Latin America and the Caribbean in the Age of Revolution

advertisement

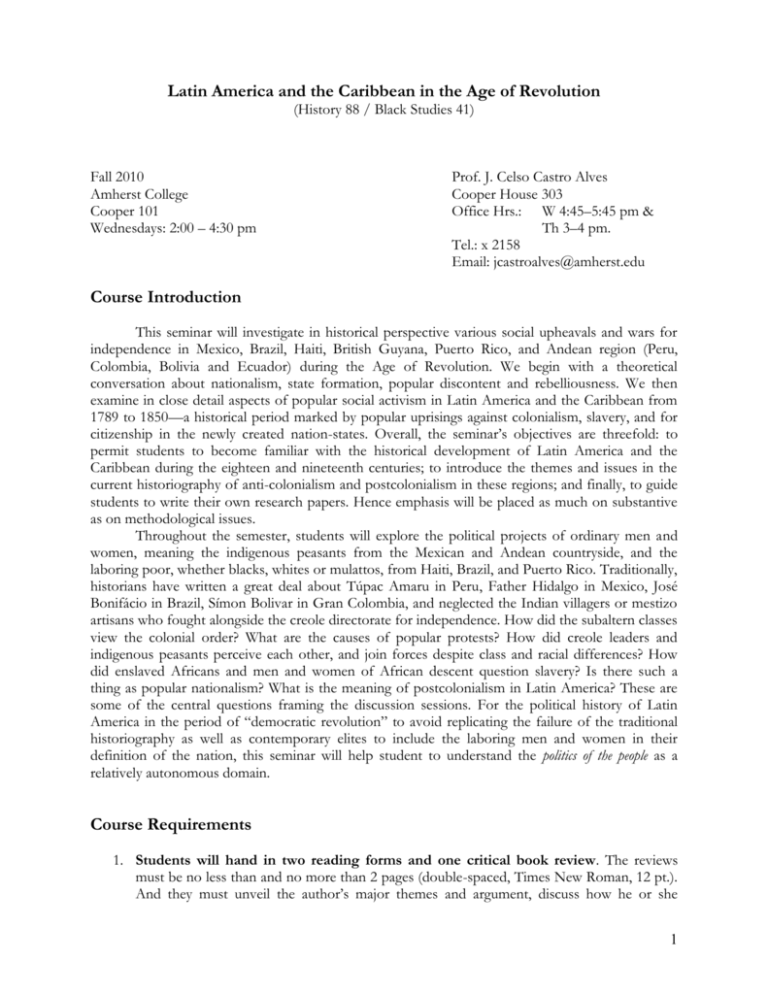

Latin America and the Caribbean in the Age of Revolution (History 88 / Black Studies 41) Fall 2010 Amherst College Cooper 101 Wednesdays: 2:00 – 4:30 pm Prof. J. Celso Castro Alves Cooper House 303 Office Hrs.: W 4:45–5:45 pm & Th 3–4 pm. Tel.: x 2158 Email: jcastroalves@amherst.edu Course Introduction This seminar will investigate in historical perspective various social upheavals and wars for independence in Mexico, Brazil, Haiti, British Guyana, Puerto Rico, and Andean region (Peru, Colombia, Bolivia and Ecuador) during the Age of Revolution. We begin with a theoretical conversation about nationalism, state formation, popular discontent and rebelliousness. We then examine in close detail aspects of popular social activism in Latin America and the Caribbean from 1789 to 1850—a historical period marked by popular uprisings against colonialism, slavery, and for citizenship in the newly created nation-states. Overall, the seminar’s objectives are threefold: to permit students to become familiar with the historical development of Latin America and the Caribbean during the eighteen and nineteenth centuries; to introduce the themes and issues in the current historiography of anti-colonialism and postcolonialism in these regions; and finally, to guide students to write their own research papers. Hence emphasis will be placed as much on substantive as on methodological issues. Throughout the semester, students will explore the political projects of ordinary men and women, meaning the indigenous peasants from the Mexican and Andean countryside, and the laboring poor, whether blacks, whites or mulattos, from Haiti, Brazil, and Puerto Rico. Traditionally, historians have written a great deal about Túpac Amaru in Peru, Father Hidalgo in Mexico, José Bonifácio in Brazil, Símon Bolivar in Gran Colombia, and neglected the Indian villagers or mestizo artisans who fought alongside the creole directorate for independence. How did the subaltern classes view the colonial order? What are the causes of popular protests? How did creole leaders and indigenous peasants perceive each other, and join forces despite class and racial differences? How did enslaved Africans and men and women of African descent question slavery? Is there such a thing as popular nationalism? What is the meaning of postcolonialism in Latin America? These are some of the central questions framing the discussion sessions. For the political history of Latin America in the period of “democratic revolution” to avoid replicating the failure of the traditional historiography as well as contemporary elites to include the laboring men and women in their definition of the nation, this seminar will help student to understand the politics of the people as a relatively autonomous domain. Course Requirements 1. Students will hand in two reading forms and one critical book review. The reviews must be no less than and no more than 2 pages (double-spaced, Times New Roman, 12 pt.). And they must unveil the author’s major themes and argument, discuss how he or she 1 handles historical evidence, whether the author proves his or her argument, and assess the book’s overall contribution to the field. (20% of the final grade) 2. Each seminar session will end with student presentations of primary sources (10–15 minutes). (10% of the final grade) 3. I expect students not to coast through seminars but contribute actively to each discussion. Evaluation of student participation will be based on the following criteria: 1. Active listening and engagement in class debates or dialogues; 2. Students’ command of the material (methodologies, theoretical framework, and historical events) in the readings; 3. Attendance. Failure to attend class and film screenings will be reflected in participation grades. Students will be granted permission to miss class only in cases of illness and family emergencies. (30% of the final grade) 4. Students will write a research paper of 20–25 pages, double-spaced, and printed preferably in Times New Roman, 12 pt., and based on original library or archival research. Intermediate written assignments will include preliminary bibliography, an outline and final bibliography, and a draft of the research paper. In order to compile the bibliography for your final assignment, you need to: 1. Search the library catalogue using keywords and subject searches. 2. Browse the library shelves. 3. Follow up references in the footnotes and bibliographies of books and articles you have read for the course. 4. Search databases such as JSTOR, Historical Abstracts, and Academic Search Premier for articles. (40% of the final grade) Late Assignments: Students are responsible for handing in all assignments on time. Extensions will be granted only in circumstances involving illness and family emergencies. When late with papers, students will lose half of a letter grade per day. Papers handed in more than seven days late will receive a failing grade. Required Books All books are available at Amherst Books (8 Main Street, Amherst) and are on reserve at the Frost Library. Jeremy Adelman, Sovereignty and Revolution in the Iberian Atlantic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). Matt D. Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2006). Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004). Brooke Larson, Trials of Nation Making: Liberalism, Race, and Ethnicity in the Andes, 1810–1910 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). Kenneth Maxwell, Conflicts and Conspiracies: Brazil and Portugal, 1750–1808, rev. ed. (New York: Routledge, 2004). James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990). 2 Sinclair Thomson, We Alone Will Rule: Native Andean Politics in the Age of Insurgency (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 2002). Background Readings (not required) Christon I. Ancher, ed., The Wars of Independence in Spanish America (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Books, 2000). Leslie Bethell, ed., The Independence of Latin America (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987). Richard Graham, Independence of Latin America: A Comparative Approach (New York: Alfred A. Knoft, 1972). Brian R. Hamnett, “Process and Pattern: A Re-Examination of the Ibero-American Independence Movements, 1808–1826,” Journal of Latin American Studies 29, no. 2 (1997): 279–328. Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution, 1789–1848 (New York: Vintage Books, 1996). Lesler D. Langley, The Americas in the Age of Revolution, 1750–1850 (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1996). John Lynch, The Spanish Revolutions, 1808–1826, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1986). John Lynch, Latin America Between Colony and Nation: Selected Essays (New York: Palgrave, 2001). Anthony McFarlane and Eduardo Posada Carbo, eds., Independence and Revolution in Spanish America: Perspectives and Problems (London: Institute for Latin American Studies, University of London, 1999). Jaime E. Rodriguez O., The Independence of Spanish America (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998). Victor M. Uribe-Uran, ed., State and Society in Spanish America During the Age of Revolution (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Books, 2001). Books on Reading & Writing (not required but recommended) George Plimpton: How much rewriting do you do? Ernest Hemingway: It depends. I rewrote the ending of Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, thirty-nine times before I was satisfied. Plimpton: Was there some technical problem there? What was it that had stumped you? Hemingway: Getting the words right. Ernest Hemingway interviewed by George Plimpton, The Paris Review 18 (1958). Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren, How to Read a Book, rev. ed. (New York: Touchstone Book, 1972). Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams, The Craft of Research (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1995). Claire Kehrwald Cook, Line by Line: How to Edit Your Own Writing (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985). Richard A. Lanham, Revising Prose (New York: Longman, 2007). Nancy Lane, Margaret Chisholm, Carolyn Mateer, Techniques for Student Research: A Comprehensive Guide to Using the Library (New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers, 2000). John R Trimble, Writing with Style: Conversations on the Art of Writing (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975). William Zinsser, On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction, rev. ed. (New York: Collins, 2006). 3 Course Outline & Readings Week I: Introduction (Sept. 15) Week II: Conceptualizing the Age of Revolution (Sept. 22) Jeremy Adelman, Sovereignty and Revolution in the Iberian Atlantic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). Optional Readings: Lesler D. Langley, The Americas in the Age of Revolution, 1750–1850 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996). R. R. Palmer, The Age of Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760–1800, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1958–1964). Brian R. Hamnett, “Process and Pattern: A Re-Examination of the Ibero-American Independence Movements, 1808–1826,” Journal of Latin American Studies 29, no. 2 (1997):279–328. Week III: Theoretical Considerations I—Defining the Subaltern (Sept. 29) James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990). Optional Readings: Fernando Coronil, “Listening to the Subaltern: The Poetics of Neocolonial States,” Poetics Today 15 no. 4 (1994). Ranajit Guha, “On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India,” Subaltern Studies I: Writings on South Asian History and Society, 4th ed. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), 1–8. E. P. Thompson, preface to The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage, 1963). Week IV: Conspiracies in Late Colonial Brazil (Oct. 6) Kenneth Maxwell, Conflicts and Conspiracies: Brazil and Portugal, 1750–1808, rev. ed. (New York: Routledge, 2004). Optional Readings: Roderick J. Barman, Brazil: The Forging of a Nation, 1798–1852 (California: Stanford Univ. Press, 1988). Leslie Bethell, ed. Brazil: Empire and Republic, 1822–1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989). 4 Leslie Bethell, From Independence to c. 1870, vol. III of The Cambridge History of Latin America (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1985). Emilia Viotti da Costa, The Brazilian Empire: Myths and Histories, rev. ed. (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2000). Richard Graham, “Constructing a Nation in Nineteenth-Century Brazil: Old and New Views on Class, Culture, and the State,” Journal of the Historical Society 1, no. 2/3 (2001). Kenneth Maxwell, Pombal: Paradox of the Enlightenment (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995). Kirsten Schultz, Tropical Versailles: Empire, Monarchy, and the Portuguese Royal Court in Rio de Janeiro, 1808–1821 (New York: Routledge, 2001). Reading Form Due (Group A) Week V: The Age of Andean Insurrection (Oct. 13) Sinclair Thomson, We Alone Will Rule: Native Andean Politics in the Age of Insurgency (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002). Optional Readings: Steve J. Stern, ed., Resistance, Rebellion, and Consciousness in the Andean Peasant World, 18th to 20th Centuries (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988). Charles F. Walker, Smoldering Ashes: Cuzco and the Creation of Republican Peru, 1780-1840 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999). Reading Form Due (Group B) Week VI: Theoretical Considerations II: Becoming National (Oct. 20) Benedict Anderson, “Introduction,” “Cultural Roots,” “The Origins of National Consciousness,” and “Creole Pioneers,” in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 1991), 1–65. [Online] François-Xavier Guerra, “Forms of Communication, Political Spaces, and Cultural Identities in the Creation of Spanish American Nations,” in Beyond Imagined Communities: Reading and Writing the Nation in Nineteenth-Century Latin America, edited by Sara Castro-Klarén and John Charles Chasteen (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2003), 3–32. [Online] Tulio Halperín Donghi, “Argentine Counterpoint: Rise of the Nation, Rise of the State,” in Beyond Imagined Communities, 33–53. [Online] Sarah C. Chambers, “Letters and Salons: Women Reading and Writing the Nation,” in Beyond Imagined Communities, 54–83. [Online] Optional Reading: 5 Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny, eds., Becoming National: A Reader (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996). Oral Presentation of Final Research Project Week VII: The Haitian Revolution (Oct. 27) Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2004). Optional Reading: Susan Buck-Morse, Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009). Laurent Dubois and John D. Garrigus, Slave Revolution in the Caribbean, 1789_1804: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2006) Eugene D. Genovese, “The Turning Point,” in From Rebellion to Revolution Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the New World (New York: Vintage, 1979), 82–125. C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’ Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, 2nd ed. (New York: Vintage, 1989). Toussaint L’Ouverture, The Haitian Revolution (New York: Verso, 2008). Nick Nesbitt, Universal Emancipation: The Haitian Revolution and the Radical Enlightenment (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008) Ashli White, Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010). Reading Form Due (Group A) Week VIII: The Haitian Revolution in Cuba & Across the Atlantic Ocean (Nov. 03) Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “The Unthinkable History,” in Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 70–107. [Online] Matt D. Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2006). Optional Reading: David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). David Geggus, “The Influence of the Haitian Revolution on Blacks in Latin America and the Caribbean,” in Blacks, Coloureds and National Identity in Nineteenth–Century Latin America, edited by Nancy Priscilla Naro (London: Institute of Latin American Studies, 2003), 38–59. David Patrick Geggus, “Slavery, War, and Revolution in the Greater Caribbean, 1789–1815,” in A Turbulent Time: The French Revolution and the Greater Caribbean, edited by David Barry Gaspar and David Patrick Geggus (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1997), 1–50. David Patrick Geggus and Norman Fiering, eds., The World of the Haitian Revolution (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009). 6 Jane G. Landers, Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010) Robert L. Paquette, “Social History Update: Slave Resistance and Social History,” Journal of Social History 24, no. 3 (1991):681–85. Robert L. Paquette, Sugar Is Made With Blood: The Conspiracy of La Escalera and the Conflict between Empires over Slavery in Cuba (Middletown, C.T.: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1988). Reading Form Due (Group B) Friday, November 5: Two-page Description of Final Project and Bibliography Due. Students need to hand in two pages describing their final projects (topic, methodology, and argument), and a selected bibliography listing primary and secondary sources. Week IX: Defining Race in the Age of Revolution (Nov. 10) Barbara J. Fields, “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America,” New Left Review 181 (1990):95–118. [Online–Frost Library] Marixa Lasso, “Race War and Nation in Caribbean Gran Colombia, Cartagena, 1810–1832,” American Historical Review 111, no. 2 (2006). [Online–Frost Library] Aline Helg, “Simón Bolívar and the Spectre of Pardocracia: José Padilla in Post-Independence Cartagena,” Journal of Latin American Studies 35 (2003):447–471. [Online–Frost Library] Optional Readings: Nicholas Canny and Anthony Pagden, eds., Colonial Identity in the Atlantic Word, 1500–1800 (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1987). Aline Helg, Liberty & Equality in the Caribbean Colombia, 1770–1835 (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2004). Hendrik Kraay, Race, State and Armed Forces in Independence-Era Brazil: Bahia, 1790’s–1840’s (Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 2001). Week X: Slave Revolts in the Age of Revolution (Nov. 17) Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994). Critical Book Review Due (All) Thanksgiving, November 20–28 Week XI: Subaltern Politics in Mexico and Puerto Rico (Dec. 01) 7 John Tutino, “The Revolution in Mexican Independence: Insurgency and the Renegotiation of Property, Production, and Patriarchy in the Bajío, 1800–1855,” Hispanic American Historical Review 78, no. 3 (1998): 367–418. [Online– JStor, Frost Library] Eric Van Young, “Millennium on the Northern Marches: The Mad Messiah of Durango and Popular Rebellion in México, 1800–1815,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 28, no. 3 (1986):385–413. [Online–JStor, Frost Library] Francisco A. Scarano, “The Jíbaro Masquerade and the Subaltern Politics of Creole Identity Formation in Puerto Rico, 1745–1823,” American Historical Review 101, no. 5 (1996):1398–1431. [Online– JStor, Frost Library] Optional Reading: Peter Guardino, The Time of Liberty: Popular Political Culture in Oaxaca, 1750–1850 (Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 2005). Week XII: Postcolonial Transitions (Dec. 08) Brooke Larson, Trials of Nation Making: Liberalism, Race, and Ethnicity in the Andes, 1810–1910 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). Optional Readings: Bushnell, David. Reform and Reaction in the Platine Provinces, 1810–1852 (Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1983). Cecília Mendez G., The Plebeian Republic: The Huanta Rebellion and The Making of The Peruvian State, 1820–1850 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005). Mark Turner and Andrés Guerrero, eds., After Spanish Rule: Postcolonial Predicaments of the Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003). Mark Turner, “’Republicanos’ and ‘La Comunidad de Peruanos’: Unimagined Political Communities in Postcolonial Andean Peru,” Journal of Latin American Studies 27, no. 2 (1995):291–318. Friday, December 10: Draft of Research Paper Due. Students should have between 10 and 15 pages of their final research paper done by this date and handed in before 11 am. Week XIII: Final Thoughts and Discussion of Research Papers (Dec. 11–13) Wednesday, December 18, 2007: Final Research Paper Due [Please email your essay to Jcastroalves@amherst.edu before 5 pm] 8 Sample of the Reading Form Name: Latin America and the Caribbean in the Age of Revolution Reading Form Date: Book (author/title/publisher/date): Pre-reading: 1. What does the title tell you about the book? 2. Do you know anything about the author? (What? Is he or she a historian? A social historian? Labor? Cultural?) 3. Does the design on the cover tell you anything about the book? What? 4. How is the book organized? Do the names of the chapters tell you anything? Is there a logic connecting the chapters? What is it? Does a particular chapter look like it might be the most important? (please look carefully at the table of contents) Analytical Reading: 5. What is the book’s (or essay’s) central question? (What problem is the author trying to solve?) 6. Name three terms that are indispensable to the meaning of the book or essay and define them (You need to find the central words/concepts which the author has defined in new ways). 7. Please state three propositions that are central to the argument. (Propositions are sub-arguments. To believe the larger argument, you need to believe the sub-arguments. Locate the important sentences and use them to name the main propositions). 8. Please state the main argument as briefly as possible. Does the author state the argument? Where? 9. Name the three most compelling pieces of proof the author uses to support his thesis. (Here you should cite specific facts or incidents, not arguments or general propositions) 10. Quote three phrases that are crucial to the meaning of the book and give their location in the text. (Here you should choose the most outstanding phrases, the ones that come closest to making you want to memorize them.) Critical Reading: 11. What do you find most and/or least convincing about this book? Why? 12. What does this specific book tell us about the “Age of Revolution”? How does the book help us to refine our methodological approach to the period stretching from 1750 to 1850? [Adapted from the Black Studies 11 Reading Form, Amherst College] 9 Sample of the Grading Form (Book Review & Final Research Essay) Student Grade _______ Response to Specific Questions: Topic and argument _______________________________ Critical use/discussion of historical evidence ___________________________________ Engagement with historical debates ___________________________________ Length of essay _______________ Commend Well-stated arguments _________________ Suggest Need deeper analysis/sharper focus _____________________________ Effective examples _____________________ Need more examples _________________ Good use of specific detail _______________ Need more detail ____________________ Good logic ___________________________ Check contradictions _________________ Well-structured/organized _______________ Rethink organization _________________ Clear/well-written ______________________ Syntax needs attention ________________ Good command of topic/comprehension ____ Problems with comprehension __________ ____________________________________ Bibliographic/footnote presentation ________ Cite sources/problems with bibliographic format _____________________________ Additional Comments: [Adapted from Robert E. Weir, AHA, 1993] 10