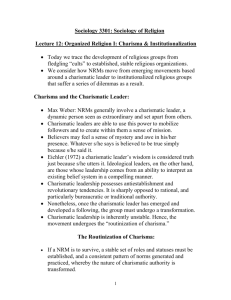

Sociology 3301: Sociology of Religion

advertisement

Sociology 3301: Sociology of Religion Lecture 12: Organized Religion I: Charisma and Institutionalization For any religious group to survive, they need to socialize young members, gain new members, and maintain commitment from existing members. Even then, however, this is not enough to ensure ongoing viability. They need to be effectively organized. In this vein, today we examine the development of religious groups from fledgling “cults” to established, stable religious organizations. Ever since Max Weber came up with the idea that most religions start out as cults led by a charismatic leader, much sociological work on religion has evolved around charisma. Yet, Weber noted that charisma is inherently unstable. Thus, if the group does not institutionalize, it will collapse shortly after the death of the leader. Many NRMs do not institutionalize and thus never develop into viable religions. Even when institutionalization is undertaken, this is itself a process fraught with many dilemmas, usually resulting in changes in the movement. Charisma and the Charismatic Leader: Weber maintained that new religions generally get their impetus from the attraction of a charismatic leader, a dynamic person perceived to be extraordinary and set apart from the rest of us. Sometimes this means that they are seen to be endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. These are often seen as inaccessible to the ordinary person, but regarded as of divine origin or exemplary, and on that basis the individual is treated as a leader. Charismatic leaders are able to use this power to mobilize followers and to create within them a sense of mission. Weber insisted that charismatic leadership is not to be judged as inherently good or evil, for it can be either. The point is that some people come to be regarded as exceptional, perhaps even divine by followers or disciples. While followers do not necessarily experience the mystical, they do become convinced that their charismatic leader is a direct agent of God, or perhaps even God incarnate. Believers may feel a sense of mystery and awe in his/her presence. For example, the feelings of Moonies for Rev. Moon saw him as the new Christ, God incarnate. Whatever he said is believed to be true simply because he said it. Similarly, whatever Jesus said is true for Christians because he is, in their eyes, God incarnate – a classic example of a charismatic leader who began a new movement. Later writers have distinguished between charismatic and ideological leaders. Eichler (1972) suggested that the charismatic leader’s wisdom is considered truth just because s/he utters it. The ideological leader, on the other hand, is one whose leadership comes from an ability to interpret an existing belief system in a compelling manner. Final authority rests outside this person, but s/he is still the primary interpreter (e.g. Chairman Mao). But in this section, we will use the term charismatic leader in the former sense. 1 One element of charismatic leadership that Weber thought especially important was its antiestablishment and revolutionary tendencies. He saw it as antithetical to social order because it was outside the realm of everyday routine in the profane sphere of existence. It is sharply opposed to rational, and particularly bureaucratic authority and to traditional authority. Unlike the focus of the others on rules for routine, everyday action, charismatic authority is irrational in the sense of being foreign to all rules. It repudiates the past and is, in this sense, a specifically revolutionary force. Weber was interested in the power of such leaders and their ideas to affect social change, and work in the latter 20th century focused on why people attribute such superhuman powers to others. It stressed that adherence to a charismatic leader and the development of a NRM is likely when certain social conditions prevail, and it occurs in stages by which the leader comes to be elevated to sacred status. Nonetheless, once the charismatic leader has emerged and developed a following, it is necessary for the group to undergo a transformation. Again, charismatic leadership is not only revolutionary, it is inherently unstable. Hence, the movement undergoes a process that Weber calls the “routinization of charisma.” The Routinization of Charisma: If a NRM is to survive over time, a stable set of roles and statuses must be established, and a consistent pattern of norms generated and practiced. Hence, the nature of charismatic authority is transformed. Charismatic authority on its own has a character specifically foreign to everyday routine structures, and must be radically transformed if the group is to last. The community gathered around a dynamic leader must evolve into one with a stable matrix of norms, roles, and statuses. This process of routinization is commonly called institutionalization. Any group that fails to institutionalize its collective life simply will not survive. Institutionalization serves both ideal and material interests of followers and leaders. The ideals of the group can be furthered only if it survives and only if it mobilizes its resources. Thus, it serves the ideological interests of adherents. Yet followers and leaders also have a material stake in the survival of the group. Insofar as they have invested time, energy, and resources into the group, they are likely to feel that they have a vested economic interest in its survival and success. Thus, the inherent forces working for routinization are strong. Maybe the most critical test is how the group handles succession. When the charismatic leader dies, the group may quickly disperse. Yet many people have a vested interest in its survival and will seek to ensure its viability. The problem is, who will provide the group with leadership? Equally contentious, how is that to be decided? Transfer of power to the next designated leader has important implications for group evolution. First, the charisma once identified with a personality must become associated with the religious ideology and the organization itself. The group, its body of 2 beliefs, and perhaps a written record (scripture) become sources of veneration. This more stable source of authority in itself changes the character of the group. Second, the decision making process itself becomes sacralized as the divinely appointed method of choosing the successor. This may involve designation of a successor by the original leader, some form of divinely sanctioned and controlled election, the drawing of lots, a hereditary succession, or something else. Regardless, followers must recognize the new leader(s) as the legitimate heirs or the group may be torn by schisms as splinter groups identify different people as the rightful leader (e.g. the Sunni/Shia split in Islam began this way). The new leader(s) is not likely to possess the same kind of unquestioned authority vested in the original charismatic leader. Some of the awe and respect will have been transferred to the teachings and to the continuing organization itself. The rules and values of the group must be attributed transcendent importance in and of themselves. Commitment is now to the organization and to the ideology of the movement, and the authority of the new leaders may be restrained by these stabilizing forces. No longer are the leader’s words taken as true simply because s/he said them. They must be evaluated in light of what the original leader said and did. In short, the new leader is usually an ideological leader rather than a charismatic one (e.g. Brigham Young, leader of the Mormons after the murder of founder Joseph Smith). Another issue involves the provision of a stable economic base. If some are to devote full time to the service of the leader/movement, then a continuing and consistent income must be secured. This can come from obligatory dues, from begging or soliciting, or from the establishment of some industry sponsored by the group. However done, securing a stable income is a critical part of the routinization process. Without this, there can be no full-time clergy, administrative staff, or other employees. Further, if there are no career opportunities within the organization, instrumental commitment may begin to wane. Indeed, such staff may be necessary if the group is growing and expects to continue expanding. Sometimes routinization is slow and takes time. After the crucifixion, for example, the disciples were discouraged and fearful but a series of subsequent experiences helped. Yet it wasn’t until the apostle Paul got into the act following a conversion experience that the faith was both universalized (from a small Jewish sect to a faith open to the gentiles), organized, and proselytized around the Mediterranean. It was he who forged links between congregations, collected money to support the parent organization in Jerusalem, met and travelled to cement a bond of loyalty to himself (despite protestations from Peter and James, who, apparently, were not good organizers). Paul established norms and expectations spelled out in his teachings and epistles. He often “corrected” local congregations when they followed norms emerging spontaneously out of their group. He assumed authority and was sought out as the person to resolve conflicts and define customs and mores. He also authorized teachers at various churches, even later bishops and deacons with supervisory functions. The routinization process was not complete by his death, but it was well under way. It was Paul’s organizational 3 initiative that eventually resulted in that powerful institution in European history: the Roman Catholic Church. Thus, in some cases a later organizer initiates institutionalization of the faith after the death of its charismatic founder. In other cases, the charismatic leader also happens to be an excellent organizer. Regardless, the routinizing function must be performed. Perhaps the most important test of this process is that of determining leadership succession. Yet, normalization of roles and statuses, establishment of norms, and provision of a stable economic base usually have to be addressed long before it becomes an issue. If this does not start earlier, the viability of the group for any sustained period afterward is unlikely. There have been thousands of NRMs that have been spawned but don’t survive. Thus, Heaven’s Gate, a California UFO cult, began to have problems when the more charismatic of its 2 leaders died. While it survived for a time under the surviving leader (who was felt to have communication with the other, deceased one), when he, too, became ill, members committed mass suicide to join them. While bizarre, there are many less dramatic examples of collapsed NRMs that failed to institutionalize. Indeed, the reason most people cannot name many groups that did not institutionalize is precisely because they failed to survive as a group. Many scholars believe that most, if not all, religions begin as charismatic cultic movements. Yet, if they are to survive, they must undergo the process of institutionalization. The extent of this will vary from group to group, but some must take place. Beyond this, institutionalization itself can create new problems or dilemmas. Dilemmas of Institutionalization: Religion needs most and suffers most from institutionalization. While necessary, it tends to change the character of the movement and to create certain dilemmas for the religious organization. O’Dea (1961) lists five of these. The dilemma of mixed motivation: When gathered around a charismatic leader, there is often single-minded devotion to him and his teachings. Followers are willing to make great sacrifices and willingly subordinate their needs and goals for the group. However, with the development of a stable institutional structure, desire to occupy the more creative, responsible, and prestigious positions can stimulate jealousies and personality conflicts. Concerns over positions and how secure they are can cause members to lose sight of the group’s primary goals. Mixed motivation occurs when such secondary concerns or motivations come to overshadow the original goals and teachings of the leader. While religious institutions do need to provide for the security and well-being of full-time professionals if they expect them to maintain high morale and commitment. To be satisfied in their work, they also need to feel that they can really use their creative 4 talents and abilities. The problem is that these secondary matters can take on primary importance for some members and subvert the original sense of mission. While this can occur when the charismatic leader is still alive (e.g. the disciples at the Last Supper), it more often occurs in later generations when members are more likely to belong to the group for reasons unrelated to the teachings of the charismatic leader. Mixed motivation may also involve a more subtle form of goal displacement. Thus, evangelical groups in Africa studied by Assimeng (1987) didn’t find their message so well received as their schools and hospitals. Eventually, due to these successes, some ended up spending much more time on these goals than the original one of converting locals to the faith. The original goals were displaced, while success and egos got tied up with these other motivations. The symbolic dilemma: Objectification vs. Alienation: For a community to worship together, a common set of symbols must be generated that meaningfully expresses the worldview of the group. Yet, this process of projecting subjective feeling onto objective artifacts and behaviors can proceed to the point that the symbols no longer have power for the members. They can become cut off from experience, from the inner dispositions of members, who become alienated from personal religiosity. For example, variant interpretations of a symbol in a given religious community – at least when vocalized – can clearly have divisive effects (e.g. the fish was like a secret code, a token or symbol that identified early Christians to each other when they were a highly persecuted group and fostered solidarity; today most people don’t know this and it has ceased to be a powerful symbol). In other cases, symbols may come to be seen by some as a barrier to communication with the transcendent. The anti-symbolism of the Puritans, who rejected stained glass and many Catholic practices as “idols” is one example. In their minds, visual symbols had come to symbolize an overbearing bureaucratic organization rather than a transcendent experience. Such alienation from established forms, symbols, and rituals can lead to either apathy towards religion or radical revolt and reformation of the faith. The development of objective, observable symbols that express a deeper subjective experience is part of the process of institutionalization. Symbols are necessary to bind a group together and remind them of a common faith, but it can also create problems. If the symbols lose their power and meaning for members, the group must either create new symbols or it will face internal problems of meaning and belonging. The Dilemma of Administrative Order: Elaboration of Policy vs. Flexibility: As a group grows and institutionalizes, it may develop national offices and a bureaucratic structure, along with a set of rational policies and regulations to govern the statuses and offices therein. This can create an unwieldy and overcomplicated structure, and ecclesiastical hierarchies are no less susceptible to red tape than other such bureaucracies. Moreover, attempts at reform may foster severe resistance by those whose status and security in the hierarchy are threatened. Mixed motivations can emerge with a vengeance. 5 While outsiders may see unwieldy organizational complexity and excessive rules as silly and unnecessary, people working therein often feel a profound need for guidelines to decision making. The search for concrete policy in the face of a new problem is common. If none is in place, people look to precedent in similar cases to formulate a new one. Beyond this, the development of elaborate and complex policy often results from the fact that people at lower levels feel uncomfortable making decisions without sanction from above. However, this felt need for clarity can mean that an organization is run entirely by rigid rules and regulations – a result that is uncomfortable, frustrating, and greatly reduces flexibility. Nevertheless, there will always be cases where either the rules don’t apply, or where to apply them strictly would result in a clear injustice. This dilemma goes around and around. Policy continues to be elaborated over time in such cases, but it may later restrict a group in its ability to be flexible with new circumstances. The Dilemma of Delimitation: Concrete Definition vs. Substitution of the Letter for the Spirit: In the process of routinization, religious messages get translated into specific guidelines of behavior for everyday life, concrete rules of ethical behavior. If not done, the belief system may remain at such an abstract level that the ordinary person does not grasp its meaning or importance for everyday living (e.g. Jesus’ teachings were illustrated in parables; the Old Testament covenant was spelled out in the specific ethical codes and religious laws set forth in the Torah). Nevertheless, in this process of translating the outlook of the faith into specific rules, something may be lost. Members may come to focus so intently on these rules that they may lose sight of the original spirit or outlook, and the religion can degenerate into legalistic formulas and judgmental behaviors inconsistent with the original intent of the founder (e.g. the legalism and ritualism of late Pharisaic Judaism; the fundamentalist, rule-bound interpretations of Islam by Salafists). When the letter becomes more important than the spirit, the original intent disappears. Hence the dilemma: abstract moods, motivations, and concepts must be made into concrete rules understandable for all, but these can later harden such that later generations become so literalistic and legalistic about them that they lose the central message altogether. The Dilemma of Power: Conversion vs. Coercion: If a religious group is to stay together and sustain its common faith, conformity to the values and norms of the group must be ensured to a large extent. Early on, the members are largely personal converts with a loyalty to a charismatic leader. Later generations, however, have grown up in a tradition and may not have had any personal experience so compelling that they unquestioningly accept the absolute authority of the group or the religious hierarchy and its interpretations in their lives. Indeed, some may seek to challenge these. In response, to maintain organizational integrity and consensus, religious organizations may resort to coercive methods of social control (e.g. charges of heresy, excommunication, the Inquisition, etc.) Regardless of the methods, maintenance of conformity through coercion rather than conversion is significant. Conformity due to internalization of norms is much more powerful, yet voluntary internalization by all is hard to sustain. Thus, institutionalized religious organizations may rely on coercion as a backup. Of course, in democratic 6 societies this is harder to get away with than in countries run by undemocratic, theocratic regimes. Institutional Dilemmas and Social Context: Yinger (1961) noted that O’Dea’s institutional dilemmas were not stated in terms of their social context. That is, he didn’t specify the conditions under which these dilemmas are most and least likely to occur. In fact, he saw them as inherent, unavoidable, and inevitable. Yet, there have been instances where some of these have not occurred, while groups have dealt fairly well with the others (Mathiesen, 1987). Thus, some social organizations and some social conditions may be more conducive than others to the occurrence of certain dilemmas. Mathiesen found, for example, that the symbolic dilemma is less likely to occur in groups that stress intense emotional conversion experiences and have strong mechanisms to sustain the plausibility of the worldview/symbol systems. Alienated or marginal social groups may also be less susceptible to this dilemma as religious symbols may serve to enhance group boundaries. Conflict with outsiders give symbols emotional force and relevancy for members. Similarly, the dilemma of delimitation may be less of a problem when the group sees itself as a persecuted or vulnerable minority group. Having a clearly defined set of fundamentals by which to measure faithfulness may become a sources of strength, even be defined as a virtue as these fit into the group’s concern with maintaining clear boundaries between themselves and the larger society. The dilemmas of mixed motivation and of power may also be lessened in circumstances where many commitment mechanisms are used. These heighten members’ commitment to the needs and interests of the group by causing them to identify self interests with group interests – lessening the likelihood of mixed motivations and reducing the need for coercion. These dilemmas of institutionalization often do plague organized religion, but they are by no means inevitable nor necessarily fatal. However, it does appear that these dilemmas are more pronounced when the organization is a majority religious movement rather than a minority protest movement preoccupied with tensions with the larger society. Once created, institutions may take on a life of their own and focus on their own survival more than anything else (e.g. coverups of clergy misconduct out of fear of how it would impact the organization). Thus, institutionalization is a mixed blessing. It is necessary for a NRM to turn into an established religious tradition after the death of a charismatic leader, but this carries with it many dilemmas – more specifically endemic to some religious groups than others. 7