Protocol for hatching and raising Western Snowy Plovers

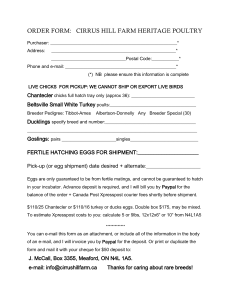

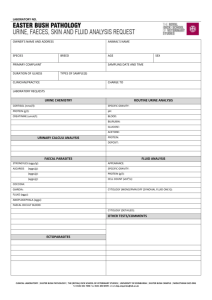

advertisement

PROTOCOL FOR HATCHING AND RAISING WESTERN SNOWY PLOVERS IN CAPTIVITY. August 4, 2008 Introduction At Coal Oil Point Reserve, we hatch abandoned plover eggs and raise the chicks in captivity until fledgling age. Our goal is to learn about techniques of rearing WSP in captivity, using eggs that would be otherwise lost. It is important to realize that captive rearing of plover eggs is very time consuming, stressful, and expensive. It should never be an alternative to proper beach management to produce a sustainable natural breeding population. I- Collecting and transporting eggs from the field Plover eggs are very fragile. The shells are thin and the embryos can die if handled roughly. The best way to transport the eggs without them shaking, is to have a container with sand and bury the eggs half way into the sand, large side up. Hold the container on your hand while walking away from the beach. Transport the eggs as soon as you can. Plover eggs with embryos are known to be able to be buried under the sand for 11 days and still hatch. However, the longer the changes in temperature, the more likely is for the embryo to die to develop weak. Typically, the embryos are most susceptible to changes in temperature in the first and last few days. If possible, maintain the temperature warm (i.e. turn heater on in the car). Be careful to not overheat the eggs. A temperature higher than 99.5F is more dangerous than a temperature that is too low. II- In the nursery The nursery is a protected and insulated building where the eggs and very young chicks stay. Our nursery is a 10 x 10 sturdi-built shed, insulated in the interior with 1 inch Styrofoam (Fig 1). The nursery contains an area for the incubators, another one with terrariums to keep the small chicks, shelves for supplies, and another table for testing eggs and handling chicks. Type of incubator Use a plastic incubator that can be washed and sterilized such as Brinsea. Styrofoam incubators cannot be sterilized. Use quail-size egg trays to organize the plover eggs Incubator setting The protocol for incubating WSP eggs is the same as for incubating most of other birds. The incubator should be set at 99.5 F and 40-50% humidity. Even if the incubators say that they come from the factory calibrated, they don't. Make sure you buy another thermometer to test the temperature. I could never get the humidity to come even close between the test thermometer and the incubator. Eggs should be rotated at least 4 times daily or be rotated automatically with a automatic egg turner. Stop the eggs from rotating 3 days before hatching so the chicks can find a good hatching position (see hatching below) Routine maintenance Discard bad eggs as soon as you know they are dead or infertile. Alive eggs move in the water when floated. If in doubt, get a second incubator for these eggs, to avoid the risk of contaminating eggs that are good (see hatching problems below). Clean incubator when dirty and desinfect it after each season or each batch of eggs. Test eggs with candler or floating in clean water every few days. Eggs that are more than 2 weeks and don't move in the water should be separated. Eggs that have not developed an embryo after a week, should be separated. There are several guides in the internet that describe what you should see when candling eggs. Maintain a log with date, time, and condition of eggs and incubator settings. Hatching problems Luckily, hatching plover eggs is very much like any hatching any other bird and a number of resources for troubleshooting hatching problems are available on the web. We had a hatching problem in 2008 and now are nearly certain that the problem was that there was a dead egg mixed with live eggs in the same incubator. The egg eventually exploded in the incubator. The bacteria in the dead egg infected the good ones. The symptoms we observed were chicks starting to pip a hole in the egg a week earlier and then fail to hatch. The solution to this problem was to separate the eggs that were suspected to be dead to another incubator, or discard them if we knew for sure that they were dead. The most reliable way to test eggs after 10 days of incubation is to float the egg on a clean warm water. If the egg is alive, the egg will move (make sure it is not you moving the table). Eggs that are not yet floating do not move because the embryo is still too small. Infertile eggs will eventually float but they do not move. If an egg should move, but it doesn’t, I test it again later. You should record all activities in the incubator, with fates and times of testing eggs and the fate of each egg. Failed eggs should be cracked open to determine if they were infettile (yolk and egg white intact), with a dead young embryo or a dead near-term embryo. Hatching 3 days before hatching, place the egg in a small container with clean sand in the incubator. This way the egg will not rotate but you don't need to turn of the automatic turner for the other eggs. When the chick is hatched, remove the egg shells and leave the chick in the incubator for approximately 6 hours, or until the chick can move around (Figure 2). Figure 2. Chick a few hours old, when it is ready to be moved from the incubator to the terrarium. Watch a movie of a new chick in the incubator (but note that we don't dry the chick anymore, instead we provide a feather duster with no loose strings): http://www.calliebowdish.com/SnowyPloverNewborns2005.ht m Indoor brooder A brooder is a place with a source of warmth that the chick can spend its first 5 days until it is capturing prey well. We use an aquarium, with beach sand on the bottom, and a warm lamp. If possible, use 2 lamps in case 1 fails. The chick should be able to choose warm and cool areas in the terrarium. An incandescent bulb is a good source of warmth and you can see if it fails. Ceramic lamps can get too hot and you have to touch to see if they are working. The chick likes to brood under a feather duster. Make sure there are no loose strings where they could get entangled. A very small dish of water is good. Too large of a dish and they can fall in and drawn. Keep water at all times and change the water daily. Backup system We learned during a power outage that a nursery needs to have a backup for power. We purchased a Honda EU2000 generator to provide power in an emergency for the warm lamps and the incubator. You also need a backup incubator. If one fails, you need another one to transfer the eggs immediately. III- Outdoor aviary The aviary is a large flight cage where the chick will grow until it is time for their release. After 4-5 days, the chicks are moved the outdoor aviary (Figure 3). The aviary should be a larger version of the brooder, with a warm lamp, water, and a shaded area. The aviary is made of fine wire mesh and it has plexiglass all around the bottom. That way, predators cannot reach the chicks, live food stays in the aviary, and the chicks don't hurt their beaks in the wires. A shallow plate of water can used for the chicks to bathe. We cover the aviary cement floor with sand and add kelp to make the substrate look as much as possible to a natural beach. The height of the warm lamp will depend on the intensity of the light bulb. Use your hand on the sand to determine the position where your hand is warm but not too hot. Feeding of chicks We use beach hoppers as the main food source for captive plovers. Mealworms are used occasionally for variety. Chicks start eating the next day they hatch. At this age they will eat very small live hoppers, about 2 mm in length. As they grow and become more agile, the size of the hoppers they eat increase (Figure 4). We feed chicks every 2 hours, at daylight hours. We give the chicks handfuls of hoppers, until they stop eating. . A 3-week old chick eats about 5-8 large (or many more small) hoppers per feeding. Feeding plover chicks with beach hoppers is very time consuming. We will be experimenting with automatic feeders, to reduce the number of times we need to be present. We will experiment with other foods that can be placed in a bowl. We will continue feeding live hoppers so the chicks can develop the skills for catching live food. Figure 4. Sizes of beach hoppers offered to plover chicks. In the first few days, chicks will eat very small hoppers as shown in the left. As they grow they are capable of eating larger hoppers, even adult ones (right). Collecting beach hoppers We collect beach hoppers under the kelp wrack, on the beach, everyday. The best time to collect hoppers is in the morning and at low tide. Lift the kelp and, if you see many hoppers jumping under it, quickly shake the kelp in a bucket. Do this several times until you have sufficient hoppers for a day or 2. The hoppers are kept on a bucket with wet sand and kelp. Our beach is very reach in kelp wrack and beach hoppers. It may not be feasible to use beach hoppers as the sole food source in other areas where hoppers are scarce. Releasing the chicks The chicks are ready for release when they can fly, their tails will be fully gown. This is about 35 days. If possible, release chicks together. We like to use a birdcage to transport them to the release site (Figure 6). Then leave the cage on the sand, where they will be can see the beach for about 10 minutes, for the chicks to get used to their surrounding. Then open the door of the cage. The release site should be an area that other plovers use. However, avoid releasing chicks to close to other nesting plovers. They will be aggressive towards the released juveniles. Figure 6. Nicolle Cerra opening the cage to release 3 plover chicks raised in our nursery in 2008. For questions, please contact Cris Sandoval at Sandoval@lifesci.ucsb.edu