Legal Transcriptions: A Lawyer's Guide to Accuracy

advertisement

Transcriptions for Legal Purposes: A Lawyer’s Guide in Plain English

Wendy L. Bowcher (PhD)

Sun Yat-sen University, China

Fellow, Forensic Linguistics Institute

bowcherw@yahoo.co.jp

“A bad transcription is essentially a false record” (John Olsson

www.thetext.co.uk/forensic_transcriptionfaq.html)

Introduction

Most civil or criminal lawyers have used typed transcripts of spoken language situations such as

interviews, covert recordings, and emergency calls. Many lawyers however, are not fully aware of

the difference that a professional linguist can make to a transcription, and are hence often caught

out with issues concerning transcripts that cost them time and money, and could cost them their

case.

Transcribing naturally occurring spoken language is a specialised skill that many ex-secretaries or

audio experts do not have. Whereas court transcription services generally present very polished

transcripts, transcripts of other types of evidence can vary from good to extremely poor.

Poor transcripts can contain any number and type of errors and assumptions from spelling errors,

inaccurately transcribed language, inappropriate punctuation, incorrectly represented speakers,

“corrected” grammar and no representation of overlapping or interrupting speech.

The next few paragraphs outline some issues with transcripts that need to be considered if a

transcript is to be used for legal purposes.

Features of Spoken Language

Many people believe that spoken language is fragmented and unstructured. This attitude often

comes about when they see spoken language written down. But spoken language is not “meant” to

be written down. While spoken and written language are “different modes for expressing linguistic

meaning”, they are not simply ways of saying the same thing differently (Halliday 1985: 92). They

are generally used in different situations for different purposes. This means that they are structured

differently, so much so that when spoken language, and particularly spontaneous speech is written

down it does indeed appear to be fragmented and unstructured. Halliday (1985: 100) points out

that when we analyse written language we almost always analyse the finished product, but if we

were to treat written language as a dynamic, and to record all the drafting and changing that takes

place, it too, would appear fragmented and unstructured, and indeed, would be difficult to follow.

Spoken language has its own structure which reflects both the dynamic, transient nature of the

situation, and the way in which topics change according to the situation in which the speaking takes

place.

Some of the features of spoken language that make it appear fragmented when written down

include false starts and voiced hesitations.

False Starts

The term “false start” is self explanatory. When we speak, we might start to say something but then

switch midsentence to saying something else. Here are a couple of examples:

Yeah, and it was, it happened just before we decided to leave.

And he said, he told me that we shouldn’t be there.

Many transcriptions do not include false starts because they are not deemed relevant to the purpose

of the transcription. In such cases, the above examples would be represented in the following way:

Yeah, it happened just before we decided to leave.

And he told me that we shouldn’t be there.

Ignoring false starts may make the transcript look neat, and may make reading the transcript easier,

and even when listening to the tape and reading the transcript a listener may disregard the false

starts. But a transcription used in a legal situation needs to represent all false starts, otherwise it is

an incomplete record of what was said. If false starts have not been represented, doubt arises as to

what else may be missing in the transcript.

There may be other advantages to retaining false starts. False starts have a function in spontaneous

speech. They are one of the ways that speakers “negotiate meaning”, in that they allow speakers to

repair what they want to say and to give them time to think ahead (Nyyssonen 1995: 162). When we

consider this function in a legal situation, false starts may point to something useful with regard to

analysing a witness’s recollection of an event. For instance, the difference between “it was” and “it

happened” in the above example is very subtle, with the latter suggesting an event and the former

being more implicit in its reference. In the second example, the switch from “he said’ to “he told

me” could be significant. In the first, the interviewee is not giving any ‘target’ of the saying whereas

in the latter the target “me” is more specific, and this may be significant in the witness’s account of

the incident. It would at least provide an avenue for further investigation of this part of the

witness’s account.

If false starts are ignored, then vital clues as to the intentions or meanings that the witness may have

started to convey would be missed.

Voiced Hesitations

Voiced hesitations (or filled pauses) are another feature of spontaneous spoken language. They are

also another feature of transcripts that are often overlooked by unskilled or unaware transcribers.

Voiced hesitations include the ‘ums’, ‘ahs’ and ‘ers’ that many speakers use during natural

unscripted talk, as in the following examples:

‘I’m on er the corner of Oxford and Darley Streets.’

‘Um no-one from er our group was um there at the time.’

By ignoring voiced hesitations, the transcriber is missing information with regard to the speaker’s

‘planning ahead’ moments. As with ignoring or ‘fixing up’ false starts, the transcript would look

neater, with the above examples appearing as the following:

I’m on the corner of Oxford and Darley Streets.

No-one from our group was there at the time.

In representing the utterances in this way, the reader of the transcript does not get any sense of the

way these utterances were said. Rather, it appears that the speaker has no hesitation or perhaps is

making the statements in a confident and very fluent way. A function of voiced hesitations is to

provide the speaker with time to plan what they wish to say without giving up the floor, another is

that they may be unsure about something (see Clark & Fox Tree 2002 for a discussion of several

functions; see also Swerts 1998). A linguistic analysis showing areas in an interview in which a

speaker used a considerable number of voiced hesitations may raise questions with regard to the

speaker’s recollection or attitudes towards those particular points in the interview. So again,

transcribing voiced hesitations could aid in the setting up of questions and issues for further

investigation.

Transcriber Assumptions

A danger of using an unskilled or unaware transcriber is that they may make assumptions about

what has been said. These may include filling in, correcting, or guessing what has been said.

Sometimes a break in a recording can occur in the middle of a word. In such cases, when the

transcript is for legal purposes, it is inappropriate to ‘fill in’ the missing part because doing so

renders the transcript an incorrect representation of what was there in the recording. It may seem

like a rather trivial point, and in such cases, one can always suggest what the missing part may be,

but filling in what is not there without any note or comment calls into question the integrity of the

transcription and can cause embarrassment for the lawyer who is relying on the transcript to be a

true representation of the recording.

Unclear speech, accented or dialectal variation, and non-native speech patterns can all present

problems for unskilled transcribers.

In many recordings there are speakers who may be difficult to hear, or whose articulation of certain

words and phrases may be quite indistinct, even when the recording has been ‘cleaned up’ by an

audio technician. There are also certain sounds (phonemes) that are sometimes difficult to

distinguish such as /b/ and /v/ or /s/ and /f/. Certain phrases and whole utterances may be difficult

to make out, and there may be many factors that affect speech perception in transcribing a

recording. Fraser (2003) discusses the influence of contextual clues on listener expectations and

perceptions. She argues that

transcription of difficult material must be done by someone who understands

the likely errors in their perception, and can be critical of their own perception,

so as to consider a wider range of options, and judge the level of confidence to

assign to any interpretation. Such knowledge is only gained through

considerable study of linguistic phonetics and psycholinguistics (Fraser 2003:

221).

Applying an understanding of word stress, speech rhythm, intonation, and other prosodic

information as well as contextual clues can aid in the accurate transcription of difficult to hear

phrases. Such linguistic understandings are part and parcel of a professional linguist’s field of study

and research. Assumptions should be avoided when transcribing speech for legal purposes, and in

the end, where any transcriber is unsure of what has been said they should clearly indicate this in

the transcript.

Accent and dialectal variations

Assumptions about what is said in a recording may also be found in transcriptions of speakers whose

native language is not English or of those who use a ‘non-standard’ or ‘regional’ dialect of English.

When interacting with non-native speakers, native English speakers often subconsciously fill in

certain features such as missing articles (a, the, an) or conjunctions (and). It is only when the

grammatical formation used by a non-native speaker is particularly unusual that the native speaker

might suddenly become more conscious of the differences and seek clarification.

Transcribing the language of non-native speakers of English can be challenging for unskilled

transcribers. In these situations it is extremely important to capture how the speaker uses the

grammar and not to correct or fill in any perceived errors. Furthermore, many people suffer an

‘accent bias’ when they listen to English spoken by non-native speakers, and this kind of bias can

impede comprehension and if held by the transcriber may affect the amount of spoken language

captured in the transcript. A linguist who is used to listening to, analysing, or transcribing non-native

English will be able to capture more of what has been said, and will likely provide a more objective

transcription. A transcript which does not represent the grammatical patterns of a speaker is not an

accurate representation of the speech and is going to be questionable as a form of evidence.

Correctly representing non-native English speech could be important if comparing two transcriptions

of the same speaker, if confirming that different recordings are of the same speaker, or if asked to

assess the English proficiency level of a speaker. Where there may be difficulties in distinguishing

whether an article or conjunction has been used, a consideration of grammatical patterns used by a

specific speaker across the recording can be checked for comparison or confirmation. A knowledge

and understanding of speech rhythm may also be drawn on as it can give insights into the number of

syllables used in any utterance, and whether this indicates the presence of minor unstressed words

such as articles, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions or the like.

Assumptions about ‘correct grammar’ and accent bias may be carried over to transcribing native

speaker dialectal variation or the speech of children. Grammatical patterns, such as ‘I seen’, ‘we was

took’, ‘he brung it’, must be transcribed without modification so that an accurate picture of a

person’s speech is presented.

Children’s speech may also include ‘incorrect’ or ‘developing’ grammatical forms, as well as

developing pronunciation patterns. Guasti’s (2004) research on language acquisition in children up

to five years old and across several languages shows that children may interpret certain structures

differently from adults, and Clark’s (2003) work on first language acquisition highlights some of the

phases, such as overregularization of irregular noun and verb stems, that very young children go

through. Assumptions about what a child has said during an interview should not be made. Rather,

it is important to have an understanding of the kind of variation possible in the speech of children in

order for the transcriber to produce an objective and accurate transcription.

Overlapping speech

Indicating overlaps or interruptions in spontaneous conversation indicates the progress of the

interaction. But the skill involved with this aspect of transcribing spontaneous speech is generally

not in the repertoire of a secretary or audio expert, or unskilled transcriber. Linguists who work with

naturally occurring speech use specific conventions for showing these interactive features, even

where multiple speakers are involved. Research into conversational styles has shown that

overlapping and interrupting speech can point to such things as a speaker’s cultural or regional

background, or their role or relationship with the other speakers in a situation (see Tannen 1984).

This kind of information could be useful when building information about the identity of a speaker in

a covert recording. The type of overlapping or interrupting may also be of importance. Speakers may

engage in cooperative or obstructive overlaps and interruptions (Tannen 1984; cf. Jefferson 2004)

and analyses of this may also provide evidence of support or intimidation in the interaction, which

may be of significance in a case.

In formal interviews between police and suspects or witnesses, the representation of overlapping or

interrupting speech can provide evidence for possible ‘oppression’ of suspects (see for example

guidelines for PACE interviews at www.hse.gov.uk), or intimidation of vulnerable witnesses, such as

child witnesses (cf. Aldridge & Luchjenbroers 2007).

Punctuation

Punctuation is an extremely important aspect of a good transcription because it can provide

information related to the manner in which something is said, and can help to disambiguate certain

meanings. For instance, commas can be used to indicate pauses, or to indicate separation of items,

or even to indicate specific meanings. The different meanings of the following utterance can be

conveyed through the use of commas:

‘My sister who lives in Canberra was caught shoplifting.’

‘My sister, who lives in Canberra, was caught shoplifting.’

The first example is punctuated as a restrictive relative clause. In speech, there would be two likely

readings. One would place emphasis on the syllable ‘shop’ in shoplifting. The other would place

emphasis on the syllables ‘Can’ in Canberra and ‘shop’ in shoplifting. In either case, the meaning

would indicate that the speaker is defining which sister was caught shoplifting – i.e. the one who

lives in Canberra. Thus we can infer that the speaker has more than one sister. One who lives in

Canberra and at least another who lives somewhere else.

In the second example, the punctuation indicates a non-restrictive relative clause. In this case, the

information ‘who lives in Canberra’ is offered as extra information and not as defining information.

When spoken there would be three points of emphasis – one on the syllable ‘sis’ in sister, one on

‘Can’ in Canberra and one on ‘shop’ in shoplifting. We can infer that the speaker has one sister and

that she lives in Canberra. Such information would, of course, need to be verified, but the use of

correct punctuation in these instances is extremely important for conveying the two different

meanings.

There are other examples of where punctuation can make a crucial difference in meaning. For

instance, consider the following exchange:

A: John’s in the car.

B: He’s in the car is he alright

There are at least two ways in which this sentence could be punctuated, but only one way according

to how it was said in the recording. Let’s consider the following two punctuation choices.

1) B: He’s in the car. Is he alright?

2) B: He’s in the car, is he? Alright.

By choosing the first punctuation, the transcriber is indicating that the speaker is confirming that

John is in the car, and then asking whether he is alright. The second choice of punctuation indicates

that the speaker is confirming that John is in the car, and then using a discourse marker, ‘alright’ to

indicate that this part of the exchange is over. These two different punctuations result in very

different meanings. An understanding of the relationship between spoken language, intonation,

meaning, and punctuation is important in producing an accurate transcription. Many lawyers do not

have the time to constantly go back and check the transcript against the recording. Therefore, it is

extremely important to get the punctuation right so that it most accurately represents what has

been said.

Transcription Conventions

Another issue that bears mention is that to do with transcription conventions. Linguists are used to

providing a set of conventions that indicate various features of a transcript. Such features include:

pauses, overlaps and interruptions, unclear speech, and special meanings conveyed through

emphasis or other paralinguistic devices. A standardised set of conventions for transcriptions used

for legal purposes would mean that lawyers could easily understand the features of the transcript. A

set of standardised conventions would save time in figuring out what the individual transcriber has

presented, but I would not suggest that the conventions be as detailed as some linguists use. A

lawyer needs to be able to read the transcript easily, and not be sorting through conventions that

require too much explanation. Where sections of a transcript may require greater detail for

presenting evidence a linguist may re-transcribe those sections with more detailed information with

regard to such things as pausing or specific paralinguistic features. In such cases, consultation with a

lawyer to explain the specific markings on a transcript would be required. A sample set of basic

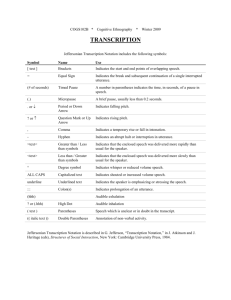

transcription conventions is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1: Some Basic Standardised Transcription Conventions

Convention

Meaning

[

Square brackets mark the start and end of overlapping speech.

underlining Underlining indicates special emphasis on a syllable in a specific word.

CAPITALS

Capitals mark extended speech that is perceived to be louder than the surrounding

speech.

a::nd

Colons show degrees of elongation of the prior sound; the more colons, the more

elongation.

{LAUGHTER} Additional comments regarding what is going on in the conversation are

mentioned in curly brackets.

(?)

Unclear speech is indicated by the use of parentheses around a question mark.

Transcription Costs

There are many transcription companies, and individual transcribers who offer their services at very

competitive rates. They detail how they calculate their costs – usually by 65 characters per line –

and they may even tell the customer that they are not paying for the ‘spaces between the lines’.

There are of course, some excellent transcription companies around, but I believe that a focus on

turn-around times and costs are trivial concerns compared with the importance of objectivity and

accuracy in the context of a criminal or civil trial. In the end, lawyers might find that a professional

transcription is particularly cost-beneficial.

Conclusion

A transcript can be a very powerful and valuable piece of evidence in a trial and certainly in the

investigative stages of a case. In preparing and presenting evidence in court, a lawyer requires a

transcript that can stand scrutiny and can be referred to with confidence. The consequences of

using a poor transcript can be very grave indeed, and lawyers need to seriously consider the

advantages of using a professional transcription (i.e. one done by a qualified linguist) in light of the

danger of losing their case because of a poor transcription.

References

Aldridge, M. & Luchjenbroers, J. (2007) Linguistic Manipulations in Legal Discourse: Framing

questions and ‘smuggling’ information. The International Journal of Speech, Language and

the Law 14(1): 85-107.

Clark, E. (2003) First Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, H.H. & Fox Tree, J. (2002) Using uh and um in Spontaneous Speaking. Cognition 84: 73-111.

Fraser, H. (2003) Issues in Transcription: Factors Affecting the Reliability of Transcripts as Evidence in

Legal Cases. Forensic Linguistics (now the International Journal of Speech, Language and

the Law) 10(2): 203-226.

Guasti, M.T. (2004) Language Acquisition: The Growth of Grammar. MIT Press.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1985) Spoken and Written Language. Geelong, Vic.: Deakin University Press.

Jefferson, G. (2004) A Sketch of Some Orderly Aspects of Overlap in Natural Conversation. In Gene

Lerner (ed.) Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation 43-59. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins.

Nyyssonen, Heikki (1995) Grammar and Lexis in Communicative Competence. In Guy Cook & Barbara

Seidlhofer (eds.) Principle and Practice in Applied Linguistics: Studies in Honour of H.G.

Widdowson 159-170. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Olsson, J. “Why is it important to get better transcripts of interviews?” from:

www.thetext.co.uk/forensic_transcriptionfaq.html (Accessed 5th May 2009).

PACE interviews (UK)

1) for admissibility of interviews as evidence see:

http://www.hse.gov.uk/enforce/enforcementguide/investigation/witness/admissibility.htm

(accessed 5th May, 2009).

2) For Guidelines for Interviewing see:

http://www.hse.gov.uk/enforce/enforcementguide/investigation/witness/questioning.htm

(accessed 5th May, 2009).

Swerts, M. (1998) Filled Pauses as Markers of Discourse Structure. Journal of Pragmatics 30(4): 485496.

Tannen, D. (1984) Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk Among Friends. Westport, Connecticut: Ablex

Publishing.