aggression in a region with an experience of cross community conflict and division provides a chance to appraise the possible role of socio-environmental factors in the development and expression of aggressive tendencies in children. The present authors have been working on a detailed and sustained programme of research into the nature, prevalence, and correlates of bullying behaviours among the Northern Ireland population (e.g., Mc Guckin, Lewis, & Shevlin, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2000c, 2001a, 2001b). However, before such work is presented to a wider audience there is a need to provide an overview of the current state of bullying research in Northern Ireland. The present paper provides a supplement to Smith, et al.’s (1999) crossnational review of the nature of school bullying, with a complementary overview of the current knowledge of the nature of school bullying in the Northern Ireland school system in a similar format to that adopted in the country reports in Smith, et al. (1999). Children and the Northern Ireland Conflict Despite paramilitary ceasefires and a reduction in the number of police and army personnel on the streets, aggression and violence are still very much a part of living in Northern Ireland, with sectarian murders and paramilitary punishment beatings still occurring. As the paramilitary organizations work on a ‘no-claim, no-blame’ policy, the ceasefires remain intact and political representatives of these organizations can still hold offices of power in Northern Irelands Government. Also, despite ceasefires from paramilitary organizations on both sides of the community divide, these Bullying in Northern Ireland 5 organizations still attempt to police their own ethnosectarian communities, meting out punishment shootings (knee-capping, elbows and ankles), vicious beatings, and exiling individuals for so-called ‘anti-social behaviours’ (e.g., drugs, car theft). Such aggression permeates many areas of Northern Ireland. Indeed, recent research has highlighted the widespread experience children have of conflict and violence (McAuley, 1988; Children’s Rights Development Unit, 1994; Macksoud & Aber, 1996; Muldoon & Trew, 2000a, 2000b; Straker, Mendelsohn, Moosa, & Tudin, 1996). For example, the Children’s Rights Development Unit (1994) has reported that 10% to 12% of the children in Northern Ireland have suffered from excess levels of stress because of the conflict. Whilst some reviews (e.g., Cairns & Wilson, 1989) and research (e.g., Joseph, Cairns, & McCollam, 1993) report little evidence that Northern Irish children have been psychologically affected by the political violence, Muldoon and Trew (2000a, 2000b) report that Northern Irish children’s experience of political conflict may be related to behavioural maladjustment. Indeed, Wilson and Cairns (1992) noted the possibility that aggressive behaviour may be a form of coping response for young people, particularly boys (see also Fee, 1980). This position is consistent with the view that experience of political conflict and violence is particularly, and perhaps causally, related to externalising and delinquent behaviour (Titmus, 1950; Shoham, 1994; Cairns, 1996). A major aim of the present research team is to determine the potential link between bullying behaviours in Northern Ireland’s schools and children’s experience of ‘The Troubles’. Research on Bullying in Northern Ireland Whilst there have been some exploratory studies of the nature of bullying within schools in Northern Ireland (e.g., Collins & Bell, 1996; Grant, 1996; Taylor, 1996), Bullying in Northern Ireland 6 the true prevalence and nature of the phenomenon in the Province has not yet been defined. The largest and most representative study to date in Northern Ireland has recently been published by the Department of Education for Northern Ireland (Collins, Mc Aleavey, & Adamson, 2002; Department of Education for Northern Ireland, 2001). Utilising The Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1989), the Department sampled 3,000 pupils from 120 schools in the Province (60 primary; 60 post-primary). Collins, et al. (2002) reported that 40.1% of primary students and 30.2% of post-primary students claimed to have been bullied during the period of the study (March 2000 - June 2000). The rate of victimization reported among the primary school pupils (40.1%) was higher than comparative rates reported for the Republic of Ireland (31.3%: O’Moore, Kirkham, & Smith, 1997) and England (37.0%: Whitney & Smith, 1993) using the same instrument. The victimization rate of 30.2% among post-primary pupils was similarly higher than those reported for the Republic of Ireland (15.6%: O’Moore, et al., 1997) and for England (14%: Whitney & Smith, 1993). Indeed, 5% of the primary pupils and 2% of the post-primary pupils reported that they had suffered bullying for several years. Regarding taking part in bullying others at school, this was reported by approximately a quarter (24.9%) of the primary pupils and 29% of the post-primary pupils. Whilst the rate of 24.9% for taking part in bullying others among the primary pupils was higher than the rate of 16% reported by Whitney and Smith (1993) in their English study, it was marginally lower than the 26.4% reported in O’Moore, et al.’s (1997) Irish study. The Northern Irish data regarding taking part in bullying others among the post-primary sample (29%) was significantly higher than the rates reported among both Irish (14.9%: O’Moore, et al., 1997) and English (7%: Whitney & Smith, 1993) samples. Collins et al. (2002) also asserted that all of the evidence indicated that bullying was happening Bullying in Northern Ireland 7 even in the best regulated schools, was not age or gender-specific, and was sometimes underplayed by the schools and teachers. Thus, it becomes evident that whilst the Republic of Ireland and England are close to Northern Ireland in terms of geography, there are significant differences in bullying and victimization rates across both the primary- and post-primary sectors that may be indicative of cultural differences between these jurisdictions. However, Collins, et al. (2002) caution us regarding direct comparisons between their data and that reported by O’Moore, et al. (1997) and Whitney and Smith (1993). Specifically, Collins, et al. (2002) report that their post-primary sample were aged 13- to 14-years whilst the age range in O’Moore, et al.’s (1997) sample was 11- to 18-years. Lower incidence figures reported by O’Moore, et al. (1997) may be a reflection of the larger age range of their sample and that bullying and victimization rates decrease with age. Collins, et al. (2002) also highlight that the data for the different studies were collected at disparate times (e.g., Northern Ireland data collected in 2000, English data collected in 1990). Whilst the recent Collins, et al. (2002) study has gone some way in highlighting the extent of bullying and victimization behaviours in the Northern Ireland school system, previous smaller scale studies (Collins & Bell, 1996; Grant, 1996; Taylor, 1996) have also helped to draw attention to the extent of such behaviours within the Province’s schools. For example, in their study among a sample of 118 (58 boys, 60 girls; age range = 8- to 10-years) pupils from 3 Belfast primary schools, Collins and Bell (1996) found that, on The Olweus Bully\Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1989), 24% (18% boys, 6% girls) of the pupils were identified as bullies (comparable figures for victims and bystanders were not reported). Also utilising The Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1989), Bullying in Northern Ireland 8 Taylor (1996) reports data from a study among a sample of 145 post-primary school pupils looking at the efficacy of Anti-Bullying Policies. Twenty-two per-cent of the pupils in schools with Anti-Bullying Policies reported being bullied compared with 31% in the control schools with no policy in place. In her study among 150 (82 boys, 68 girls) grade 6 primary school pupils, Grant (1996) found that, in response to the question: “Have you ever been bullied?” 59.33% (n = 89; 68% of boys, 49% of girls) of the pupils responded that they had been bullied. In interpreting this high rate, Grant (1996) asserted that it could reflect the fact that the pupils may have been “ … unsure where bullying began and ‘messing about’ ended.” (p. 37). Whilst the results from the studies by Collins and Bell (1996), Taylor (1996), and Grant (1996) add to our knowledge of the incidence of bullying and victimization in Northern Ireland’s school system, they should be interpreted with caution in that their relatively small samples make comparison with larger and more representative studies such as Collins, et al. (2002) difficult. Indeed, work by the current researchers aims to replicate the findings of Collins, et al. (2002) using The Olweus Bully\Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1989) and to further ascertain the incidence of bullying behaviours in the Northern Ireland school system utilising other instruments such as The Peer Relations Questionnaire (Rigby, 1998) and The Life in School Checklist (Arora, 1994). Action, Initiatives and Resource Materials Action aimed at preventing bullying in Northern Irelands schools has traditionally come from three areas: Government (Department of Education), local education authorities (Education and Library Boards) and the independent sector (night-classes, community drama groups). Bullying in Northern Ireland 9 At the Government level, anti-bullying initiatives and programmes have been developed and disseminated to the Provinces schools by the Department of Education. The focus of these publications (e.g., Promoting and Sustaining Good Behaviour: Discipline Strategy for Schools; Department of Education, 1998; Pastoral Care in Schools: Child Protection; Department of Education, 1999; Pastoral Care in Schools: Promoting Positive Behaviour; Department of Education, 2001) has sharpened as bullying becomes more of a topical issue in Northern Ireland. This is evidenced in the Education Minister’s plan to bring forward legislation to have every school develop and implement an Anti-Bullying Policy. Indeed, an examination of the Department of Education’s Pastoral Care publications (1999, 2001) demonstrates the increased attention being paid to school bullying by the Department. Whilst the 1999 publication deals with bullying in 1.5 pages of a total 118 pages, the 2001 publication offers a full chapter on bullying and developing an anti-bullying policy (26 pages of a total of 157 pages). Considering that the findings of the Department of Education study (Collins, et al., 2002) point out a high prevalence of bullying in the Province’s schools, and that the Education Minister is taking legislative steps regarding the issue, the production of guidelines to schools is welcome. At the level of local authority, some good guidance documents and support packs have been developed and made available to schools. For example, the Southern Education and Library Board have developed a set of easily scored questionnaires for pupils, parent or carer, teachers and ancillary staff that are freely available through the internet. The contents of the pack closely reflect the need for a whole-community approach to bullying in schools. In conjunction with the questionnaires, the Board also provides guidance documents and an example of an anti-bullying policy. In conjunction with the documentation from the Department of Education, this package Bullying in Northern Ireland 10 called ‘Challenging Bullying Behaviour’ appears to be a good start for schools whose aim to reduce bullying behaviours. The independent sector is also playing their part in addressing bullying. The authors have been involved over the last few years in the planning and delivery of night-classes specifically aimed at both the parents or carers of bullied children, and teachers and community workers. The response to the night-classes from teachers has been welcome and strategies for tackling bullying have been discussed and explored. An integral part of the night-classes has been the involvement of a local community theatre group (Balor Community Development Group) who perform their short play on school bullying. This play was also well received during a school bullying symposium at The British Psychological Society (Northern Ireland Branch) Annual Conference in 2000 (Lewis, 2000). After the play has finished (10 minutes duration), the audience are asked for strategies that ‘Jim’ or other actors in the play could have implemented to stop the bullying. When a strategy is offered, the person offering the strategy is encouraged to act it out with the actors ad-libbing around the new scenario. Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of these interactions is that those adults who offer strategies often see their futility when acted out. Future Directions As highlighted, Northern Ireland is a region in transition from a lengthy period of ethno-political conflict. As the impact of ‘The Troubles’ on children in the Province has not been fully researched or understood, detailed knowledge about school bullying may offer an insight to a previous unknown cost of the conflict. Preliminary data suggests that schoolchildren in Northern Ireland experience a greater level of bullying than children in most other countries. The current research programme Bullying in Northern Ireland 11 should aid policy developers and educators in Northern Ireland in their attempts to devise, implement, and evaluate evidence-based practices to reduce bullying in schools. Indeed, such an approach is required if impending legislation requires schools to have an anti-bullying policy. Whilst attempts are certainly being made to determine the true nature of bullying within a Northern Ireland context, future research should also focus on the experiences of minority groupings in the community, such as the traveller community and those children who are educationally disadvantaged. Also, focused in-service staff training that will further help all school staff in the identification and resolution of bullying behaviours will be welcomed. This, in conjunction with a committed approach of the whole community to reducing bullying will certainly help reduce the amount of bullying in Northern Irelands schools. Bullying in Northern Ireland 12 References ALSAKER, F., & BRUNNER, A. (1999) Switzerland. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 250-263. ARORA, T. (1994) Measuring bullying with the life in school checklist. Pastoral Care in Education, 12, 11-16. BJÖRKQVIST, K., & ÖSTERMAN, K. (1999) Finland. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 56-67. BYRNE, B. (1999) IRELAND. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 112-128. CAIRNS, E. (1996) Children and political violence. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell. CAIRNS, E., & DARBY, J. (1998) The conflict in Northern Ireland: causes, consequences and controls. American Psychologist, 53, 754-760. CAIRNS, E., & WILSON, R. (1989) Mental health aspects of political violence in Northern Ireland. International Journal of Mental Health, 18, 38-56. CHILDREN’S RIGHTS DEVELOPMENT UNIT (1994) UK agenda for children. London: CRDU. COLLINS, K., & BELL, R. (1996) Peer perceptions of aggression and bullying behaviour in primary schools in Northern Ireland. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 794, 77-79. COLLINS, K., Mc ALEAVEY, G., & ADAMSON, G. (2002) Bullying in schools: a Northern Ireland study. Research Report Series No.30. Bangor, N. Ire.: Department of Education for Northern Ireland. Bullying in Northern Ireland 13 DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION FOR NORTHERN IRELAND (1998) Promoting and sustaining good behaviour: a discipline strategy for schools. (Circular Number 1998/2). Bangor, N. Ire.: Department of Education for Northern Ireland. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION FOR NORTHERN IRELAND (1999) Pastoral care in schools: child protection. (Circular Number 1999/10). Bangor, N. Ire.: Department of Education for Northern Ireland. DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION FOR NORTHERN IRELAND (2001) Pastoral care in schools: promoting positive behaviour. (Circular Number 2001/10). Bangor, N. Ire.: Department of Education for Northern Ireland. DUEHOLM, N. (1999) Denmark. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a crossnational perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 49-55. FABRE-CORNALI, D., EMIN, J-C., & PAIN, J. (1999) France. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 128-139. FEE, F. (1980) Responses to a behavioural questionnaire of a group of Belfast children. In J. Harbison & J. Harbison (Eds.), A society under stress: children and young people in Northern Ireland. Somerset, England: Open Books. Pp. 3142. FONZI, A., GENTA, M. L., MENESINI, E., BACCHINI, D., BONINO, S., & COSTABILE, A. (1999) Italy. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a crossnational perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 140-156. Bullying in Northern Ireland 14 GRANT, M. (1996) Bullying: a review of the literature and results of a pilot study. Unpublished M.Sc. Thesis, Univ. of Ulster at Magee College, Londonderry, N. Ire. HARACHI, T. W., CATALANO, R. F., & HAWKINS, J. D. (1999a) Canada. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 296-306. HARACHI, T. W., CATALANO, R. F., & HAWKINS, J. D. (1999b) United States. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 279-295. JANOWSKI, A. (1999) Poland. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 264-275. JOSEPH, S., CAIRNS, E., & Mc COLLAM, P. (1993) Political violence, coping, and depressive symtomatology in Northern Irish children. Personality and Individual Differences, 15, 471-473. JUNGER-TAS, J. (1999) The Netherlands. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 205-223. LEWIS, C. A. (2000) Abstracts of the Northern Ireland Branch of the British Psychological Society Annual Conference 2000. Belfast, N. Ire.: British Psychological Society. Bullying in Northern Ireland 15 LÖSEL, F., & BLIESENER, T. (1999) Germany. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 224-249. MACKSOUD, M. S., & ABER, J. L. (1996) The war experiences and psychosocial development of children in Lebanon. Child Development, 67, 70-88. Mc AULEY, P. (1988) On the fringes of society: adults and children in a disadvantaged Belfast community. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Queen’s Univ. of Belfast. Mc GUCKIN, C., LEWIS, C. A. & SHEVLIN, M. (1999) Workplace bullying in health care settings: the role of the work environment and the psychological impact on personnel. The ‘Social Behaviour and Personality’ conference, Academy of Science, Brno, Cz Rep., October 1-3rd. Mc GUCKIN, C., LEWIS, C. A., & SHEVLIN, M. (2000a) The impact of workplace bullying on the self-esteem of nurses. Proceedings of the British Psychological Society, 9, 22. Mc GUCKIN, C., LEWIS C. A., SHEVLIN, M. (2000b) Towards a culture of respect and dignity in the workplace: a legal perspective from Northern Ireland. Minorities in a pluralist society at the turn of the millennium, Czech Academy of Science, Brno, Cz Rep., 1-3rd September. Mc GUCKIN, C., LEWIS, C. A., & SHEVLIN, M. (2000c) Workplace bullying: the role of the psychosocial work environment and current psychological well-being among mature students. Proceedings of The British Psychological Society, 9, 83-84. Bullying in Northern Ireland 16 Mc GUCKIN, C., LEWIS, C. A., & SHEVLIN, M. (2001a) Dignity in the workplace: the Northern Ireland experience. 10th European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology (EAWOP) Congress, Prague, Cz Rep., 14-16th May. Mc GUCKIN, C., LEWIS, C. A., & SHEVLIN, M. (2001b) The impact of workplace bullying on the self-esteem of nurses. 10th European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology (EAWOP) Congress, Prague, Cz Rep., 14-16th May. MELLOR, A. (1999) Scotland. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 91-111. MORITA, Y., SOEDA, H., SOEDA, K., & TAKI, M. (1999) Japan. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 309323. MULDOON, O., & TREW, K. (2000a) Children’s experiences and adjustment to political conflict in Northern Ireland. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 6, 157-176. MULDOON, O., & TREW, K. (2000b) Social group membership and perceptions of the self in Northern Irish children. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 24, 330-337. OHSAKO, T. (1999) The developing world. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective, London: Routledge. Pp. 359-375. OLWEUS, D. (1989) Bully/victim Questionnaire for Students. Bergen, Norway: Department of Psychology, Univ. of Bergen. Bullying in Northern Ireland 17 OLWEUS, D. (1999a) Norway. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective, London: Routledge. Pp. 28-48. OLWEUS, D. (1999b) Sweden. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 7-27. O’MOORE, A. M., KIRKHAM, C., & SMITH, M. (1997) Bullying behaviour in Irish schools: A nationwide study. Irish Journal of Psychology, 18, 141-169. ORTEGA, R., & MORA-MERCHAN, A. (1999) Spain. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 157-173. RIGBY, K. (1998) Manual for the Peer Relations Questionnaire. Point Lonsdale, Victoria, Australia: The Professional Reading Guide. RIGBY, K., & SLEE, P. T. (1999) Australia. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 324-339. SHOHAM, E. (1994) Family characteristics of delinquent youth in time of war. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 38, 247-258. SMITH, P. K. (1999) England and Wales. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a crossnational perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 68-90. SMITH, P. K., & MORITA, Y. (1999) Introduction. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 1-4. Bullying in Northern Ireland 18 SMITH, P. K., MORITA, Y., JUNGER-TAS, J., OLWEUS, D., CATALANO, R., & SLEE, P. (Eds.) (1999) The nature of school bullying: a cross national perspective. London: Routledge. STRAKER, G., MENDELSOHN, M., MOOSA, F., & TUDIN, P. (1996) Violent political contexts and the emotional concerns of Township youth. Child Development, 67, 46-54. SULLIVAN, K. (1999) Aotearoa/New Zealand. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. JungerTas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective, London: Routledge. Pp. 340-355. TAYLOR, A. (1996) Comparison study of bullying rates in three schools with antibullying programmes and three control schools with no anti-bullying programmes in Northern Ireland. Unpublished M.Sc. Applied Psychology thesis, Univ. of Ulster at Jordanstown, Belfast, N. Ire. TITMUS, R. M. (1950) Problems of Social Policy. London: HMSO. TOMÁS DE ALMEIDA, A. M. (1999) Portugal. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. JungerTas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 174-186. VETTENBURG, N. (1999) Belgium. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a crossnational perspective. London: Routledge. Pp. 187-204. WHITNEY, I., & SMITH, P.K. (1993) A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educational Research, 35, 3-25. WILSON, R., & CAIRNS, E. (1992) Trouble, stress and psychological disorder in Northern Ireland. The Psychologist, 5, 347-350.