Bibliografia Provisória - Office of the High Commissioner on Human

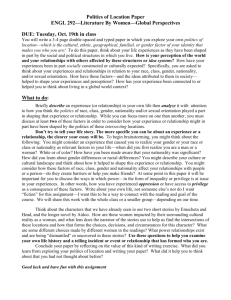

advertisement