Understanding Behavior

advertisement

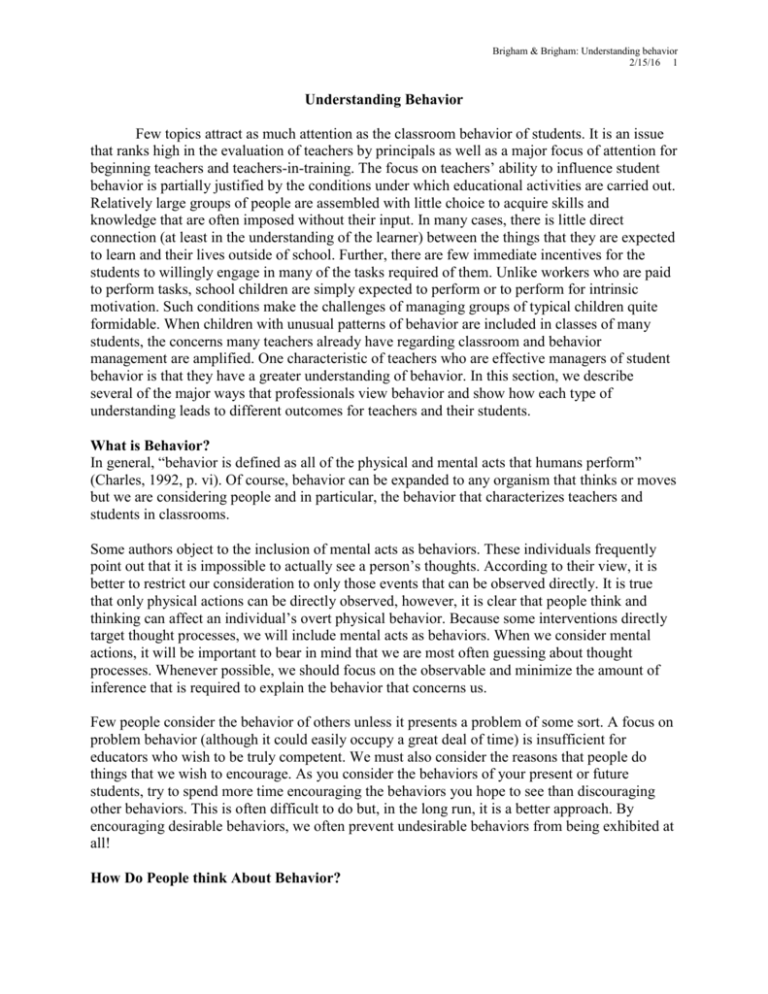

Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 1 Understanding Behavior Few topics attract as much attention as the classroom behavior of students. It is an issue that ranks high in the evaluation of teachers by principals as well as a major focus of attention for beginning teachers and teachers-in-training. The focus on teachers’ ability to influence student behavior is partially justified by the conditions under which educational activities are carried out. Relatively large groups of people are assembled with little choice to acquire skills and knowledge that are often imposed without their input. In many cases, there is little direct connection (at least in the understanding of the learner) between the things that they are expected to learn and their lives outside of school. Further, there are few immediate incentives for the students to willingly engage in many of the tasks required of them. Unlike workers who are paid to perform tasks, school children are simply expected to perform or to perform for intrinsic motivation. Such conditions make the challenges of managing groups of typical children quite formidable. When children with unusual patterns of behavior are included in classes of many students, the concerns many teachers already have regarding classroom and behavior management are amplified. One characteristic of teachers who are effective managers of student behavior is that they have a greater understanding of behavior. In this section, we describe several of the major ways that professionals view behavior and show how each type of understanding leads to different outcomes for teachers and their students. What is Behavior? In general, “behavior is defined as all of the physical and mental acts that humans perform” (Charles, 1992, p. vi). Of course, behavior can be expanded to any organism that thinks or moves but we are considering people and in particular, the behavior that characterizes teachers and students in classrooms. Some authors object to the inclusion of mental acts as behaviors. These individuals frequently point out that it is impossible to actually see a person’s thoughts. According to their view, it is better to restrict our consideration to only those events that can be observed directly. It is true that only physical actions can be directly observed, however, it is clear that people think and thinking can affect an individual’s overt physical behavior. Because some interventions directly target thought processes, we will include mental acts as behaviors. When we consider mental actions, it will be important to bear in mind that we are most often guessing about thought processes. Whenever possible, we should focus on the observable and minimize the amount of inference that is required to explain the behavior that concerns us. Few people consider the behavior of others unless it presents a problem of some sort. A focus on problem behavior (although it could easily occupy a great deal of time) is insufficient for educators who wish to be truly competent. We must also consider the reasons that people do things that we wish to encourage. As you consider the behaviors of your present or future students, try to spend more time encouraging the behaviors you hope to see than discouraging other behaviors. This is often difficult to do but, in the long run, it is a better approach. By encouraging desirable behaviors, we often prevent undesirable behaviors from being exhibited at all! How Do People think About Behavior? Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 2 There are several schools of thought that explain different parts of the human behavior puzzle or that explain the same part in different ways. We will briefly consider four of the major approaches to understanding behavior. These approaches are classified as (a) behavioral, (b) biophysical, (c) ecological, and (d) psychodynamic models1. When considering the models, teachers should ask themselves the following questions: 1. Does the model describe the behavior that I am seeing or the behavior that concerns me? 2. Does the model explain a full range of behaviors or just a small slice of the behavior that concerns me? 3. How much inference (guessing about what is going on) does the model require? 4. Does the model fit within my areas of expertise and influence or does it require specializations beyond those possessed by educators? 5. Does the model yield verifiable statements? That is, can we test it in some way to show that the statements made actually account for the behavior observed? 6. Does the model provide predictive utility? That is, does the model allow relatively accurate predictions about what people in a given situation are likely to do? 7. Does the model have parsimony? Is it the simplest model that accounts for the observed behavior? Alberto and Troutman (1999) pointed out that, while the simplest explanation is not always correct, striving for parsimony prevents us from losing touch with reality in favor of imagination. In the real world, people are rarely adherents to one and only one school of thought regarding behavior. Rather, they use different explanations to explain different behaviors. This is called an eclectic approach. There are advantages to being eclectic but it is also important to have a base of operations so that one can avoid drifting from explanation to explanation on the basis of convenience, whim, or emotional reactions. Finding and associating with one primary explanation also allows people to have a more organized and systematic understanding of behavior. Without a theoretical anchor of some sort, one is probably just collecting a “hodgepodge” of ideas. The Behavioral Explanation The behavioral explanation suggests that all behavior is learned and that behaviors are learned as functions of events within the environment. When maladaptive behaviors are observed, they should be considered to be the outcomes of inappropriate learning. Similarly, adaptive behaviors are the result of learning appropriate responses to various prompts in the environment. Behavioral practitioners support or change behavior by arranging antecedent events and consequences. A great deal of effort goes into making precise definitions of the behavior in question and collecting objective reliable data regarding frequency, duration, setting, antecedent events, and the consequences surrounding the behavior. 1 A number of other explanatory models of human behavior exist. Our intention here is to provide the reader with an understanding of how behavior is understood from different perspectives and not to provide an exhaustive treatment of the topic. Also, our treatment of these perspectives is admittedly quite superficial. For additional explanations of the different models of human behavior and classroom management, see: (Alberto & Troutman, 1999; Charles, 1992; Kaiser & Rasminsky, 2003; Kauffman, 1997; Kerr & Nelson, 2002; Rosenberg, O'Shea, & O'Shea, 2002; Walker, Colvin, & Ramsey, 1995; Wehman, 2001). Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 3 Another aspect of the behavioral approach is the definition of consequences by their impact on the behavior. In general, there are three classes of consequence for any behavior: reward, punishment, or extinction. Consequences that strengthen behaviors (increase in frequency, duration, or probability) are considered to be rewards or reinforcers. Consequences that weaken behaviors (decrease in frequency, duration, or probability) are considered to be punishments. In general terms, these principles mean that people do what they do mostly to (a) get something they want or (b) to avoid or escape something that they find unpleasant. Many teachers make the mistake of assuming that their students want the same things that they do or that each student wants the same things as most of his or her peers. Public acclaim for achievement is considered a reward by most schools. However, a young woman we worked with in Indiana would only complete her assignments if we agreed not to compliment her in public. The public acclaim was serving as a punishment for this student. Similarly, after-school detentions are considered to be punishments for most students. When we tried these with one young man in Iowa, we found that his rate of misbehavior skyrocketed. We realized that we were rewarding his misbehavior in some way. Therefore, we reversed the consequence. In order to stay after school this student was required to complete assignments and exhibit positive behavior in the classroom. His behavior improved and he was rewarded by spending an afternoon a week after school helping his teacher clean up the classroom. These examples may be a bit unusual, but they illustrate the principle that reward and punishment are defined by their impact on the person experiencing them. When a behavior fails to elicit an active response from the environment, it is usually weakened. A weakening of behavior due to lack of contingent response is called extinction. The advice to ignore problem behavior so it will go away is based on extinction. If a student is executing a behavior to gain a teacher’s attention, he or she may stop the behavior if the teacher ignores it. However, it is probable that the student is executing the behavior because it has resulted in a desirable outcome in the past. If teacher attention is the reinforcing event, the student will be likely to increase or intensify the behavior before he or she gives up. The name for this phenomenon is “extinction burst.” Few educators are warned that ignoring the behavior sometimes makes it worse. Of course, if the student is executing the behavior for a different reason (e.g., attention from classmates), being ignored by the teacher will be of no consequence whatsoever. There is another form of reinforcement that teachers and students often use upon each other. It is a way of increasing behavior in frequency, duration, or probability and is thus a form of reinforcement. However, this form of reinforcement encourages behaviors to take place by removing or decreasing a pre-existing unpleasant condition or stimulus. We have all experienced this without really paying attention to it. When we eat, the feeling of hunger (and for some people, other feelings like boredom, anxiety, or tension) abates. Increasing a target behavior by removing a noxious condition contingent fromthe target person is called “negative reinforcement.” In other words, negative reinforcement increases behavior that results in either escaping or avoiding an aversive (unpleasant) situation. Negative reinforcement is not a recommended way of dealing with students in classrooms; however, students frequently use negative reinforcement to encourage teachers to cancel Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 4 assignments or tests or to alter classroom expectations. In doing so, they may present the teacher with unpleasant behaviors such as whining, or complaining until the teacher complies with the students’ desire (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997). It appears that giving in to negative reinforcement behaviors only stops the behavior for a short time. In the long run, operating with negative reinforcement only elicits more of this unpleasant manner of interaction. The behavioral approach is sometimes criticized as cold, mechanistic, and overly focused on extrinsic rewards and punishments. However, most of us are pleased to be paid for our efforts and strive to avoid sanctions and ridicule in our work. Others criticize behavioral approaches as manipulative because the teacher seeks to control the settings that prompt behavior and the consequences follow behavior. However, much of effective teaching involves setting up situations where students can obtain certain educational objectives and acknowledging their efforts when they do. Behavioral practitioners view classroom behavior as simply another skill that the student can learn. Given that, why would a teacher not establish environments where their students can be successful and ensure that successful efforts resulted in pleasant outcomes for their students? The Ecological Explanation The ecological model focuses on the individual as a member of several social systems. For children, these systems often include classroom, peer group, and family. Many people have more than these three systems but most school-aged children have at least these three systems in common. Rather than focusing exclusively or primarily on the behavior of the target student, ecological practitioners assess environment-behavior interactions as well as the ecological contexts in which student behaviors occur (Greenwood, Carta, Kamps, & Arreaga-Mayer, 1990). Proponents of this theory suggest that an individual’s performance is at least partially determined by the nature and type of interactions the student has with the environment and people in the environment. The task in an ecological approach is to identify classroom, family, peer group and community environmental factors that facilitate or reduce the occurrence of specific behaviors and provide information that may be used to change instruction (Greenwood, Carta, Kamps, Terry, & Delquadri, 1994). Ecological practitioners (sometimes called ecobehaviorists) often use many of the same tools as the behavioral practitioners which were described in the previous sections; however, they tend to look for and increase the naturally occurring contingencies that support positive behavior while minimizing those contingencies in the environment that support undesirable behavior (Scott, Liaupsin, & Nelson, 1999). One recent example of this approach appeared in a study by Wallace, Reschly Anderson, Bartholomay, and Hupp (2002). They examined teacher behaviors, student responses, and classroom ecology in 118 inclusive classrooms in four high schools with demonstrated success at achieving good outcomes for students with and without disabilities. Their analysis led them to conclude that “active student engagement in academic learning, little time spent exhibiting competing responses, being the focus of teacher attention, and having teachers spend more than three quarters of their time focusing on and preparing students for learning and teaching them appear to be the important factors associated with the successful inclusive high school classrooms included in this study” (p. 356). Other ecobehavioral Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 5 practitioners enlist the peers or family members to support positive behavior on the part of their target students. The ecological approach has the benefit of being less intrusive because it employs naturally occurring supports already existing in the environment. Because these supports already exist, they are likely to be maintained after any formal intervention is concluded. However, it is sometimes difficult to identify naturally occurring supports with sufficient intensity to attain the educator’s goals. Biophysical Explanations Biophysical explanations suggest that behavior is the result of genetic or biochemical processes in the body. Medical intervention is often involved with behaviors that are explained in this manner. Educators need to be aware of biophsycial explanations because they will see a number of children whose behavior is related to a genetic or chemical condition. For example, schizophrenia, selective mutism, depression, and hyperactivity can all be related to the individual’s biology. Some forms of behavior problems respond better to medical treatment than to other forms of interventions (Brigham & Cole, 1998; Forness & Kavale, 2001). Nevertheless, educators are not trained in medical diagnosis and management procedures; therefore, they should hesitate before suggesting a biophysical explanation for a given behavior for one of their students. Also, many medical conditions are often, in part, identified by their non-responsiveness to other forms of treatment (e.g., behavior management or ecobehavioral support). Rather than focusing on biological explanations teachers should first ensure that the behavior and ecological aspects of their classrooms are as supportive of their students as possible. By documenting effective behavioral and ecological supports teachers can (a) assist in identification of biologically based behavior problems by helping to rule out alterable environmental causes and (b) establish effective instructional environments for their students who have benefited from behavioral medical treatment. Psychodynamic Explanations There are many forms of psychodynamic or psychoanalytic theories. Most of them suggest that undesirable behavior is the result of some hypothesized form of inner turmoil or tension among the dynamic parts of one’s personality. Acceptable behavior according to psychodynamic practitioners will be impossible until these tensions are resolved through psychotherapy. The implication for educators working in a psychodynamic model is to supply a permissive and accepting classroom environment so that the student can work through his or her emotional conflicts. Counseling and other forms of talking interventions are most often associated with this model of understanding behavior. Psychodynamic theorists suggest that gaining insight into unconscious motivations will enable students to exhibit the behaviors necessary for productive engagement in school. Psychodynamic explanations have the advantage of being aligned with many popular conceptions of human behavior. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of psychodynamic interventions has been called into question. An additional problem faced by practitioners of psychodynamic approaches is the limited predictive ability, verifiability and parsimony these theories possess. Further, few teachers can afford to provide a permissive environment for a single student or a group of students while the therapy takes its course. Most teachers find psychodynamic Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 6 approaches to explaining and dealing with behavior unproductive. Nevertheless educators should not discount the power of talking to their students and involving counselors to help students make decisions about their behavior. When To Act When educators understand the behavior of their students, they are in a better position to act to prevent misbehavior, encourage positive behavior and redirect unacceptable behavior. One idea that cuts across all theories of behavior is the notion that it is better to encourage desirable behavior than to suppress undesirable behavior. Teachers who have fewer classroom management problems are those who have the knack of responding positively to their students. It is important to remember that even expert managers of behavior are confronted with misbehavior. When misbehavior is observed, educators must decide whether or not to intervene. Some behaviors that students exhibit are merely annoying to the adults around them and present no real threat to the students, their peers and teachers or the educational process. Other behaviors are clearly detrimental to the students or those around them. Gabel (2000) suggested several guidelines for determining the need to intervene with student misbehavior. In general terms, behavioral interventions by educators are justified when: The behavior differs significantly from peers’ The behavior lessens the possibility of successful learning The behavior is not a cultural difference The behavior represents a serious, persistent, chronic safety threat The behavior is likely to result in disciplinary action When more than one of these features is present, the intervention is not only justified it is necessary, and failure to act may be negligence. There is no need to justify acknowledgment of positive or desirable behavior. Educators should do so as often as they can. In other sections of this website, you will learn about conducting functional behavioral assessments and behavior intervention plans. The procedures you will learn are most compatible with the behavioral and ecological explanations of behavior. It is important to note that even when working in the biophysical and psychodynamic models, educators can use these techniques to support their students and make their classrooms more enjoyable and productive places for themselves and their students. The psychodynamic models are probably the least compatible with the tools presented in the following sections; however, there are times that insight into personal behavior and individual choices can help students and teachers in their tasks. When considering any potential explanation for a given behavior, educators should consider the seven questions presented at the beginning of this paper and accept explanations that answer more of those questions while rejecting those that answer fewer of them. At the present state of development of our knowledge base, most educators find the behavioral explanations to be the most useful. Brigham & Brigham: Understanding behavior 2/15/16 7 References Alberto, P., & Troutman, A. C. (1999). Applied behavior analysis for teachers (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Merrill. Brigham, F. J., & Cole, J. E. (1998). Selective mutism: Developments in definition, etiology, assessment and treatment. In T. E. Scruggs & M. A. Mastropieri (Eds.), Advances in Learning and Behavioral Disabilities (pp. 183-216). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Charles, C. M. (1992). Building classroom discipline (4th ed.). New York: Longman. Forness, S. R., & Kavale, K. A. (2001). Ignoring the odds: Hazards of not adding the new medical model to special education decisions. Behavioral Disorders, 26(4), 269-281. Gable, R. A., & Educational Resources Information Center (U.S.). (2000). Addressing student problem behavior (1st ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Institutes for Research : U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Research and Improvement Educational Resources Information Center. Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., Kamps, D., & Arreaga-Mayer, C. (1990). Ecobehavioral analysis of classroom instruction. In S. R. Schroeder (Ed.), Ecobehavioral analysis and developmental disabilities: The twenty-first century. New York: Springer-Verlag. Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., Kamps, D., Terry, B., & Delquadri, J. C. (1994). Development and validation of standard classroom observation systems for school practitioners: Ecobehavioral Assessment Systems Software (EBASS). Exceptional Children, 61(2), 197-210. Gunter, P. L., & Coutinho, M. J. (1997). Negative reinforcement in classrooms: What we're beginning to learn. Teacher Education & Special Education, 20(3), 249-264. Kaiser, B., & Rasminsky, J. S. (2003). Challenging behavior in young children : understanding, preventing, and responding effectively. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Kauffman, J. M. (1997). Characteristics of emotional and behavioral disorders of children and youth (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Merrill. Kerr, M. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2002). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Merrill. Rosenberg, M. S., O'Shea, L. J., & O'Shea, D. J. (2002). Student teacher to master teacher : a practical guide for educating students with special needs (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Merrill/Prentice Hall. Scott, T. M., Liaupsin, C. J., & Nelson, C. M. (1999). Understanding problem behavior. Retrieved August 15, 2001, from http://serc.gws.uky.edu/pbis/home.html Walker, H. M., Colvin, G., & Ramsey, E. (1995). Antisocial behavior in school: Strategies and best practices. Pacific Grove, Calif.: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co. Wallace, T., Reschly Anderson, A., Bartholomay, T., & Hupp, S. (2002). An ecobehavioral examination of high school classrooms that include students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 68(3), 345-359. Wehman, P. (2001). Life beyond the classroom: transition strategies for young people with disabilities (3rd ed.). Baltimore: P.H. Brookes Pub. Co.