resettlement action plan

advertisement

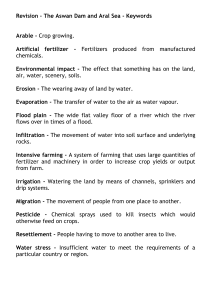

YUSUFELI RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN CONCEPTUALIZING THE RESETTLEMENT ISSUE AND EVALUATING THE ADEQUACY OF THE CURRENT TERMS OF REFERENCE AYSE KUDAT SOCIAL ASSESSMENT AUGUST 30, 2000 2 Executive Summary The Yusufeli hydropower project presents a set of unique resettlement challenges. Many of these are addressed in the current terms of reference (TOR) for the ongoing resettlement action plan (RAP). Several measures would be needed to upgrade the work that would result from the current TOR so that the resulting RAP could be compatible with international standards. To do so would involve relatively modest additional data collection and the support of a small team of specialists experienced with international practice. To ensure that the current RAP is compatible with international standards the resettlement issue and the “affected populations” could be defined more broadly to cover: (ı) all the communities of Yusufeli that will be adversely affected by the inundation of the road and other infrastructure inundation and (ıı) the unique role of the town of Yusufelı ın the overall impact area. The current TOR, with respect to its socio-economic surveys, only includes communities whose houses and/or cultivable lands will be inundated. Although a larger percentage of the communities will be covered through headmen interviews, insufficient focus has been devoted to the impact of the significantly modified road infrastructure on the county as a whole; To carry out a broader assessment of social costs of the Yusufeli dam, alternative road infrastructure proposals should be obtained and evaluated. Similarly, the cost of replacing the road infrastructure and/or building one that allows only partial connectivity within the settlements forming the county should be evaluated. The current TOR could be expanded with regard to this; The present uncertainly with respect to the replacement of the road infrastructure affects people’s resettlement preferences. Should it not be possible to develop a concrete final infrastructure plan at this stage, a contingent analyses with respect to these preferences could be carried out. The current TOR does not include contingent analysis nor does the current team have experience in this relatively less well-known methodology; Because the needed work could be based on a small but carefully selected sample, the financial and time costs would be minimal. If analytical expertise could be obtained, the work can be carried out in a short period of time; Although there are many proposals for the re-construction of the Yusufeli town, the proposal of the town people to build it in nearby higher elevations is excluded from the official lists available. All proposed sites, including at least one suggested by the people of Yusufeli, should be evaluated with respect to their environmental feasibility, water availability, and social appropriateness. There is need to launch the relevant preliminary studies without further delay as their results should be shared with the people. If the people are informed in a convincing manner that the financial and the environmental costs of rebuilding the entire road infrastructure as well as creating a new town in higher 3 elevation from the present town would be prohibitive, a large percentage of the current resettlement preferences could be modified; Income restitution is the principle behind the international resettlement standards and will be an important challenge for the Yusufeli project. There is insufficient directive within the current TOR to allow a comprehensive investigation of current income, especially from non-agricultural sources. Equally important is the lack of specifications in the TOR for programs to establish future income, especially given the role of transport and gravity irrigation in current farm operations and of access to pastures for livestock. Thus, it is difficult to judge whether the consultants will develop well researched and adequately costed proposals for income restoration. Should the draft RAP be inadequate with respect to income restitution issues, the work could be upgraded with support of an economist with relevant experience; A major gap in the current TOR concerns the comprehensive calculation of all assets, incomes, infrastructure, public facilities, etc., to be lost (social costs of the project). Also lacking is the calculation of replacement costs depending upon alternative scenarios. Measures have already been proposed to the team working on the current TOR to remedy these gaps (Annex 1). Any future inadequacy with respect to the output would not be result from data gaps but from insufficient data analysis. This, too can be remedied by a top resettlement specialist; The current TOR can also be strengthened with respect to institutional issues concerning the resettlement plan design and implementation. Currently, a large number of public agencies, ranging from DSI, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the General Directorate of Rural Services, and many others, coordinated under the Provincial Governor, are involved in resettlement implementation. This situation, in the past, hindered the effective and timely delivery of the required infrastructure and other resettlement arrangements. There is need to provide guidance concerning realistic institutional modifications and innovative coordination arrangements that would allow the effective and efficient implementation of a RAP. DSI is already reflecting on these issues and could itself complement the current RAP team to outline workable implementation arrangements in the RAP; The current TOR also provide little guidance concerning the need to design a sustainable participation and information/communication (I/C) action plan. Rather, several requests have been made to organize participatory meetings to solicit people’s preferences for the preparation of the RAP. Although these is a high level of people’s participation in the resettlement agenda, the TOR is not explicit in the design of a sustainable participation and I/C strategy. This deficiency too can be remedied through support of a resettlement specialist with extensive international experience; and 4 The Yusufeli survey instrument, which was based on another dam with very different resettlement challenges, required substantial modification and pretesting before implementation . The required changes are now in place after the review this consultant provided (Annex 1). To remedy the deficiencies will not be difficult if a team of internationally recognized specialists (one in the following fields: transport/marketing, quantitative social science/report coordinator and a senior economist) together with two outstanding data analysts are recruited in addition to the existing consultants working in the field. Much of any additional data that might be needed could be obtained by this team at a minimal cost and the new analysis/write-up could be completed in a short period of time with a good team. 5 ISSUES PERTAINING TO THE PREPARATION OF THE YUSUFELI DAM’S RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN AS PER INTERNATIONAL (WORLD BANK) STANDARDS1 1. The Yusufeli Dam is one part of an integrated river basin development that can increase Turkey’s current hydroelectric capacity by more than 25% and make a major contribution to help meet the country’s electricity needs in the future in a way that is both non-polluting and uses the country’s renewable natural resources. The construction of the Yusufeli dam will also make a major contribution to the life of other dams now under construction on the Coruh river. However, there are substantial resettlement issues that need to be met and can be met if a basin wide approach is taken to resettlement, a resettlement action strategy (RAS) and a resettlement action plan (RAP) are prepared, and secure implementation arrangements are put in place, including a commitment to allocating budgetary resources in a timely and coordinated approach. RAS and RAP 2. This note will focus on the RAS and the RAP based on a four day site visit to assess (i) whether the RAS is accurately formulated; (ii) whether the terms of reference (TOR) of the RAP consultants are adequate to meet international standards; and if not (a) what is missing and what expertise is locally available to fill the gaps; and (b) how the current consultants could be guided to focus on priority areas; and (iii) the quality of the resettlement survey instrument that the consultants will use to collect basic and baseline data. The survey instrument. 3. In view of the quick response requested by DSI concerning the survey instrument, the consultant sent immediately after the site visit an assessment of the survey instrument which is attached as Annex 1. Basically, the proposed survey instrument mirrored that used for the Ilisu Dam whose resettlement challenges are very different from that of Yusufeli. The consultant has made suggestions for changing the survey instrument and for focusing on areas of concern for Yusufeli. A revised survey instrument is now being prepared to be pre-tested in Yusufeli to confirm its effectiveness. 1 Acknowledgement: The preparation of this note is made possible through the support of the regional office of DSI. The regional director, Mr. Mehmet Kilinc, has generously provided information and logistic support. His staff traveled long hours to help gather information. 6 The resettlement challenge of Yusufeli: RAS 4. Although there is an intimate relationships between a RAS and a RAP, many TORs for RAP lack a strategic framework. The Yusufeli TOR are no exception in that it lacks a clear strategic objective thats fit the unique situation of Yusufeli as a community of one town and some 60 villages, each with hamlets and pastures, all of which are intimately connected to the town for historical, social, economic and geographic reasons. It might be useful to set the scene for the Yusufeli resettlement challenge since the priorities to be investigated are not ones that are common in Turkey and in the world in that: The most important impact of the Yusufeli Dam reservoir on the largest number of people – perhaps over 30,000 – may well deal with the fact that the road transport network, which is now extensive along the entire main river and its tributaries and which is critical to the social and economic fabric of the impact area. A resettlement strategy that acknowledges the central priority of transport is so unusual that it would need extensive justification. In this context it is important to note that the Yusufeli dam does not merely affect the settlements that will be inundated by the dam reservoir (which would have been typical for a great majority of dams) but might adversely impact all of the settlements that consist of the county (ilce) of Yusufeli. The transport network that will be inundated by the dam poses the risk of isolating a large number of villages that will not be inundated but will lose their transport linkage to the rest of the communities; The second most important impact of the dam appears to be the inundation of the productive agricultural land in the immediate impact area, much of which has been “built” by farm families through transport of soil from elsewhere and which uses gravity irrigation for intensive cultivation of mainly vegetables and fruits with some cereals, especially rice in one area. A resettlement strategy would therefore have to put priority on income restoration and, if people remain in the immediate area, on pump rather than gravity irrigation; The destruction of housing, usually the most important aspect of resettlement, may be, in the case of Yusufeli, important, but not as important for the RAP as a whole, as the transport and agricultural aspects, the former of which require substantial investment while the latter may require a refocus on farmer skills. The situation arises because many households will lose their transport links and agricultural land which will be 7 inundated but not their homes, which are often built on higher ground that may be above the reservoir level; The central role of the town of Yusufeli (ilce merkezi), with a population of between 5,400 and 9,000 according to different sources, presents another unique feature of the RAP. It is essential that the RAP evaluate through a process of social assessment and stakeholder consultation the role of Yusufeli in the economic and social fabric of the area and the minimum requirements from government for the creation of a replacement that would fulfill the economic and social functions of the present town. Clearly, without the current transport network, the future economy of the town will be undermined. Likewise, without the continued economic support from the town the villages whose transport links to the town will be lost may experience income loses; Because the people of the county appear to “demand” in very strong terms that their “unity” as a county be maintained, the re-construction of the transport network and of a new town with all the amenities that the present town may well impose unusually high resettlement costs to the project. This demand may be impossible to meet technically and may present high environment costs given the characteristics of the terrain. The people claim that they would stay in the area if their demands for “unity” are met; yet, the county has displayed an enormously high outmigration rate over the past decades despite its “unity”. This has only slowed during the last year because of the fear of the earth-quake that resulted in large scale damage in towns, such as Adapazari, where the immigrants from Yusufeli concentrate. The people believe that the fear of earth-quake, on the one hand, and the enhanced opportunities for employment that would result from the construction activities associated with a series of dams under construction in the region would help reduce outmigration from the Yusufeli county. Thus, rather than the expected high financial costs of reconstruction of the road infrastructure, the development of the region itself might create the social and economic opportunities that especially the townsmen of Yusufeli are seeking. The nature of the resettlement issue of Yusufeli: loss of social capital resulting from dam impacts on transport infrastructure. 5. There is increasing concern with social risks of large scale investments among the international loan agencies as well as the governmental organizations responsible for loan guarantees (Export Credit Agencies-ECAs). Civil society is also better organized to prevent the large social costs of development activities from being shouldered primarily by a relatively small number of people. The awareness of risks is especially high in the hydropower sector, yet actions taken to reduce them continue to be weak around the world and in Turkey. 8 6. The resettlement activities associated with large-scale projects are usually under-resourced both financially and in terms of human resources. Thus, the single most important criterion in making a judgement concerning the appropriateness and adequacy of a resettlement plan continues to be a realistic assessment of its costs/implementation potential. Plans can be made to look good on paper and may even reflect good intentions with regard to their implementation. Yet, institutional fragmentation, inadequacy of funding, changing government priorities during the course of the project may all result in the neglect of resettlement activities. Although the international community requires that resettlement plans be prepared using World Bank standards, a large number of projects financed by this organization also lack rigor in their preparation. The World Bank thus continues to cancel its funding for infrastructure projects when planned resettlement activities are not implemented. There are indications that ECAs will provide funding for development investments conditional to their sustained care for social and environmental costs. 7. The major risks consist of: Landlessness, Homelessness, Marginalization, Food insecurity, Increased morbidity, Loss of common property resources, and Community disarticulation. It is rather rare for specialists to be able to identify resettlement situations where the major risk is community disarticulation. This is a unique feature of the Yusufeli case and sets it apart from other hydropower projects. In Yusufeli there is a high “perceived” risk of community disarticulation. This perception has a concrete reality associated with the loss of the transport network that now defines the Yusufeli community. 8. Before reviewing the other risks typically associated with dam projects, it may be helpful to explain what the risk of community disarticulation means in the concrete case of Yusufeli. What makes Yusufeli unique is its enormous social capital and the pride its people take in being from Yusufeli (“Yusufelili”)2. One thing that everyone agrees upon is the presence of enormously high levels of trust in Yusufeli as the following comments by the people of the town testify: “No one commits crime.” “The prison is built to be vacant”. 2 The regional director of DSI explained to the consultant that he was a high school student when he first heard a radio program about Yusufeli, about the character of the town: honesty and hard work. To date he has not forgotten it. When the TV was introduced to Turkey and then newly married, he watched another program on Yusufeli. He and his wife then knew they had to visit the area and they did. Decades later, ironically, he was appointed to his position in Artvin at a time when the Yusufeli community may be fragmented. 9 “No store will take the goods they display on the street indoors at night”. “No one from Yusufeli would every want to change their birth certificate to another location in Turkey regardless of how long ago they might have migrated; being from Yusufeli is the single greatest reference for honesty that anyone can have”. “Every employer would feel lucky to have an applicant from Yusufeli”. “People from Yusufeli would dig into rocks with their hands to rebuild their community as long as they are not denied the opportunity to do so”. 9. Thus, it is the risk of loosing social capital, trust, presence of strong social ties that the people find particularly threatening. This is more so in the town than in the village communities since the social capital is translated3 into profitable business in the town. To maintain the county and, more importantly, to expand the social and economic base of their community, a large number of other villages, among them a previous county center (ilce merkezi), came forward offering their settlements to serve as the new center of Yusufeli county. However, in each the villagers say that “if the center could be built near the current town of Yusufeli, that would be fine”. Needless to say, the risk of community disarticulation is more strongly felt within the town of Yusufeli than elsewhere primarily because a large percentage of the town population makes a living by serving its periphery 10. Yusufeli is more than the town that serves as the county center: it is a community of 60 settlements closely connected to one another. Over the years the connectivity between each of the settlements has improved through transport infrastructure and the town of Yusufeli came to be the center (ilce merkezi) because the previous center did not provide the same connectivity as the present center. The center and periphery is connected both through strong economic ties and through well-knit social ties. The town itself is composed primarily of migrants from the periphery, many of whom appear to maintain double residents in the town and in the village. Should the new Yusufeli center not be established in close proximity to the present center but a new location is chosen in one of the extreme points of the five different and otherwise disconnected valleys the town of Yusufeli itself will largely be fragmented and many of its residents will migrate to areas outside the region once they receive their compensation payments. Thus, avoiding the risk of community disarticulation is equated with the rebuilding of the existing transport network that enables all the villages and the center to maintain a “community”. A similarly strong sense of county solidarity cannot be found elsewhere in Turkey and has evolved in the case of Yusufeli over time through improved transport network and migration to the county from the periphery villages. 3 In this sense also Yusufeli is a textbook case: the central settlement (town) is truly the center of all settlements that compose the county. 10 11. Of the remaining risks, the loss of access to common property resources, of pastures, forests, etc., also appear important with significant income implications. Marginalization is likely to be a high risk for some of the partially affected settlements and those that have been left outside the scope of the Terms of Reference (TOR) now under implementation. Severe health problems and food insecurity may not be important risks and the present TOR specifically aims at the establishment of the risk of homelessness and landlessness. Preliminary interviews suggest that unlike other resettlement situations, both homelessness and landlessness are perceived as less important. First, a great many people have already migrated from the region and some have multiple homes. Many also have close relatives elsewhere in Turkey and a large number continues to make a living from seasonal labor, working about half the year in western Turkey and returning home the rest of the time. Secondly, there does not appear to be scarcity of land in the area as evidenced by some 7 villages coming forward to host a whole town and being able to show the availability of sufficient land. The villages that will be inundated also point to the availability of village lands in mezras or pastures and are willing to take up residence there provided that the transport network will provide them easy access to other centers. 12. In conclusion, the risk of loss of social capital or community disarticulation, loss of access to common property resources as well as marginalization appear to be high perceived risks of the dam construction. There risks are not addressed in the TOR under implementation. As such the resettlement issue of Yusufeli is not adequately addressed. The loss of social capitalandcommunitydisarticulationhavemajortangible and measurable implications. For instance, all business in Yusufeli town takes place on the basis of trust; most customers take goods with a promise to pay and most shop keepers can show their books with merely a list of expected payments; no legal transactions are needed. The people note that the breaking up the unity of the county will severely reduce their incomes from commercial activities and they will, thus, have no reason to stay. The farmers will likewise be affected in their ability to obtain farm inputs and to market their goods even though their homes and/or land may not be impacted. The redesign of the draft surveys and other research instruments might offer a remedy to this issue. DSI is now working with the Consultants to make the necessary changes based on this consultant’s comments (Annex 1). 13. As a consequence of casting the resettlement issue in the typical sense of risk of inundation of homes and land, the affected populations have also been somewhat narrowly determined in the current TOR. Given the scope of the current TOR, this issue might not be fully remedied without additional resources. The current team, with support from international experts and some local staff, should be able to fill this gap without incurring excessive expenses. Current TOR Objectives and Compatibility with the International Standards 14. The international standards for resettlement action increasingly require a “development” approach. As such the purpose is not merely to compensate the people for their assets and finding available land and relocating those seeking state 11 support. The internationally accepted World Bank standards minimally require the following: Avoiding or minimizing involuntary displacement. Restoring and improving incomes and living standards. Allocating resources and sharing benefits. Moving people in groups. Promoting participation. Rebuilding communities. Protecting customary rights and access to common property resources. Establishing sound institutional mechanisms for the implementation of the RAP. Preparing essential instruments to address resettlement issues. 15. Of the above principles some have been incorporated into the current TOR, and measures can be taken to ensure that the rest is also done with additional resources and know-how. The following section provides some proposals to upgrade the current TOR to international standards. To do so, we shall start with a discussion of the adequacy of essential instruments incorporated in the TOR. These instruments consist of: A baseline income survey. A detailed resettlement plan. A relocation timetable corresponding to advances in dam construction. A distinct budget for resettlement. 16. A baseline income and socio-economic survey is included in the current TOR. However, the TOR is insufficiently specific to establish direct and indirect incomes, and incomes from non-agricultural activities. The first draft of the socioeconomic surveys provided by the Consultants was particularly weak in this regard and comments were provided (Annex 1) to remedy this situation. Perhaps a more important deficiency with regard to income estimates relates to the fact that the examination of the interrelationship of income levels, transport and marketing networks, and social capital are not requested in the TOR. This be done with a more experienced, but small, team. 17. The TOR also asks that a Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) be prepared by the Consultants. However, insufficient guidance is provided as to how this should be 12 done4. In addition, the TOR does not provide an adequate definition of the “affected populations”. There is an implicit sense that the RAP would basically deal with the resettlement and income restoration issues of those who seek support from the state for resettlement. If the RAP concerns itself merely with this group, it may not be acceptable by international standards. If, on the other hand, the RAP is to deal with all the people whose land and/or residential areas will be fully or partially inundated, the TOR provides little hint with regard to the planning of income restoration problems to be confronted by the people who will ask for cash compensation for their assets (and this ratio may be higher in Yusufeli than in dams elsewhere in Turkey. In short, there is little focus, if any, on the RAP on the selfsettlers. This is yet another area of gap that needs to be filled to upgrade the current RAP to international standards. 18. As mentioned above, confining the notion of “affected populations” merely to those whose lands and/or homes will be inundated by the dam reservoir will likewise not meet international standards. This is because the inundation of the transport network by the reservoir is likely to cause a dramatic fall in incomes and living standards for some of the communities of Yusufeli. The determination of “affected populations” can only be done once the arrangements concerning the replacement of the transport network are completed; before than neither the affected populations nor people’s true preferences for resettlement can be established. 5 19. There is also need to undertake a legislative review and determine whether or not the current Turkish laws on expropriation and resettlement would allow a broader definition of “affected populations” as defined above so that communities that will lose their transport infrastructure and market connections can ask for For instance, under D.2 of the TOR it is mentioned that “for the population affected by the dam and based also on the socio-economic surveys, agricultural and economic investment alternatives, technical requirements and their financial costs will be research and included in the plan”. D.3 adds that other alternative income opportunities will be identified. “ By taking advantage of the natural and touristic characteristics of the region, eco-tourism, hunting, fishing, hand-crafts and other activities will be investigated and detailed proposals will be made to provide income for those families to be resettled”. Also, “economic, financial and cost analyses will be carried out to provide the families to be resettled with advisory services, monitoring and evaluation”. Finally, the TOR mentions that “in the resettlement areas” and “to ensure that families affected are at least as productive as before and reach a higher standard of living after the dam is completed, research on employment will be carried out, and studies will be conducted to provide economic and social rehabilitation, especially to create side income for women. Special programs will be designed for the youth and the elderly”. No addition guidance is provided as to how, with what detail and through what types of investigative methods such programs will be designed. An examination of previous RAPs shows that these consist merely of a similar list of activities without any feasibility work. For the Birecik dam, for instance, the program suggested consisted of a general list: poultry, hand-crafts and carpeting, eco-tourism, etc., and none of these has been put in place despite the fact that the dam construction has now been completed. 5 The implication of which particular definition of affected populations would be used is of critical importance. If only those who seek government support are provided assistance, there may be as few as 1,000 people to be concerned with. If, on the other hand, the definition includes those who will lose land and/or housing, the number is about 13,000-15,000 depending upon how the town population is defined. If, however, the country itself is accepted as the definition of those who are affected, the population that the RAP is to be concerned with may reach 31,000. 4 13 resettlement benefits6. This deficiency can be remedied either by the current Consultants working on the RAP or be done by the supplementary team to upgrade the RAP to international standards. 20. For reasons that should be clear by now, a relocation timetable, requirement for a RAP of international standards would be difficult to prepare under the current TOR in a realistic manner; but once the alternative transport and county center reconstruction costs are estimated and people are consulted, the preparation of the timetable would not take much time. 21. The most critical gap in the current TOR is the request for and guidance on the preparation for a fully costed resettlement action plan. The relevant costs should include Expropriation costs Infrastructure replacement costs, including transport7, water supply, energy, Resettlement costs 8 Cost of advisory services, job creation programs, skills training programs and other guidance/services to be provided to all affected populations to ensure that incomes and living standards are improved or, minimally, restored. Cost of re-building a county center with schools, municipal buildings, hospitals, police station, prison, and many other facilities typically available in a town. Why is the cost of resettlement important for the international community? 22. The cost of land acquisition and resettlement is an integral part of the overall cost of dam projects. Yet, most dam projects refer to engineering cost. And the cost effectiveness of projects or the energy obtained from them is calculated on the basis In both the villages and in the town of Yusufeli people repeatedly ask this question. “If the unity of Yusufeli is lost, some villages are marginalized and isolated, there is risk of survival. How can some 20 villages survive if their roads are lost? Where would they go? If the transport network is not going to be replaced, it is best that Yusufeli country is fully expropriated, the area is declared a disaster area and converted into a national park”, demand many. Others merely ask whether this would be possible so that the whole county pack and go away. 7 Alternative transport options, especially in the road sector for resettlement within the general Yusufelı impact area, is needed quite quickly as it would be an important area to be discussed in a participatory way with the affected population. 6 8 The resettlement housing/land is provided only to those who seek state support. This is often requested by landless households and their numbers are likely to be very small in Yusufeli where most families have assets for which they intend to get cash compensation. These families could obtain cash compensation as well as receive credit for resettlement housing if they request. However, they are not informed of this potential that would allow them to resettle in groups of a minimum of 30 households. This resettlement model, largely inapplicable in other parts of Turkey, promises good results in Yusufeli where land availability does not appear to be a problem. There is need to pursue this alternative in a timely manner. 14 of the construction costs alone. The resettlement costs are often substantially underestimated and confined to a portion of the expropriation costs. Because a specific and comprehensive budget is not available and/or inadequately covered, international agencies concerned with resettlement issues hesitate to fund dam projects (or others causing resettlement). Moreover, in most resettlement situations, multiple actors and agencies are involved, each with a different mandate, set of priorities and budget. If the contributions that each is to make towards resettlement are not budgeted for, the overall required action will not take place. Thus, in the case of Yusufeli, the road infrastructure will have to be partially or totally replaced and this will have enormous cost implications. If these costs are not included in the total budget of the dam’s resettlement component and concrete evidence is not provided that the required investments will be made, the credibility of the RAP will be severely reduced. 23. The cost estimates and related gaps in the current TOR can also be closed by by a competent team of specialists, complemented by an expert familiar with the budgeting process in the Turkish context as well as with the institutional histories of the public agencies involved.9 Meeting other international standards for resettlement 24. Minimizing involuntary displacement. Although this is a crucial requirement for a RAP, the fact that most resettlement plans are prepared subsequent to the technical plans hinders the interaction of social and technical engineering elements. This is the case in Yusufeli as well; there is little that can be done to actively pursue other dam site alternatives taking social and environmental issues into consideration. However, the people could be more thoroughly informed of the alternatives considered10. 25. Restoring/improving incomes. The current TOR incorporates this concern. As mentioned earlier, this critical issue, may not be treated to international standards for several reasons: (a) the TOR’s specification of the affected populations is unsatisfactory; (b) most of the income restitution directives are given only with regard to those, probably a minority, that might request state support for resettlement; (c) a comprehensive study of the income profile of the affected households, especially those in the town, is complex and is made difficult11 given the budgetary constraints 9 This is necessary so that unrealistic expectation are not incorporated in the RAP budget. For instance, the experts may calculate that the transport infrastructure replacement costs to be $800 million, or, $100 mıllıon per annum to be carried out by the road authority whose total annual budget for the province of Artvin might have been less than 10 percent of this. Thus, knowledge of budgeting processes of individual agencies would be important. 10 A large group of representatives has sought an explanation from the government concerning the resettlement implications of alternative siting possibilities. Their request has reportedly been responded to with an official letter which explains that other alternatives were considered and were found to be highly unsatisfactory from a technical perspective. Yet, there appears to have been no discussion of the resettlement implications of these alternatives. 11 This could have been possible if the Consultants had several top economists in their team. 15 of the TOR; (d) modeling alternative scenarios for income restoration requires extensive experience as well as familiarity with likely development outlooks of the region. The current team is not likely to have the required skills in this regard; (e) a standard list of activities that might hypothetically restore current incomes is unlikely to satisfy credit agencies. An additional team of specialist, as defined above, would be needed to meet this important criterion for an internationally acceptable RAP. 26. Allocating resources and sharing benefits. This issue has been excluded from the current TOR and would require some consideration. This is particularly so since several proposals have been tabled, including from officials, to allow the affected populations to share a small percentage of the energy revenues from the dam for a certain period of time. This can be done by a local energy economist. 27. Moving people in groups. The TOR doesn’t mention this although existing legislation says that for those who request state assisted resettlement, this will be done in groups of at least 30 families, an inflexibility that is unfortunate. Since it appears that many of those who are fully affected will not choose state assisted resettlement – although this needs to be verified by the Consultants, moving people in groups may not, in fact, be a major challenge for the RAP. In any case, the existing team should be able to deal with this subject without additional input. For those who do choose state assisted resettlement, early planning for and implementation of specific resettlement sites will be important, especially so that resettlers are provided with new homes and sustained income opportunities well before their existing homes and livelihoods are inundated by the Yusufeli reservoir. 28. Promoting participation. In other situations around the world, the establishment of a specific participation strategy and its early implement, including during preparation of the RAP, has been important in reducing suspicion and ignorance concerning the costs and benefits of dams, and in shaping resettlement policies and actions. At present, the TOR essentially confine “participation” to holding meetings, largely for information purposes, and focus groups. It is clear that the affected people in Yusufeli wish to have an early opportunity to be: (i) informed about the current status and future plans of the Yusufeli Dam and of how they will be affected; (ii) consulted about areas12 of the dam project that affect them – areas that they broadly define ranging from issues of resettlement to those of employment possibilities during and after dam construction; and (iii) allowed to participate in the design of the RAP and in its implementation. There is today a high degree of suspicion among many people and leaders of Yusufeli about “what is being done to them”, and it is the view of this consultant that this suspicion derives more from lack of true communications and information than from the reality of the situation. It is therefore of great important that the TOR be enhanced using international best practice to develop a sustainable participation strategy that defines how the authorities wish to approach the involvement of affected people in the Yusufeli Dam The use of computer sımulatıon, usıng GIS data and technology readıly avaılable ın Turkey that can be projected ın vıllage settıngs, has been ınvestıgated by the consultant and could be a powerful tool ın establıshıng a process of consultatıon and partıcıpatıon wıth affected stakeholder groups. 12 16 process and a participation action plan that will be both a sustained part of the RAP preparation and of its implementation. This strategy/plan needs to include: a communications/information program that will be immediate, sustained, transparent and cover all aspects in which affected people are interested; a consultation plan that provides two-way flow of information, both to the affected people and to the authorities, with independent outside facilitation to ensure that consultation is effective; and a participation plan that really does allow affected people to have a say in how their future is determined with Turkish resettlement laws and international best practice. The required work is additional to the current TOR but can be completed by the above mentioned small expert team. 29. Rebuilding communities. Communities that are affected and those that relocate need to be rebuilt not just physically but socially and economically. This has been discussed at length above and is the essence of the concerns of affected people who do not want to lose the economic and social cohesion of what they call “Yusufeli”. The issue is not simply to relocate the town of Yusufeli in some convenient site, although this is a major issue, but of doing resettlement in a way that preserves existing ties. The consultants need to consult affected people in what options they see and then ask the consulting engineers to design and cost various alternatives that may demonstrate their social and economic feasibility. 30. The present view of many affected people is that the authorities have decided on a number of sites13 within which Yusufeli must make a choice, while many residents and leaders wish, at a minimum, that other alternatives be investigated. It will be important for the consultants to be guided by DSI on whether other alternatives can, at this stage, be investigated since this will frame the debate and the reaction of affected people to the final RAP, regardless of what it contains. 31. The Consultants may also wish to investigate host communities about the availability of land and housing sites. In addition, the current Consultant should investigate the use of Treasury land in higher elevations next to affected areas for resettlement based on new agricultural models, including the use of pump irrigation, should transport not be a binding constraint in these areas. It should be possible to carry out these additional tasks within the existing contractual arrangements for the RAP preparation. 13 Sites which they identify are associated with the villages of Kilichaya, Ogden, Sarigul, Alanbasi, Cevreli, Ishani and Demirkent. 17 Institutional arrangements 32. The current TOR has insufficient institutional focus on implementation arrangements and their budget implications. Currently, a large number of public agencies, ranging from DSI, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the General Directorate of Rural Services, and many others, coordinated under the Provincial Governor, are involved in resettlement implementation. This situation, in the past, hindered the effective and timely delivery of the required infrastructure and other resettlement arrangements. There is therefore need to provide guidance concerning realistic institutional arrangements that would allow the implementation of a RAP. The coordinated approach of GAP should be examined as well as the process in the Turkish legislature of a proposal on institutional framework for resettlement, including a possible river basin approach. 18 ANNEX 1 Comments on Survey Instruments Prepared for the Resettlement Plan of Yusufeli Dam 1. The survey instruments submitted by Sahara Muhendislik to DSI have been reviewed. It is recommended that they be re-drafted and submitted to DSI for approval. As they now stand they are not appropriate for the specific context of Yusufeli. The consultants should carry out extensive field work prior to re-drafting the survey instruments. Once they are re-submitted and approved, they should be pre-tested. The analyses of the pretests together with the original instruments should be submitted to DSI for comments prior to the implementation of the surveys. 2. The draft research instruments submitted to DSI for approval by Sahara Muhendislik require substantial additional work to fit the specific realities of the resettlement context presented by the Yusufeli Dam. The drafts have been taken directly from the survey instruments used for Ilisu Dam. The Ilisu questionnaires themselves had a large number of problems resulting from inadequate field work and pre-testing. Replicating the Ilisu survey in Yusufeli will not only result in the replication of these problems but would also introduce a large number of new ones. Clearly, the drafts submitted for Yusufeli have not been prepared by a team that conducted sufficient field work in the area; nor is there any evidence that they have been pre-tested. 3. In the rest of this memo, a specific list of the issues relevant for the drafts submitted is provided. However, a new draft should not be based on these comments alone. Rather, extensive observations should be made in the affected area to prepare survey instruments appropriate for the resettlement context of Yusufeli. Equally important is collaborate with the regional director of DSI and other governmental organizations prior to finalizing the surveys so that their information needs are reflected in the surveys designed to address the specific problems to be addressed on the Yusufeli context. The suggestions of other stakeholders, including the town people, the villagers, local government officials and civil society organizations should likewise be reflected in the new draft to be pre-tested. The new drafted efforts should aim to address the specific problems of Yusufeli. The questions raised should be transparently relevant and useful for the preparation of a resettlement action plan as well as for the ability of DSI to estimate resettlement costs. 4. Some specific comments on the various research instruments submitted are provided below. Because the draft instruments do not meet the specific context of Yusufeli, comments on each individual question are not provided. This should not be interpreted to mean that individual questions excluded from the comments are appropriate. a. Focus groups: The type of focus group questions drafted are far too general to be useful for any planning process. Moreover, many meetings have already been held. The proposed exclusion of women from the focus groups is also not acceptable. Even if the consultants hold these meetings to re-draft their research instruments, the proposed questions are too narrow. If on the other hand, these are proposed to address specific 19 planning issues that emerge from the surveys to be conducted, they should be designed once these issues are identified. b. Household identification: It is unclear that the concept of “hane-reisi” is known or relevant for the people of the region. This should be established. There should also be a clear and agreed upon decision as to the person with whom interviews will be held. Interviews with people outside the household should not be carried out. Interviews with people under a certain age should likewise not be allowed. In the town, “hane no” instead of street and apartment number has also been proposed as a means of identification. This needs to be verified as appropriate. In the villages, house numbers have not been used for identification. Since DSI might send an independent team to verify that surveys have been carried out correctly, it is important that the consultants (i) clearly establish the procedures for identification of the affected households; and (ii) define and communicate to DSI the procedures that the consultants will use for quality assurance and verification purposes. c. Respondent and household characteristics: No systematic effort has been made in any of the draft instruments to characterize the respondents and the households. In addition to their gender, age, number of children and education, exposure to external labor markets, current work patterns, etc, all affect the information received. Similarly, household composition with respect to gender, age, human resources characteristics need to be established. The respondent characteristics in the drafts submitted appear to be based on the assumption that the “head of the household=a man” is the respondent. In reality an unmarried elder son or daughter might respond. Should this happen, a larger number of households would appear “childless”. In this context (q. 7), it is important to note that many people do not understand the concept of "hane". Therefore, alternative concepts should be tested and reported (e.g., “living in this house under one roof”, etc.). Also note that “since when you are living here” is not a clear question (q.8) as “here could be Yusufeli, the specific village or the specific house or even the province. Also, if q.8 is relevant, it should clearly be defined and the number of year of residence should be recorded numerically (such as 10,30,40, etc.,). As for q.9, it is unclear as to how the responses will be recorded if there are several school age children of various age and gender. Thus, for all household members (including those who work outside the community on a seasonal basis) age, gender, schooling, work and employment patterns, source of income, monthly income contributions—including in-kind) should be recorded. d. Matching respondents, households, communities, and project impacts. Eventually, the survey instruments will be analyzed within a number of interrelated contexts. Thus, the consultants should plan to set the individual responses in the context of their households, communities, and dam impacts. Needless to say this can be done after the surveys are carried out, but planning for them ahead of time will be useful. e. Assets. Assets are the most important elements of the resettlement planning within the Turkish context. Incomes, on the other hand, are at least equally important in the international context. However, the draft surveys do not adequately and 20 systematically cover the asset ownership issues. Since the problems are innumerable, several illustrations are provided. Imagine in q.10 that either an unmarried elder child, the wife of the primary bread winner or the wife of the “household head” (who could be an old male) were answering this question and they knew that the house title deed was registered in the name of the old man. This would result in a “no” answer when the household members actually own the house that one of them own. Imagine also a situation whereby (q.11) the house consists of multiple stories, and each story is owned (with or without a title deed) by one child who regardless of their marital status “eat from one kitchen”. Would the survey instrument register them as multiple households each with a separate “owned” house or one household with multiple homes? Each of these possibilities have very different resettlement entitlement implications. The questions dealing with the size and the type of the house are likewise inadequate. Most households are built with mixed building materials. Thus, q. 12 is not appropriate. All numerical questions, should be recorded numerically not in a pre-coded manner. Since every home has some sort of a kitchen and a toilet, etc., what one needs to establish is not merely their presence of absence but their quality. Thus, the survey should aim to identify housing quality indicators that are locally appropriate and try to guide the resettlement planning process by providing information that would allow DSI to estimate the expropriation costs. The establishment of titles is important. However, in many areas there is no cadastre and thus no title deeds. Thus, asking ownership questions premised on titles is misleading because it understates the assets as well as the cadastre problems faced. Home and asset ownership outside the communities is relatively widespread and relevant for resettlement planning. However, asset ownership outside villages is covered merely with one misleading question (q.13) that establishes asset ownership with title deed in a yes/no form without further details. Ownership of homes, garden, vineyards, cultivable land, livestock, presence of title deeds, the registration of these deeds for men, women, individual children, are all important. Using land size measurements appropriate for the area (as donum is not used in many parts of Yusufeli) is likewise important. Exact specification of tree and vineyard ownership, the type, age and productivity of each tree owned is crucial. A precise definition of the concept of “irrigated” land is likewise important as formal irrigation supplied by DSI does not exist, but there is extensive informal irrigation. The draft surveys for both the rural areas and the town is extremely inadequate for a clear identification of the assets. f. Incomes. Income restitution is likewise a critical issue, but inadequately covered in the surveys. Direct wage, salary incomes, in-kind incomes, remittances, agricultural incomes are not systematically covered. For instance, q.21 asks for annual income without specifying the year. It pre-codes the answers which will cause loss of information. It also does not specify the source of income. No family, regardless of how educated, can answer such a general question. The concept of “others’ work= baskalarinin isi” is not familiar to the people. Is this to mean agricultural work for other rural families? “Do you or others from your family work for others for wages? If so, how 21 much do they receive?” The answer will depend on how many work, in what capacities, when, where, etc., Instead, we would need to know, how many work for wages or salaries, each for how long or how many months of the year and when did they get paid last and how much did they get for that month or specified number of days. Key information concerning access to pastures, mezras, yaylas, etc., are also missing. g. Resettlement preferences. These questions too are more appropriate for Ilisu than for Yusufeli. Q.28 , Q.29 are repeated. Where people will go, what decisions they make depend on their current land ownership in “yayla”s and other mahalles (and these have not been established). These preferences also depend on the new transport network. Thus, the questions should aim to establish preferences in a concrete context. i. Transport infrastructure and marketing. The resettlement issue of Yusufeli centers around the transport network and other social/administrative/political connectivity factors of the 60 villages that define the county. These has been no attempt within the survey to capture the nature of the current interrelationships, why and how important they are in defining the quality of people’s lives. The establishment of people’s expectations with regard to the new network is similarly very important. j. The town of Yusufeli. This draft suffers from all of the above concerns. In addition, it is totally inappropriate to capture the income profile of the town where most people make a living from commercial activities. Multiple asset ownership is widespread, thus giving the town people ample opportunities to return to their original villages. In addition, rental house and especially shop occupancy is widespread and extremely relevant for resettlement. There is a need to fully re-design the Yusufeli town questionnaire. k. Headmen surveys. These contain a great deal of information already covered in the household surveys and are thus not functional. Secondly, they attempt to obtain some information of infrastructure without any attempt to define the extent and quality of the infrastructure. Also, they exclude crucial concerns relevant for the transport, marketing and communications network. Summary: The draft research instruments are not useful for resettlement planning purposes and are not relevant for the specific context of Yusufeli. There is a major risk that the information gathered through these instruments as presently defined will not produce an appropriate resettlement plan and, therefore, could result in an extremely negative reaction on the part of the affected people and their political representatives. In addition to the above comments, any redesign of the instruments needs to take account of the fact that the Yusufeli situation differs greatly from others in that: the most important impact of the dam reservoir on the largest number of people may well deal with the fact that the transport network, which is now 22 extensive and critical to the social and economic livelihood of the area, will be inundated for almost all affected people. The second most important impact of the dam reservoir appears to be the inundation of agricultural land that would need to be replaced using different agricultural technology, especially for those people who will retain their houses but not their land following dam construction. The destruction of housing, usually the most important aspect of resettlement, may be, in the case of Yusufeli, important, but not as important for the resettlement plan as a whole as the transport and agricultural aspects. Since a new town has to be created for the resettlement of the town of Yusufeli it would be essential to understand through a process of social assessment, stakeholder consultation and citizen participation what are the minimum requirements from government for the creation of a replacement town that would fulfill the economic and social functions of the present town. The draft research instruments need to be re-designed with these comments taken into account. 23 ANNEX II: Mission Notes Preface The consultant was asked to visit the Yusufeli Dam impact area by DSI and the consortium. The consultant wishes to express her appreciation to the regional director of DSI, Mr. Mehmet Kilinc, who hosted her and provided his staff to accompany her in the area. The consultant also wishes to thank the regional governor who met with her and presented his views on the challenges surrounding the Yusufeli Dam. The consultant was able to visit Yusufeli town on three separate occasions, to see the seven proposed resettlement sites14, and to have focus groups interviews in villages and hamlets that will be partially or fully affected by the Yusufeli reservoir and in the town of Yusufeli. The consultant also wishes to express her thanks to the mayor of Yusufeli, Mr. Yusuf Saglam, who accompanied her on several of her visits and who arranged a meeting and a luncheon attended by the local leaders of the six major political parties. Mission Impression – Overview The dam site and reservoir area represent a classic hydroelectric generation site: narrow valleys with high volumes of water descending rapidly between high mountains. The potential population of about 30,000 that would be affected partially or fully by the Yusufeli reservoir can be divided into four separate groups: 6-7,000 who live in the Ispir valley15 connected to Yusufeli town by a road system of about 55 km; 6-7,000 who live in the Barhal valley connected to Yusufeli by a road system of about 60 km; 6-7,000 who live in the Oltu/Tartum combination of valleys connected to Yusufeli by a road system of about 65 km; and 6-9,000 people who live in Yusufeli town which is the center connecting the three valley systems. In total there appear to be about 31,000 potentially affected people in the three valleys living in some 60 villages, often with hamlets and in Yusufeli town. The dispersed nature of the villages and hamlets may derive from the fact that agricultural land is largely in narrow strips along the river, although there are occasional broader areas to the southwest. 14 The sites are identified by the association with the following villages: Kilickaya, Ogdem, Sarigol, Alanbasi, Cevreli, Ishani and Demirkent. 15 There are, in fact, five separate valleys which will be inundated by the reservoir: one to the north towards Sarigol, one to the west towards Ispir, and three to the east which this report combines into one. 24 Transport An overpowering impression, reinforced by almost every discussion the consultant had, concerned the vital role that road transport plays in the social and economic life of the impact area. One of the three valley systems has no access to other areas other than through Yusufeli town; for the two other valley systems, Yusufeli town is the nearest commercial and administrative center. The roads, which have been constructed, often to paved standards, in all of these valley systems, near the river in most cases, will be flooded by the reservoir. If people remain in the impact area, replacing the transport network, either by road or by water, or by a combination, appears to be of the highest priority and of the greatest concern to the affected population. It will be a challenge for engineering consultants to provide road transport options built either on the mountain slopes or higher up so that people are able to remain in the impact area. Without access to road transport, resettlement within the impact area would be made impossible as would be the survival of some of the villages. Unit prices to calculate the overall cost of road transport should be readily available from the road network currently being constructed around Artvin in similar if not more demanding conditions. The Economy The people in the river valleys outside of Yusufeli town land derive their income largely from agriculture in the river valleys, often in narrow bands of built land next to the river that is irrigated, largely by gravity systems from upriver, although there is some pump irrigation. The land has often been built suggesting great innovation and dynamism on the part of the population. It is repeatedly said that much of the cultivated land is created by the people physically carrying soil from wherever they could obtain it. There is also livestock raising based on the use of highland pastures. The farm systems use intensive methods to cultivate fruits and vegetables with some cereal production. The fruit and vegetable production requires access to transport since much of it appears to be sold “as is” rather than processed. There is also some fish-farming and tourism, often based on weekend travel from neighboring cities. The economy of Yusufeli town needs to be studied more in-depth, but appears to be based on its role as an administrative and commercial center for the surrounding river valley populations. Without the transport network, it is not clear what Yusufeli would serve economically and therefore it would be greatly diminished, as its predecessor as county seat, Ogdem, was many years ago.16 The enormous social capital that Yusufeli has built up is described in the main report. Suffice it to say that the people and political leaders of Yusufeli feel that the value of their town has not been appreciated so far by the 16 It is ironic that Ogdem , the previous county seat, is proposed as one of the sites for the new Yusufeli since Ogdem lost its importance with the development of the road system and commercial marketing in the mid 20th century. Reached by a difficult road with great elevation, Ogdem, a beautiful and tranquil high altitude village, is a challenge to reach in the summer, and more so in the winter. Today the young have left Ogdem and most of its fields are untilled. Two people live in Ogdem year around, one of whom was mayor when it was still the county seat. Ogdem, as an alternative site for Yusufeli, appeals to the environmentalist and mountain spirits of all of us, but those engaged in modern agriculture and commerce which resulted, inter alia, from the introduction of the automobile, may feel that Ogdem is more appropriate for hiking and summer camping. 25 authorities, that their willingness to prepare their own feasibility study for a site in which they are interested has been ignored, and they believe their political, economic and human rights have not been respected. The RAP will have to deal with the reality of this situation which, in international experience, is best done through a genuine and transparent process of information/communications, consultation and participation. The importance of Yusufeli and the depth of feeling about its future should not obscure the fact that many of its citizens appear to have the skills and capital that might allow them to survive elsewhere. It is also true that some are inquiring about the possibility of establishing two county centers, not insisting that the unity of the center to be maintained. Yet others express very strong feelings and intend to take action should the road network not be replaced and social unity be broken. Even more important, however, is the concern with the future of the rural villages, which are not wealthy, that will be fully or partially inundated themselves and will be marginalized if a new transport network is not built. The resettlement and income restoration of these people is quantitatively the clear first priority. Housing Housing is often the first priority in a resettlement plan. There are indications that it is the third priority with regard to Yusufeli for two reasons: first, a fair number of housing in affected communities are built on the hillside and therefore will be spared, even when agriculture and transport are inundated; and second, the higher priority that affected people seem to put themselves, although this has to be verified through systematic surveys and focus groups, on transport and income generation, especially in agriculture. Even in Yusufeli, housing appears to be less of a concern than community preservation. The Yusufeli area does, however, contain a clear warning about resettlement and housing that is not connected to economic reality. Clearly visible from the road, on a barren hillside along one of the valleys, sits an apartment house constructed by government to resettle ten families whose homes had been destroyed in a fire. The apartment house looks attractive from a distance. Closer up, one sees that the area around the apartment house is largely barren, and the apartment house largely unused. Nine of the families never moved into this barren place, preferring to remain near their original homes; the one family that did move in is evidently far from self-sustaining. There appears to be substantial rental phenomena in the town center. Of the tenants many are shop owners. The restitution of their income will depend upon the availability of new rental opportunities in the resettlement site. This is an issue that needs to be more systematically studied in the socio-economic surveys and included (with associated costs) in the RAP. Public Services and Facilities While it was not possible to take a stock of the public sector services and facilities in the town and the villages, the town is particularly well equipped with them. To replace the health facilities, the schools, the office of the county governor, the municipal buildings, piped water system, the energy network, banks and other credit facilities, large 26 number of buildings that belong to various associations such as the association of traders will be a gigantic task that needs to start without any delay. To do so will not be easy and the people are not hopeful that it can be done. They note that everything else takes an enormously long time to do. In addition, many of the public agencies (with the exception of the Ministry of Education) may be short of funds to start or complete the work. Most important of all, none of the relevant cost calculations have been made. And the issue has not been included in the Terms of Reference RAP effort which has already been launched. Integrated River Basin Management for Resettlement The Coruh river basin is being developed in an integrated manner for dam development and the achievement of efficient hydroelectric power generation. The authorities may wish to consider whether resettlement, and non-hydro development possibilities, should also be seen in an integrated manner. Specifically with regard to resettlement, the different dam sites and their reservoirs will have similar resettlement challenges as well as site specific characteristics. However, viewing resettlement in an integrated manner would have a number of advantages: Resettlement costs can be spread across more than one dam investment leading to an evening out of costs and benefits; Specific resettlement options, such as the role of different transport modes, agricultural support mechanisms, job creation programs, resettlement sites in both urban and rural areas, can be viewed in both site specific and basin terms; Challenging issues, such as information/communications campaigns, participation and consultation strategies, etc. can be dealt with more effectively and efficiently, and with more commitment to their actual implementation; and The costs and benefits for unitary responsibility for resettlement planning and implementation may well be clarified.