Cleopatra and her impact on Roman politics

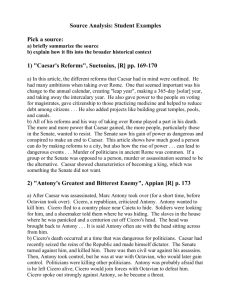

advertisement