Special Education Policy Issues in Washington State

advertisement

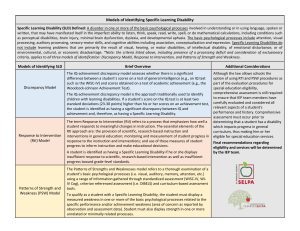

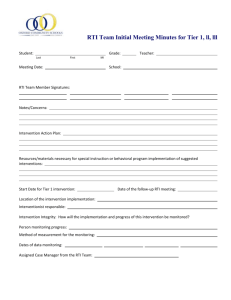

Special Education Law Quarterly July 2007 Bulletin #10 IDENTIFYING AND DELIVERING EDUCATIONAL SERVICES TO STUDENTS WITH SPECIFIC LEARNING DISABILITIES: NEW REQUIREMENTS IN IDEA 2004 I. Introduction The United States Congress reauthorized the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (hereafter IDEA) in December 2004. The changes made to the statute were substantial. Most amendments were effective in July 2006 despite the fact that the federal Department of Education (DOE) regulations that further explain and guide implementation of the statutory changes were not issued until September 2006. In addition to the federal law, the Washington State Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) has recently released the revised state regulations—the Washington Administrative Code (WACs)—that align the state law with the IDEA 2004. These state regulations become effective at the end of July 2007 and will guide the day-to-day provision of special education services in Washington. This Bulletin focuses only on the changes in IDEA 2004 that relate to students with learning disabilities. Specifically, the Bulletin covers the amendments regarding identifying children with specific learning disabilities (SLD), early intervening services (EIS), and Response to Intervention (RTI) and how they relate to service delivery for students with learning disabilities. For those readers interested in a comprehensive review of the IDEA 2004 changes, please see the resources listed at the end of this Bulletin. And to review the revised Washington State regulations, check online at: http://www.k12.wa.us/SpecialEd/default.aspx Page 2 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 II. Who is a Student with Learning Disabilities under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) 2004? Any review of special education services relevant to students with learning disabilities requires a discussion of how we define “learning disabilities.” Even if we—educators—can agree on the need for specialized interventions for students with learning disabilities, how do we decide who is in the group? Defining “disability” generally is difficult and much debated in the other laws addressing rights to education for students with disabilities such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504) and our Washington State Law Against Discrimination.1 Nonetheless, it is generally easier to understand functional limitations related to physical impairments—such as low vision, deafness, or the inability to walk—then it is to identify and label a functional difference or limitation that is invisible such as a learning disability. It is not only politicians and lawyers (who create the laws) who have disagreed over the years about who should be labeled “learning disabled” but also medical professionals and educators.2 There has generally been agreement, however, that an individual who demonstrates a severe discrepancy between his/her academic ability and achievement has a learning disability. If nothing else, this discrepancy model provided some objective measure that educators could rely upon for determining eligibility under IDEA. And the model took into account the fact that some students with very high academic potential (as generally measured with an IQ test) could demonstrate a low achievement on reading and other diagnostic tests due to a learning disability. The discrepancy model is not the only way to measure a learning disability, however, and the IDEA 2004 emphasizes alternative methods. Although IDEA allows states to continue to use the discrepancy model, it does not allow states to require that it be used by local districts. In other words, a discrepancy model at most can be available as an optional method of determining eligibility for IDEA services on the basis of a learning disability. The IDEA now recommends that districts’ assess a student’s response to “high-quality general education instruction” as the method for determining the presence of a learning disability. Therefore, educators must ensure that a student experiencing difficulties is receiving high quality instruction, collect data on the student’s response and assess his/her response to this intervention prior to labeling the child as “learning disabled.” Like No Child Left Behind and the recent narrowing of the definition of “disability” under the federal nondiscrimination laws mentioned earlier (and arguably the Washington Law Against Discrimination also), IDEA 2004 encourages states to serve students with learning difficulties within the general education system first, before determining that they are eligible for IDEA. A. Learning Disability Eligibility under Federal and State Law Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 Page 3 of 15 The place to start in reviewing the new federal requirements for determining eligibility for special education services under the category of “learning disability” as well as the Washington State regulations, is determining how the respective laws define learning disability. Although it is common to use and hear the phrase “learning disability” to describe students who are underachieving academically, the federal and state laws use the phrase “specific learning disability” to describe the group of students who are eligible for IDEA services. This Bulletin uses the legal definition of “specific learning disability” or SLD, but both phrases are used interchangeably in practice. 1. Specific Learning Disability Defined The IDEA 2004 regulations define “specific learning disability” as follows: i) General. Specific learning disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. ii) Disorders not included. Specific learning disability does not include learning problems that are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of mental retardation, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage.3 Washington State special education draft regulations follow the federal IDEA terminology and define “specific learning disability” as follows: (k)(i) Specific learning disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia, that adversely affects a student's educational performance. (ii) Specific learning disability does not include learning problems that are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of mental retardation, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage.4 Although these definitions are quite comprehensive—covering both what is and what is not a specific learning disability for purposes of special education eligibility—the quantity of the functional limitation or problem required to qualify is not included. Therefore, to determine actual eligibility, additional determinations are required. Meeting the IDEA definition is only the beginning of the process; the additional considerations required are described below. Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Page 4 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 2. Eligibility Determination As mentioned above, Local Education Agencies (LEAs) are not required under the IDEA 2004 to use severe discrepancy models which focus on the difference between a child’s ability and achievement to determine eligibility for IDEA services.5 They are, however, authorized under the new law to use “a child’s response to scientific, research-based intervention,” commonly referred to as Response to Intervention or RTI, as part of their evaluation procedure.6 The DOE regulations expand on this statutory language by requiring that states adopt criteria consistent with the regulations regarding eligibility and (1) must not require use of severe discrepancy analysis (intellectual ability compared to academic achievement), but (2) must use a process based on child's response to scientific, research-based intervention, and (3) may permit use of other alternative research-based procedures as defined in [another section of the law].7 Additional procedures for identifying children with specific learning disabilities are found in the DOE regulations to IDEA. First, the IDEA 2004 requires school districts to add members to the team of qualified professionals who will determine eligibility. Specifically, the decision must be made by the child’s parents and the child's regular education teacher or, if the child does not have a regular education teacher, a regular education teacher qualified to teach a child of that age or an individual qualified to teach a child of less than school age and at least one person qualified to conduct individual diagnostic examinations—e.g., a school psychologist, speech-language pathologist or remedial reading teacher.8 To determine the existence of a specific learning disability, the eligibility group must show that the child: (1) does not achieve adequately for age or meet State-approved grade-level standards when provided with learning experiences/instruction appropriate for age or Stateapproved grade level standards in one of 8 areas (oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skill, reading fluency, reading comprehension, mathematics calculations, mathematics problem-solving); (2) does not make sufficient progress to meet age or State-approved grade-level standards in one of 8 areas when using process based on child's responses to scientific, research-based intervention; or exhibits pattern of strengths and weaknesses in performance, achievement, or both, relative to age, State-approved grade-level standards, or intellectual development, determined by group to be relevant to identification of specific learning disability; and (3) findings are not primarily result (italics added) of other factors (visual, hearing, motor disability; mental retardation; emotional disturbance; cultural factors; environmental or economic disadvantage; limited English proficiency).9 Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 Page 5 of 15 The inclusion of the phrase highlighted above, not primarily the result, suggests that influence from these other factors is allowed in the eligibility determination rather than the factors being mutually exclusive. IDEA 2004 attempts to replace the discrepancy analysis with a standard that arguably is a more inclusive way to determine SLD in some children. For example, the new standard could qualify students who previously did not meet the required discrepancy. An example would a very low achieving student who also tested in the low range intellectually and thus did not qualify under a discrepancy analysis because there was no discrepancy between ability and achievement. On the other hand, the new standard also could exclude students who are very "bright" and only achieving academically at average or above average levels but not at their academic potential. Although too soon to assess how these changes will actually affect a student’s eligibility, in some ways the new standard provides professionals greater flexibility but without the "bright-line" decision-making guidelines under discrepancy analysis. The new IDEA regulations also require that educators ensure that a student’s underachievement is not due to lack of appropriate instruction in reading or math. In order to satisfy this requirement, the teams must consider: (1) whether scientifically-based data demonstrates that prior to or as part of the referral process, the student was provided with appropriate instruction in a regular education setting delivered by qualified personnel and (2) data-based documentation of repeated assessments at reasonable intervals, reflecting formal assessment of student progress during instruction. It is important to note that not only must this information be provided to parents,10 but that parents continue to have their notice and consent rights to any evaluation of their child for special education services. As implied above, and stated clearly elsewhere, the IDEA 2004 regulations now require that educators determine eligibility after observing the student. Specifically, the regulations require that the child is observed in the regular learning environment by someone other than the child’s teacher in order to document academic performance and behavior in areas of difficulty. The educators must decide to use information from observation in routine classroom instruction and monitoring before referral for evaluation or at least one member must conduct observation of academic performance in the regular classroom after referral for an evaluation and obtaining parental consent.11 If the child is out of school or less than school age, the district must observe the child in the environment appropriate for his/her age. Finally, the special education law requires that the determination of eligibility must be documented in detail by the group. Specifically, the federal regulations require a statement that includes the following components: (1) whether the child has a specific learning disability; (2) the basis for making the determination; Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Page 6 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 (3) relevant behavior noted during observation and the relationship of behavior to academic functioning; (4) educationally relevant medical findings, if any; (5) whether the child, (i) does not achieve adequately for age or to meet State-approved standards and (ii) does not make sufficient progress to meet age or State approved grade-level standards or exhibits pattern or strengths and weaknesses in performance; (6) effects of other factors (visual, hearing, motor disability; mental retardation; emotional disturbance; cultural factors; environmental or economic disadvantage; limited English proficiency) on achievement level; and (7) if the child participated in process which assesses response to scientific, researchbased intervention, (i) instructional strategies used and student data collected and (ii) documentation of parent notification about a) the State's policies about amount and nature of student performance data collected and general education services provided, 2) the strategies for increasing child's rate of learning, and 3) parent's right to request an evaluation.12 The language above that requires data documentation and instruction based on scientific, research-based interventions is one example of the incorporation of many of the core concepts of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in the reauthorized IDEA. A final eligibility requirement in IDEA 2004 concerns the documentation of the professional judgments of the group members. The law requires that each group member must certify in writing whether the eligibility report reflects that member's conclusion; if not, then the member must submit a separate statement presenting his or her conclusions. Although it is not unheard of for special educators to write separate “minority reports” that differed from the multidisciplinary team conclusions, this has not been a common practice and teams tend to work out any disagreement over eligibility and/or Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) content. It will be interesting to see if the new SLD eligibility regulations change the past practice and make minority reporting more common. The previous Washington Administrative Code (WAC) used the discrepancy model as the method to identify children with SLDs.13 The new WACs change the state regulations to follow the changes in IDEA 2004. The WACs state that schools may now a use severe discrepancy model, a RTI, or a combination of both to determine if a student with a SLD is eligible for special education—i.e., they allow what the federal law allows. The regulation reads as follows: In addition to the evaluation procedures for determining whether students are eligible for special education, school districts must follow additional procedures for identifying whether a student has a specific learning disability. Each school district shall develop procedures for the identification of students with specific learning disabilities which may include the use of: Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 Page 7 of 15 (1) A severe discrepancy between intellectual ability and achievement; or (2) A process based on the student's response to scientific, research-based intervention; or (3) A combination of both.14 Relevant sections of the WACs dealing with the evaluation group, determination of learning disability eligibility, and the RTI process mirror the federal guidelines and are found in the WACS numbered 392-172A-03050 through 172A-03060. Section 392-172A-03074 outlines the requirements for documenting the observation of students suspected of having a specific learning disability and section 392-172A-03080 describes the requirements for the specific documentation of the eligibility determination. Both incorporate the federal requirements. Several of these sections elicited questions during the public comment period and the OSPI responses—including some revisions to the draft regulations—are available on the website. If you are interested in reading these WAC sections and/or the official responses to the public comments, please see the online versions at http://www.k12.wa.us/SpecialEd/default.aspx Two other sections describe the state guidelines on using the severe discrepancy model. The first addresses the use of discrepancy tables for determining severe discrepancy. If a school district chooses to use this method of identifying students, the WACs state that: [The district] will use the OSPI’s published discrepancy tables for the purpose of determining a severe discrepancy between intellectual ability and academic achievement. The regulations go on to state that these tables are “developed on the basis of a regressed standard score discrepancy method that includes”: a) The reliability coefficient of the intellectual ability test; b) The reliability coefficient of the academic achievement test; and c) An appropriate correlation between the intellectual ability and the academic achievement tests. Finally, for purposes of determining SLD eligibility, this WAC section states that, “the regressed standard score discrepancy method is applied at a criterion level of 1.55.”15 The second new section that should be highlighted concerns the method for documenting severe discrepancy. The regulation states that in applying the severe discrepancy tables, the following scores will be used: a) A total or full scale intellectual ability score; b) An academic achievement test score which can be converted into a standard score with a mean of one hundred and a standard deviation of fifteen; and c) A severe discrepancy between the student’s intellectual ability and academic achievement in one or more of the areas [oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skill, reading fluency skills, reading comprehension, mathematics calculation, mathematics problem solving] shall be determined by Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Page 8 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 applying the regressed standard score discrepancy method to the obtained intellectual ability and achievement test scores using the tables referenced above.16 This all sounds very objective and numbers driven. However, our WACs also allow educators to apply professional judgment to determine the presence of a specific learning disability. Specifically, the regulation allows the evaluation group to use data obtained from formal assessments, reviewing of existing data, formal assessments of student progress, observation of the student, and information gathered from all other evaluation requirements . . . to determine if a severe discrepancy exists. When applying professional judgment, the group shall document in a written narrative an explanation as to why the student has a severe discrepancy, including a description of all data used to make the determination through the use of professional judgment.17 In addition to these potentially significant changes in the identification or students with SLD, the IDEA 2004 was also amended to reflect a Congressional emphasis on delivering quality instruction based on scientifically-based research, and ensuring that students who are struggling in school receive services as soon as possible. Two of the major changes were introducing the idea of Response to Intervention and Early Intervening Services. Although students with a variety of disabilities and/or academic problems may receive services under these programs, many will be those who do not qualify for the new eligibility requirements of SLD and/or are at risk for becoming eligible. Both issues are addressed below. B. Response to Intervention (RTI) Response to Intervention is a new approach introduced in IDEA 2004 to determine whether a struggling child actually has a disability as defined by IDEA or simply needs more intensive regular education support to be successful in the classroom. In fact, IDEA 2004 does not use the phrase “Response to Intervention” but rather the phrase “response to scientific researchbased intervention.” However this federal terminology is commonly referred to as “Response to Intervention” or either RTI or RtI. This Bulletin uses RTI. RTI has been defined by the National Center on Research in Learning Disabilities (NCRLD) as “[a]n assessment and intervention process for systematically monitoring student progress and making decisions about the need for instructional modifications or increasingly intensified services using progress monitoring data.”18 Although students with a variety of difficulties could benefit from the RTI process, it is aimed at identifying students with learning disabilities earlier than generally possible with traditional discrepancy models. An underlying assumption of RTI is that most students should benefit from a quality, regular education curriculum and therefore educational difficulties may be based on inadequacies in instruction/curriculum.19 Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 Page 9 of 15 OSPI has described RTI as an “integrated approach to service delivery that encompasses general, remedial and special education through a multi-tiered services delivery model.”20 It usually consists of three levels of intervention and individualization, though it can vary. If a child does not respond to the first level of intervention, the child will typically be moved to the next level of RTI instruction and so on through the various tiers until the appropriate interventions are identified. Core Characteristics of RTI, as identified by the NCRLD are: 1. Students receive high quality instruction in their general education setting. 2. General education instruction is research-based. 3. General education instructors and staff assume an active role in students’ assessment in that curriculum. 4. School staff conducts universal screening of academics and behavior. 5. Continuous progress monitoring of student performance occurs. 6. Continuous progress monitoring pinpoints students’ specific difficulties. 7. School staff implements specific, research-based interventions to address the student’s difficulties. 8. School staff uses progress-monitoring data to determine interventions’ effectiveness and to make any modifications as needed. 9. Systematic assessment is completed of the fidelity or integrity with which instruction and interventions are implemented. 10. The RTI model is well described in written documents (so that the procedures and criteria used in schools can be compared to the documents). 11. Sites can be designated as using a “standardized” treatment protocol or an individualized, problem-solving model. 12. A child may be separately assessed for a disability at any time throughout the RTI process. This last point is important to highlight. RTI may not be used as a means of delaying or refusing to conduct a special education evaluation if the LEA suspects that the child has a disability or if the parents request that the school evaluate the child.21 1. RTI in federal and state law Under IDEA 2004, if a school suspects that a student has a SLD, the school must be allowed by state law to use a process based on the child’s response to specific, research-based intervention to determine eligibility, and may permit the use of other alternative researchbased procedures. Not responding or making sufficient progress within that intervention is an indication that learning disabilities may lie at the root of the child’s academic difficulties.22 States can choose the manner in which they implement a RTI process as one part of a comprehensive evaluation.23 However, RTI cannot be the only tool used to determine if a child is eligible for special education and does not replace the need for a comprehensive evaluation.24 Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Page 10 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 WAC 392-172A-03060 spells out the process by which SLD students may be identified through RTI in our state. Washington State school districts that use RTI must adopt procedures that include the following elements: Universal screening and/or benchmarking at fixed intervals at least three times throughout the school year; Provide a high-quality core curriculum designed to meet the instructional needs of all students; Use scientific research-based interventions for students identified as needing additional instruction; Use scientific research-based interventions that are appropriate for the student’s identified need, implemented with fidelity; Use a multi-tiered model, developed to deliver both the core curriculum and strategic and intensive scientific research-based interventions in the general education setting; Frequently monitor individual student progress in accordance with the constructs of the multi-tiered delivery system and consistent with the intervention and tier at which it is being applied; and Decision making using problem solving or standard treatment protocol techniques based on, but not limited to, student centered data that includes curriculum based measures, available standardized assessment data, intensive interventions, and instructional performance level. These procedures must be used to establish that: The student’s general education core curriculum instruction provided the student the opportunity to increase her or his rate of learning; Two or more intensive scientific research-based interventions were implemented with fidelity and for a sufficient duration, in addition to or in place of a general education, and did not increase or allow the student to reach the targets identified for the student; and The duration of the intensive scientific research-based instruction was long enough to gather sufficient data points below the student’s aim line to demonstrate student response for each of the interventions through progress monitoring to determine the effectiveness of the interventions. 2. Practice Considerations Washington State is encouraging schools to wait until they have scaled up their RTI efforts before using it for SLD determinations. OSPI has made it clear that there is no “cookie cutter” model for implementation of RTI but that flexibility is required. Due to the state’s cultural and linguistic diversity in student populations, resources, geographic areas, and rural, urban and suburban populations, it is expected that no two school districts or even school buildings will implement RTI in precisely the same way. Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 Page 11 of 15 In order to assist schools in designing and implementing effective RTI programs effort, OSPI has developed a comprehensive manual titled Using Response to Intervention (RTI) for Washington’s Students. It explains the principles and components of the RTI process, guidelines related to decision making within a RTI system, recommends how to use RTI data in identifying SLDs, answers common questions, and identifies additional resources to use in developing district RTI systems.25 It is available online at http://www.k12.wa.us/SpecialEd/pubdocs/RTI/RTI.pdf There is an increasing amount of other information available to school professionals on how to implement a RTI process, including how RTI works in conjunction with special education services at and with students who are members of cultural, racial or linguistic minorities. Some of these RTI resources are available at http://www.k12.wa.us/SpecialEd/RTI.aspx. Although there are few reported “problems” with implementation of RTI as of yet, possible issues have been raised in the literature. Whether these concerns will present barriers to implementation are not going to be clearly understood for a few years, but they may be useful food for thought as educators begin the process of introducing RTI in their buildings. In summary the following issues have been the focus on academic commentary. 1. Broad policy concerns including the fact that (a) effective implementation places a heavy load on public school teachers who do not have the training or incentives to achieve its optimistic goals; (b) RTI alters the definition of learning disabilities by changing the way in which students are identified, ultimately shifting the category of children protected by IDEA by using a universal standard based on average performance; and (c) RTI focuses on low achievement rather than processing difficulties, failing to get at the root source of the problem.26 2. General implementation questions including, (a) what if a student’s teachers are not highly qualified [as required under IDEA and NCLB]? (b) What if the children’s parents do not receive documentation of achievement at regular intervals? (c) In practice, will RTI actually expedite the receipt of student assistance? and (d) How do we judge assessments and do assessments accurately reflect what students need to know?27 3. Concerns related to the amount of time special educators will have to work with noneligible students. Related to this issue is the “problem” of students who are enrolled in private schools as a group that has been highlighted as presenting possible complications for public educators who are required under IDEA 2004 and state law to determine whether they are in need of special education services. Since the leading non-discrepancy based model is now Response to Intervention, and public school districts do not control the bulk of a private student’s instructional day, it is questionable how the public school can obtain meaningful results under designated time constraints.28 In addition to RTI, Congress introduced another “new” idea to IDEA 2004 that has the potential to impact the services provided to students with learning disabilities who may not have the level of difficulty required to qualify for special education services. It is described below. Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Page 12 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 C. Early Intervening Services IDEA 2004 provides states with the option of using some of their Part B funding to implement Early Intervening Services (EIS). Our recently adopted state special education regulations describe the EIS rules if a Washington school district chooses to implement such a program.29 Such services are based on catching problems early in the school experience for primary and secondary students (excluding preschoolers), with an emphasis on the early grade levels (K3rd).30 Under the federal regulations, EIS are activities that support students who are not currently eligible for special education but need additional support to be successful in the general curriculum, and can include activities to support the development of RTI.31 In fact, parental notification is not required for screening by a specialist or teacher to determine appropriate instructional strategies for these children as the screening is not an evaluation for special education services.32 EIS can include professional development for teachers and other school staff to allow them to deliver “scientifically based” academic instruction and behavioral interventions including scientifically based literacy instruction.33 EIS can also include providing educational and behavioral evaluations, services and supports, and where appropriate, instruction on the use of adaptive and instructional software. The law is very clear that EIS do not create any right to free appropriate public educational services under IDEA nor can they be used to delay “appropriate evaluation of a child suspected of having a disability.”34 If a state chooses to introduce EIS, local districts are authorized under the federal special education law to use up to 15% of their Part B funds (funds to implement services to children ages 3-21 years), minus any maintenance of effort reductions, in combination with other funds, to create and implement an EIS program.35 Appendix D to the IDEA contains two examples of how EIS would impact the Part B funds available to the district. First, if 15% of the funding available for early intervening services is greater than the local maintenance of effort reduction (50% of the increase in the LEA grant over the prior year's grant) or if the 15% of the available funding is less than the local maintenance of effort reduction. This limitation means that some LEAs will not be able to engage in early intervening service delivery, based only on the amount of their Part B grant in the current and prior year. The calculations involved are straightforward but clearly a state decision either way will impact the funds available for Part B services. In reality, a state will need to make decisions about how much funding can be made available for EIS without jeopardizing services for special education students. The financial considerations involved in using Part B monies for early intervening when LEAs are already struggling to provide services to students with IEPs may also discourage school districts in implementing early intervening services. Early Intervening Services are essentially another tool provided to schools by IDEA 2004 to take early and deliberate action to assist struggling students. The rationale is Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 Page 13 of 15 commonsensical—the earlier students’ learning problems are identified, the earlier students can be helped, reducing the likelihood that they will require more remediation. Not only are such services beneficial to students to maximize their opportunities to succeed, but implementation of EIS would also theoretically be less expensive—at least in the long-term— for state educational agencies. However, we won’t know whether that is true or not for a few years. In order to collect that data, if funds are used for an EIS program, the districts must report to OSPI the number of students served and those that become eligible for special education within two years.36 As mentioned in the earlier discussion of RTI, EIS can be considered one aspect of the RTI process. How these two “new” interventions may impact the outcomes for students who have historically been identified and served under IDEA is unknown at this time. Some schools implemented aspects of RTI and EIS in their buildings before the IDEA 2004 amendments but for many schools these interventions are new. It will take several years of implementation of the IDEA amendments that address identification and delivery of services to students struggling academically before educators and policy makers will have the data they need to evaluate whether the Congressional goal of improved academic performance for students is positively affected by changes in the law. III. Online Resources on Learning Disabilities, RTI and EIS Federal Department of Education: US Federal Dept of Education (IDEA 2004 website): http://idea.ed.gov/ Series of Documents issued by OSEP to assist school districts in implementing IDEA 2004. Eligibility for SLD at http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/%2Croot%2Cdynamic%2CTopicalBrief%2C23%2C State Education Department (OSPI): Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, Special Education (2006). Using Response to Intervention (RTI) for Washington’s Students Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction http://www.k12.wa.us/specialed/IDEA_2004.aspx Additional Resources on RTI: http://www.k12.wa.us/SpecialEd/RTI.aspx resources for RTI National Education Resources: FAQs on SLD from the National Center for Learning Disabilities. http://www.ncld.org/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=283 Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Page 14 of 15 Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 For those interested in a very comprehensive resource on the changes in the special education law related to specific learning disabilities, including determining eligibility, NICHY has made their training materials available on-line http://www.nichcy.org/training/contents.asp#eval3 1 It is important to remember that many disabled students who are not found eligible for IDEA services, may be eligible for educational services under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (Section 504), the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) as well as the Washington State Law Against Discrimination (RCW 49.60). The definition of who is covered—i.e., who is disabled—under these laws differs. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with a disability under any program that receives federal assistance. Public school districts, institutions of higher education, and other state and local education agencies receive these funds and therefore must follow Section 504. Specifically, schools must identify, evaluate and develop plans to ensure that students have the same access to educational opportunities as nondisabled students. ADA extends the nondiscrimination protections of Section 504 to private employers, state and local governments, and any privately owned business or facility open to the public. It prohibits discrimination against an individual by reason of their disability. All IDEA eligible students are protected by Section 504 and the ADA. RCW 49.60 is a civil rights statute that prohibits discrimination based on the presence of any sensory, mental, or physical disability in public areas. 2 See an interesting chapter “Rethinking Learning Disabilities” at http://www.edexcellence.net/library/special_ed/special_ed_ch12.pdf 3 34 CFR §300.8(c)(10)(i)(ii). 4 WAC 392-172A-01035 k(i), (ii). 5 20 USC §1414(b)(6)(A). 6 20 USC §1414(b)(6)(B). 7 34 CFR §300.307. 8 34 CFR §300.308. 9 34 CFR §300.309(a)(1)(2). 10 34 CFR §300.309. 11 34 CFR 300.310. 12 34 CFR §300.311. 13 WAC 392-172-128 14 WAC 392-172A-03045 15 WAC 392-172A-03065 16 WAC 392-172A-03070 17 WAC 392-172A-03070(2). 18 National Center on Research in Learning Disabilities (NCRLD) (2006). Retrieved on June 31 from http://www.ncld.org/ 19 Hozella, P. (n.d.). Training Module 6: Early Intervening Services and Response toIntervention, Slides and Discussion. Office of Special Education Programs, U.S.Department of Education at 9. Retrieved on May 15, 2007 from www.nichcy.org/training/6-discussion.doc Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington. Special Ed Law Quarterly, Bulletin #10 20 Page 15 of 15 . Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, Special Education (2006). Using Response to Intervention (RTI) for Washington’s Students at 2. 21 Id at 10. 22 Id at 12. 23 Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services Policy Letter (March 2007). 24 IDEA §1414(b)(2)(B), 25 Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, Special Education (2006). Using Response to Intervention (RTI) for Washington’s Students at 1. 26 Townsend, N. Framing a Ceiling as a Floor: The Changing Definition of Learning Disabilities and the Conflicting Trends in Legislation Affecting Learning Disabled Students. 40 CREIGHTON L. REV. 229 (2007). 27 Blackwood, E.M. Special Education: Will the “Improvements” Decrease Protections for Parents and Students? 32 SUM VT. B.J. 52 (2006 28 Weber, M. Services for Private School Students under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act: Issues of Statutory Entitlement, Religious Liberty, and Procedural Regularity, 36 J.L. & EDUC. 163 (2007). 29 WAC 392-172A-06085. 30 71 Fed. Reg. at 46627. 31 34 CRF §300.226 32 34 CFR § 300.302 33 34 CFR §300.226(b) 34 34 CFR §300.226(c) 35 34 CFR §300.2269(a). 36 WAC 392-172A-06085(4)(a)(b). Copyright © 2007 by University of Washington.