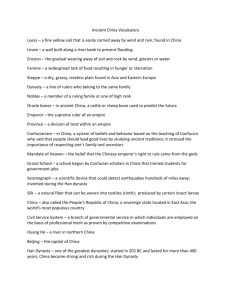

An outline of the Traditional Chinese Culture

advertisement