Precis of the Fifth Meditation (The Essence of Material Things

advertisement

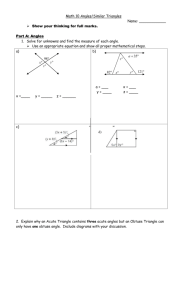

Précis of the Fifth Meditation (The Essence of Material Things. Another Discussion of God’s Existence) 1. He will return to the attributes of God and his own nature but first wishes to address whether there is any certainty to be had about material things. 2. Before considering whether such things exist outside his own mind, what he wants to do initially is to clear up the ideas he has about them. 3. What is very clear is that Descartes has a distinct image of extension: length, breadth and depth. He can also pick out other things from this extension: size; shape; position; motions; duration in time. These simple qualities [which can also be expressed mathematically] occur so naturally to the mind that it is almost as if they have always been there, waiting to be discovered. 4. But first, he draws attention to the fact that the ideas he has are not nothing. Another thing about these ideas is that they have true and immutable natures. His example is a triangle: he is certain that it has three sides and three angles; that the three angles are equal to two right-angles; that the largest angle is opposite the longest side; and so on to other geometric proofs. He knows these proofs through recognition of this nature rather than inventing them himself. 5. Could he have got the thought of the triangle through his senses? He rejects this possibility on the grounds that he can conceive of an infinite number of different triangles (in principle), as well as other geometric figures – and he hasn’t seen anywhere near such a quantity. Also, he can find proofs about all of them and these proofs are true which makes them a something rather than a nothing. Furthermore, he sees these proofs ‘clearly and distinctly’ so cannot help regarding them as true. This knowledge fits neatly with his previous idea of arithmetic and geometry being among the constant truths. 6. From this sort of thinking he can provide another proof of God’s existence. If he can get to the truth about triangles from his thoughts of them (using ‘clear and distinct’ perception as his criterion for truth) he can get to the truth of God’s existence from his idea of Him. The existence of God cannot be separated from the essence of God any more than the sum of the three angles in a triangle can be separated from the essence of a triangle. A supremely perfect being which does not exist is less perfect than one that does. Since Descartes has such a supremely perfect being in mind then, if it is perfect (which it is) then it must exist. 7. He acknowledges that this just seems too good to be true. Besides, he can separate the essence from the existence in other things, so why not the same separation for God? He claims that it is clear that separating existence from God’s essence is as impossible as separating the fact of the internal angles of a triangle adding up to two right angles from the essence of a triangle. Existence is a perfection and God, the sum of all perfections, necessarily possesses it. 8. He does acknowledge that just because he can think of something, this does not mean that it necessarily exists: he can think of a winged horse but this does not entail the existence of a winged horse. Is his thought of God like this? 9. Such a question points to a mistake of logic. His point is that a God without existence is a contradiction and is hence strictly inconceivable, he is not free to conceive of such a thing in the same way he can conceive of a winged horse. It would be as inconceivable to try to think of a triangle whose internal angles did not equal two right angles. 10. Here, Descartes struggles to dismiss any accusation that his argument is circular, that is: God exists and has given him clear and distinct perception of the truth; his clear and distinct perception of the truth tells him God exists. He argues that just as he might not have thought of the truths about a triangle when one first floated into his mind, so he might not have apprehended the truths about God when that concept first floated into his mind. But, after due consideration, he came to know the proofs about triangles. Likewise, after due consideration, he came to know the qualities of God which were innate in him. And one of these is that he is a supremely perfect being and hence must exist. Confirmation of this idea of God comes in the following: a) only God has an essence which includes existence; b) since having more than one such God is incomprehensible, this means God has always, and will always, exist; c) he cannot comprehend changing or diminishing any of God’s attributes. 11. Whatever arguments he uses, they all are grounded on the following: he is convinced that something is true only when he perceives it clearly and distinctly as in the proof about triangles. Nothing could be clearer than the existence of God. He notes that the certainty about all other truths depends on this one being true. 12. Although his nature tempts him to stray from the truth derived from his understanding of his own mind, God is a guarantor of truth. Without him, Descartes would be left with what are ‘merely unstable and changeable opinions’ and even his knowledge of geometrical proofs (without God) is open to the scepticism of where such knowledge derives from [the evil demon is a possibility if God does not exist]. 13. Knowing that God exists, and that all depends on God, and that God is not a deceiver, and that God will not allow him to be deceived when he perceives something clearly and distinctly, Descartes can relax: he can be sure that his knowledge is true. Even if all this is a dream, his knowledge of God and geometry are unassailable. 14. Certainty depends on God’s existence: He is an epistemological necessity. Descartes is assured of knowledge about many intellectual things (things of the mind alone) and about those ideas he has which can be described mathematically (his simple elements which are essential to the idea of material objects).