CONCEPTUAL & EMPIRICAL ISSUES OF RTI

advertisement

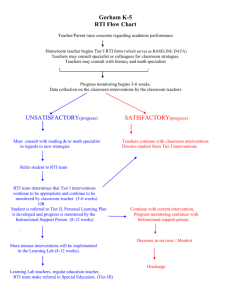

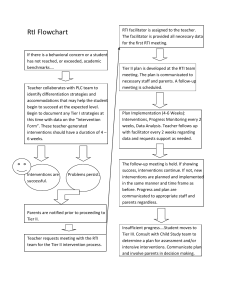

Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 1 Running head: CONCEPTUAL & EMPIRICAL ISSUES OF RTI Conceptual & Empirical Issues Related to Developing a Response-to-Intervention Framework John M. Hintze University of Massachusetts Correspondance regarding this article should be directed to John M. Hintze, Ph.D., University of Massachusetts at Amherst, School Psychology Program, 362 Hills House South, Amherst, MA, 01003 or email at <hintze@educ.umass.edu>. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 2 Abstract Response to Intervention (RTI) is used to promote the use of evidence-based instruction in classrooms with the goal to make general, remedial, and special education work together in a more integrated way. In doing so, RTI provides a means of identifying students at-risk for academic difficulties and specialized forms of education using assessment data that reflects students’ response to general education instruction and more targeted forms of intervention. This paper presents a conceptual overview of RTI and discusses key dimensions most salient to RTI development. Implementation issues and empirical research needs are discussed. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 3 Conceptual & Empirical Issues Related to Developing a Response-to-Intervention Framework At the present time, students with learning disabilities (LD) constitute the majority of the school-age individuals with disabilities, with the number of LD students increasing from 1.2 million in 1979-1980 to 2.9 million in 2003-2004 (U.S. Department of Education, 2004). As a result of these increasing prevalence rates, establishing acceptable criteria for LD identification has been a controversial issue in the field (Bradley, Danielson, & Hallahan, 2002). From a policy perspective as well, the identification of LD is a particularly salient issue in part because of the increase cost associated in providing special education to students served under this classification: $12,000 per student in special education versus $6,500 per student in general education (Chambers, Parrish, & Harr, 2002). Central to the identification controversy is the IQ-Achievement discrepancy. Although not required by law, a severe discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability is frequently used for identification, in spite of the numerous measurement and conceptual problems this approach presents (Fletcher et al., 2002; Kavale, 2002). For example, for students with reading difficulties, few cognitive or affective characteristics differentiate poor readers with discrepancies from those without discrepancies (Fletcher, Lyon, & Barnes, 1994; Foorman, Francis, Fletcher, & Lynn, 1996; Stuebing et al., 2002). The degree of discrepancy from IQ does not meaningfully relate to the severity of the LD (Stanovich & Siegel, 1994). Moreover, the discrepancy score has been demonstrated to be unreliable (Reynolds, 1984) and the preponderance of the evidence suggests that such an approach fails to inform instruction in important and meaningful ways (Elliott & Fuchs, 1997). Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 4 Dissatisfaction with the discrepancy approach to LD identification has been echoed by recent federal initiatives such as the President’s Commission on Excellence in Special Education and the Office of Special Education Programs Learning Disabilities Initiative. Each has called for a reconceptualization of LD from a within-child endogenous assessment of skills and weaknesses to a model which considers LD from the perspective of responsiveness to scientifically validated forms of instruction (Berninger & Abbott, 1994; Fuchs & Fuchs, 1998; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1987). Moreover, the recent reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004) contains authority that allows local education agencies to discontinue the use of IQ-Achievement discrepancy approach and to use RTI as part of the evaluation procedures for identifying students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) [PL 108446, Part B, Sec 614(b)(6)(b)]. As an alternative to the discrepancy approach to LD identification, RTI holds considerable promise and has the potential to (1) identify students with SLDs earlier and more reliably, (2) reduce the number of students who are referred inappropriately to special education, and (3) reduce the overidentification of minority students placed in special education (National Academy of Sciences – Donovan & Cross, 2002; National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities, 2005). Theoretical/Conceptual Rationale for RTI RTI is an approach to LD identification that was first proposed by a 1982 National Research Council report (Heller, Holtzman, & Messick, 1982), whereby three criteria were proposed for judging the validity of a special education classification. The first criterion was whether the quality of the general education program is such that adequate learning might be expected. The second consideration was whether the special education is of sufficient value to improve student outcomes and thereby justify the classification. Lastly, the third criterion was Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI whether the assessment process used for identification was accurate and meaningful. When all three criteria are met, a special education classification is deemed valid. The first two criteria emphasize instructional quality; first in the setting were the problem develops and second under the auspices of the special services the classification affords. By implication, the assessment process, referred to in the third criterion requires judgments about the quality of instructional environments and the student’s response to those environments. In 1995, Fuchs operationalized the Heller et al. (1982) framework (see also Fuchs & Fuchs, 1998) with the following assessment phases. In Tier I, the rate of growth for all students is documented. The purpose of this assessment is to determine whether the aggregate rate of responsiveness to the instructional environment or general education curriculum is sufficiently nurturing to expect student progress. If the mean rate of growth across students is low compared to other classes in the same building, in the same district, or in the nation, then the appropriate decision is to intervene at the aggregate level to develop a stronger or more beneficial instructional program. Regardless of whether the unit of analysis is classroom, grade level, school, district, state, or national comparisons, students at this aggregated level should be progressing at an appropriate rate without greater than expected numbers of students falling behind. Tier I assessment addresses Heller et al.’s first criterion that the quality of general education be such that adequate learning might be expected. After the presence of a generally effective general education curriculum has been established, Tier II assessment begins with the identification of individuals whose level of performance and rate of improvement are below the aggregate mean. Here the purpose of assessment is to identify a subset of students who may be at-risk for poor academic outcomes and possibly LDs as indicated by a lack of adequate responsiveness to the generally effective 5 Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 6 high quality general education curriculum. For this subset of students, standard protocol interventions are implemented that have been specifically chosen to supplement the general education curriculum and provide needed remediation in specified areas of academic skill development (e.g., phonological awareness, phonics, alphabetic principle, vocabulary, reading fluency, or reading comprehension). Student progress is routinely assessed and both level of performance and rate of improvement evaluated after a 6 to 8 week intervention period. Students who are responsive to Tier II intervention exit from the standard protocol intervention and returned to Tier I status (i.e., all instruction is delivered in general education). Students who fail to demonstrate change in level of performance or rate of improvement in Tier II are transitioned to Tier III where an individualized plan of remediation is developed and implemented with a small student:teacher ratio. The purpose of Tier III intervention and assessment is to determine if and with what types of intervention supports can the general education setting be transformed into a productive learning environment for students most at-risk for LDs. Student responsiveness to intervention efforts are monitored on a frequent (e.g., weekly) basis to examine changes in student performance level and rate of improvement. When corrective action fails to yield adequate growth does consideration of special education services to supplement general education become warranted? The assumption is that if such level of corrective adaptations in general education cannot produce growth for the individual, then the student has some intrinsic deficit (i.e., disability) making it difficult to derive benefit from the instructional environment that benefits the overwhelming majority of students (Fuchs & Vaughn, 2005). The conceptual framework for RTI and the RTI decision making process is illustrated in the Figures 1 and 2. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 7 Contemporary Issues Related to RTI Practices Since Fuchs (1995) operationalized Heller et al.’s (1982) framework, RTI as a model of instructional and assessment related service delivery has been redefined as a general education initiative with special education serving as a defining aspect of responsiveness to intervention. In particular, most contemporary conceptualizations of RTI contain the following essential components that require various levels of technical assistance to support implementation at the district level (NASDE, 2005): Overarching Principles We can effectively teach all children. RTI practices are founded on the assumption and belief that all children can learn. The corollary is that it is responsibility of the school system to identify the curricular, instructional and environmental conditions that enable learning. Once identified, systems must determine the means and systems to provide those resources. Intervene early. It is best to intervene early when learning problems are relatively small. Solving small problems is both more efficient and more successful than working with more intense and severe problems. Highly effective universal interventions in K-3 informed by sensitive continuous progress monitoring enjoy strong empirical support for their effectiveness with at-risk students. Use of a multi-tier model of service delivery. Use efficient, needs-driven, resource deployment systems to match instructional resources with student need. To achieve high rates of student success for all students, instruction in schools must be differentiated in both nature and intensity. To efficiently differentiate instruction for all students, tiered models of service delivery are used in RTI systems. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 8 Use research-based, scientifically validated interventions/instruction to the extent possible. NCLB and IDEA both require the use of scientifically-based curricula and interventions. The purpose of this requirement is to ensure that students are exposed to curriculum and teaching that has demonstrated effectiveness for the type of student and setting. Monitor student progress to inform instruction. The only method to determine if a student is improving is to measure the student’s progress. The use of assessments that can be collected frequently and that are sensitive to small changes in student behavior is recommended. Determining the effectiveness (or lack) of an intervention early is important to maximize the impact of that intervention with the student. Use data to make decisions. A data-based decision regarding student response to intervention is central to RTI progress. Decisions in RTI practice are based on professional judgment informed directly by student performance data. This principle requires both that ongoing data collection systems are in place and that resulting data are used to make informed instructional decisions. Use assessment for three different purposes. In RTI, three types of assessments are used: (a) screening applied to all children to identify those who are not making academic or behavioral progress at expected rates, (b) diagnostics to determine what children can and cannot do in important academic domains, and (c) progress monitoring to determine if academic or behavioral interventions are producing desired effects. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 9 Although most if not all users of RTI agree with the above overarching principles, various models vary on a number of key dimensions. Salient Dimensions in Implementing RTI Number & Purpose of Tiers. Most proponents of RTI adopt a multi-tiered model of intervention in which the intensity of services that are delivered is increased only after the child’s performance has shown to be to inadequate or under-responsive to intervention (Brown-Chidsey & Steege, 2005; NASDE, 2005; Reschly, Tilly, & Grimes, 1999). Such a multi-tiered framework is not new and has its origin in the prevention science literature. Although the number of tiers in the model vary, the focus of the tiers is typically on universal, selected, and indicated (or primary, secondary, and tertiary, respectively) interventions that are structured so that a student can progress through levels of intervention with progress monitored throughout the tiers (Kratochwill, Clements, & Kalymon, 2007). It is the movement through the tiers that provides the decision-making framework of the RTI approach. For example, in typical 3-tier approaches Tier 1 is characterized by a scientifically validated core curricula and universal screening. In Tier 2, targeted students who are lagging behind their peers on the universal screening measures are provided with either standardized or problem-solving designed interventions and response to such interventions is monitored weekly. Students who are under-responsive to Tier 2 interventions receive specialized forms of support in Tier 3 under the auspices of special education with individually developed instructional strategies tailored to the individual student’s needs. Comparatively, most 4-tier models again use scientifically validated core curricula and universal screening in Tier 1. Tier 2 again makes use of standard protocol treatments with frequent progress monitoring to Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 10 targeted students, however, individualized problem-solving is reserved until responsiveness to intervention that works for most students is assessed. If students are under-responsive to Tier 2, Tier 3 then involves more individualized problem-solving strategies that are typically more intensive as compared to Tier 2. Such intervention is often consistent with the types of interventions used in special education (and may indeed be delivered by a special education teacher), however, the working hypothesis is that the intervention is corrective, time limited, with the goal of having students progress back to Tier 2 and subsequently to Tier 1. Finally, for those students whose needs require sustained and long-term intensive and specialized forms of support, special education is provided under an individualized education plan. The difference in the two models lays primarily the manner in which intensive support is conceptualized with Tier 3 viewed as providing time-limited corrective support and Tier 4 being long-term continuous support. How At-Risk Students Are Identified. Although all models regardless of the number of tiers make provisions for identifying students who are at-risk in Tier 1 through universal screening, currently there is no agreed consensus regarding what these criteria should be (McMaster & Wagner, 2007). Using a relative normative approach, some approaches establish a percentile criterion whereby students performing below such percentile would be considered at-risk. For example, all students scoring below the 25th percentile may be considered at-risk (Fletcher, Francis, Morris, & Lyon, 2005; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2005). A potential problem with such a normative approach is that, by definition, there will always be students who fall in the lowest quartile and thus will always appear to be at-risk, regardless of their performance level (Torgesen, 2000). Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 11 Alternatively, absolute performance levels (e.g., benchmarks) can be used to determine risk status (e.g., Good, Simmons, & Kame’enui, 2001). For example, thirdgrade students who read fewer than 70 words correct per minute at the beginning of the school year may be considered to be at-risk. Benchmarks may be based on national or local data, and can be determined by using inferential statistics to calculate scores that predict later success, such as meeting end-of-year academic standards or passing state mandated tests (Hintze & Silberglitt, 2005; Silberglitt & Hintze, 2005). The Nature of Tier 2 Secondary Treatment. Once students are identified to be at-risk and move to Tier 2, interventions are implemented with the goal of remediating the area of concern and returning the student to Tier 1 status. Here, one of two approaches to interventions is commonly used: Problem-Solving Approaches and Standard-Protocol Approaches. Tracing back to the behavioral consultation model first described by Bergan (1977), problem-solving approaches attempt to address areas of concern by attending to and answering fundamental questions related to the areas of concern (Tilly, 2002): (a) What is the problem? (b) Why is the problem happening? (c) What should be done about it? (d) Did it work? In doing so, problems are defined as a discrepancy between current and desired levels of performance. For example, if a student is currently reading 40 words correct per minute and the desired level of performance is 80 words read correctly per minute, then there is a 50% discrepancy between what the child can currently do and the desired level of performance. Here, interventions are individualized to address areas of concern, delivered, and response to the problem-solving intervention is progress monitored using data-based decision making. Because of the individualized nature of the problem-solving approach each child who is found to be at-risk is handled differently, Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 12 although general classes of interventions may be used to address specific acquisition or skill deficits. Comparatively, standard-protocol approaches apply validated intervention approaches to areas of concern in a standardized fashion. As opposed to problem-solving approaches where each student’s skill deficit is considered individually, standardprotocol approaches apply interventions is a standard manner across students with similar areas of concern. Such approaches are often manualized or come with a protocol that is followed for all students, thus minimizing the individualized nature of the intervention as done with problem-solving. The operating principle with standard-protocol approaches is that students are experiencing difficulties not because of some underlying processing or idiosyncratic disorder, but because they have not been provided with adequate opportunities to learn (Clay, 1987). Standard-protocol approaches have demonstrated convincing empirical evidence that they can be used to effectively remediate academic difficulties in most, but not all, students (Gresham, 2007). The primary advantage of standard-protocol approach is that because of the manualized nature of the intervention, fidelity of implementation is more easily controlled thus providing better quality control of instruction. How “Response” is Determined. Although there is no single definition of what constitutes adequate response to intervention, most adopters of RTI utilize a combined approach that uses both idiographic (i.e., slope) and nomothetic (i.e., risk and/or final status) comparison features to determine “response” (Christ & Hintze, 2007). Such “dual discrepancy” approaches (cf. Fuchs & Fuchs, 1998) consider both learning rate and the level of performance as the primary sources of information used in ongoing decision- Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 13 making. Here, learning rate refers to a student’s growth in achievement competencies over time compared to prior levels of performance and peer growth rates. Comparatively, level of performance refers to a student’s relative standing on some dimension of achievement/performance compared to expected performance (either criterion- or normreferenced) (NASDE, 2005). In this sense, student response to intervention is a measure of student progress toward pre-established goal attainment (i.e., skill proficiency) and decreased risk (Callender, 2007). For example, if a low-performing student (as determined by relative risk-status) is learning at a rate similar to the growth rate of other students in the same classroom environment, he or she is demonstrating the capacity to profit from the educational environment and additional intervention is likely unwarranted. However, when a low-performing student is not manifesting growth in a situation where others are thriving, consideration of a special intervention is warranted. Alternative instructional methods must be tested to address the apparent mismatch between the student’s learning requirements and those represented in the conventional instructional program (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Speece, 2002; Fuchs, Mock, Morgan, & Young, 2003). Benefits & Empirical Questions That Still Need To Be Addressed The potential benefits of implementing an RTI model of identification and intervention are indeed numerous. First, using such a model for identifying students with potential learning problems has the highly desirable benefit of early identification and intervention. Screening students at-risk for learning difficulties as early as October of kindergarten decreases the likelihood of students slipping through the system with undetected learning problems. In addition, students can receive highly targeted and specific supports in academic areas of need. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 14 That being said, however, questions regarding the timing of screening assessments and the interaction of screening with the normal course of academic skill development are still unanswered. For example, screening at kindergarten may be less precise due to the rapidly changing skill development of students during this time of development. Will the interaction of timing of screening and academic skill development yield increased levels of false positives? Do students identified as at-risk who, over time and with no supplemental intervention, progress at adequate improvement rates? Are some students provided intervention unnecessarily, with supplemental instruction becoming expensive as it treats an inflated number of students? Do highly specified interventions provided early in the detection process decrease the likelihood that a student may develop a learning disability at some future point in time? Finally, what is the cost benefit associated with the RTI process? A second potential benefit of the RTI model of LD identification is the reduction in screening bias. By using systematic screening of all students, the reliance on teacher-based referral is decreased, thereby potentially reducing the bias and the variability of identification practices. The variability in teachers’ views and attributes associated with poor learning results in misidentification of students, with missed opportunities to serve students with true learning difficulties (Gresham, 2002). The reduction in screening bias through systematic school-wide screening represents a possible means for addressing issues related to disproportionate representation in special education. Still, however questions remain. If screening and progress monitoring data are to be used for identification, how should disability status be determined? What absolute differences in performance levels need to be evidenced for a student to be considered at-risk? Relatedly, what standards for rates of improvement should be used to indicate Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 15 that a student is or is not making adequate progress and responding or not responding to the intervention? A final potential benefit of RTI is linking identification assessment with instructional planning. The predominant discrepancy approach to LD identification commands substantial resources, with little connection between the resulting test scores and the design of effective intervention. Many general and special education teachers find results from typical IQ and achievement tests of little help in defining the appropriate educational program or designing instruction. Using RTI to identify students with LD shifts the assessment focus from endogenous student processing skills to the interaction of the learner with the educational and instructional environment. Conceptualizing LD in this manner opens the door to numerous manipulatible environmental variables that are rarely if ever considered with the discrepancy approach to LD identification. This shift in emphasis from assessment for identification to instructionally relevant assessment involves student progress monitoring and the systematic testing of instructional adaptations. While these procedures hold promise for informing instruction, numerous questions arise as to whether schools are adequately equipped with the knowledge and skills to affect such reform? Although one of the positive features of RTI rests on its logical appeal and a straightforward model of hypothesis testing, such an approach represents a paradigmatic shift in the manner in which students with learning difficulties and disabilities have been considered for the last 30 years. Whereby the discrepancy approach relies on the technical skills of a handful of school staff, RTI commits the use of an entire school staff to make decisions. Scaling the process up in such a manner requires the careful consideration of knowledge, skills, and resources from multiple school staff at multiple levels including the LEA level (e.g., mission plan, commitment to ongoing professional development, etc.), the school Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 16 building level (e.g., school improvement plans, accountability systems, delegation of responsibilities, administrators’ values, release time, etc.), and the student level (e.g., appropriate assessments are used, use of progress monitoring data, instructional plans are developed and implemented, etc.). Conclusions Recent legislation and policy initiatives have called for empirical challenges to current notions of educational services delivery and the manner in which we identify students in need of special educational services. RTI holds great promise in serving as a catalyst for further efforts – from both practice and scientific perspectives – in examining the way in which we provide assessment and intervention in schools. RTI models have considerable promise for screening, intervention services delivery, and system change. That being said, however, continued research is warranted to operationalize procedures and judgments, and evaluate the decision-making utility of the models in practice. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 17 References Bergan, J. (1977). Behavioral consultation. Columbus, OH: Merrill. Berninger. V. W., & Abbott, R. D. (1994). Redefining learning disabilities: Moving beyond aptitude-achievement discrepancies to failure to respond to validated treatment protocol. In G. R. Lyon (Ed.), Frames of reference for the assessment of learning disabilities: New views on measurement (pp. 163-183). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. Bradley, R., Danielson, L., & Hallahan, D. P. (2002). Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice. Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum. Brown-Chidsey, R., & Steege, M. W. (2005). Response to intervention: Principles and strategies for effective practice. New York: Guilford Press. Callender, W. A. (2007). The Idaho results-based model: Implementing response to intervention statewide. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.). Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 331-342). New York: Springer. Chambers, J. G. Parrish, T., & Harr, J. J. (March, 2002). What are we spending on special education services in the United States, 1999-2000? Advance Report, #1, Special Education Expenditure Project (SEEP), American Institute for Research. Christ, T. J., & Hintze, J. M. (2007). Psychometric considerations when evaluating response to intervention. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.). Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 93-105). New York: Springer. Clay, M. (1987). Learning to be learning disabled. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 22, 155-173. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 18 Donovan, M. S., & Cross, C. T. (2002). Minority students in special and gifted educaton. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Elliott, S. N., & Fuchs, L. S. (1997). The utility of curriculum-based measurement and performance assessment as alternatives to traditional intelligence and achievement tests. School Psychology Review, 26, 224-233. Fletcher, J. M., Francis, D. J., Morris, R. D., & Lyon, G. R. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of learning disabilities in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 506-522. Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., & Barnes, M. (2002). Classification of learning disabilities: A evidenced-based evaluation. In R. Bradley, L. Danielson, & D. P. Hallahan (Eds.), Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice (pp. 185-250). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Fletcher, J. M., Shaywitz, S. E., Shankweiler, D. P., Katz, L.,Liberman, I. Y., Fowler et al. (1994). Cognitive profiles of reading disability: Comparisons of discrepancy and low achievement definitions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 1-18. Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J., Fletcher, J. M., & Lynn, A. (1996). Relation of phonological and orthographic processing to early reading: Comparing two approaches to regression-based, reading-level-match designs. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 619-652. Fuchs, L. S. (1995). Curriculum-based measurement and eligibility decision making: An emphasis on treatment validity and growth. Paper presented at the Workshop on Alternatives to IQ Testing. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (1998). Treatment validity: A unifying concept for reconceptualizing the identification of learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 13, Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 19 204-219. Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2005). Responsiveness-to-intervention: A blueprint for practitioners, policymakers, and parents. Teaching Exceptional Children, 38, 57-61. Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., & Speece, D. L. (2002). Treatment validity as a unifying construct for identifying learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 25, 33-45. Fuchs, D., Mock, D., Morgan, P. L., & Young, C. L. (2003). Responsiveness-to-intervention: Definitions, evidence, and implications for the learning disabilities construct. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 18, 157-171. Fuchs, L. S., & Vaughn, S. R. (2005). Response-to-intervention as a framework for the identification of learning disabilities. Trainers Forum, 12-19. Good, R. H. III, Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2001). The importance of decision making utility of a continuum of fluency-based indicators of foundational reading skills for third grade high stakes outcomes. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5, 257-288. Gresham, F. M. (2002). Responsiveness to intervention: An alternative approach to identification of learning disabilities. In R. Bradley, L. Danielson, & D. P. Hallahan (Eds.), Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice (pp. 467-519). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Gresham, F. M. (2007). Evolution of the response-to-intervention concept: Empirical foundations and recent developments. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.). Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 10-24). New York: Springer. Heller, K. A., Holtzman, W. H., & Messick, S. (Eds.). (1982). Placing children in special education: A strategy for equity. Wasington, DC: National Academy Press. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 20 Hintze, J. M., & Silberglitt, B. (2005). A Longitudinal Examination of the Diagnostic Accuracy and Predictive Validity of R-CBM and High-Stakes Testing. School Psychology Review, 34, 372-386. Kavale, K. A. (2002). Discrepancy models in the identification of learning disability. In R. Bradley, L. Danielson, & D. P. Hallahan (Eds.), Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice (pp. 369-426). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Kratochwill, T. R., Clements, M. A., & Kalymon, K. M. (2007). Response to intervention: Conceptual and methodological issues in implementation. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.). Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 25-52). New York: Springer. McMaster, K. L., & Wagner, D. (2007). Monitoring response to general education instruction. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.). Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention (pp. 223-233). New York: Springer. National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDE). (2005). Response to intervention: Policy considerations and implementation. NASDE: Alexandria, VA. National Joint Council on Learning Disabilities. (2005). Responsiveness to intervention and learning disabilities. http://www.ldonline.org. Retrieved on October 29, 2007. Reschly, D. J., Tilly, W. D., & Grimes, J. (Eds.). (1999). Special education in transition: Functional assessment and noncategorical programming. Longmont, CO: Sopris West. Reynolds, C. R. (1984). Critical measurement issues in learning disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 18, 451-476. Silberglitt, B., & Hintze, J. M. (2005). Formative assessment using CBM-R cut scores to track Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI 21 progress toward success on state-mandated achievement tests: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 23, 304-325. Stanovich, K. E., & Siegel, L. S. (1994). Phenotypic performance profiles of children with reading disabilities: A regression-based test of the phonological-core variable difference model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 24-53. Stuebing, K. K., Fletcher, J. M., LeDoux, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz, B. A. (2002). Validity of discrepancy classifications of reading difficulities: A meta-analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 39, 469-518. Tilly, W. D. (2002). Best practices in school psychology as a problem-solving enterprise. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology-IV (pp. 21-36). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Torgesen, J. K. (2000). Individual differences in response to early interventions in reading: The lingering problem of treatment resisters. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 15, 55-64. U.S. Department of Education (2004). U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, Data Analysis System, 2004 IDEA Part B Child Count. Vellutino, F. R., & Scanlon, D. M. (1987). Phonological coding, phonological awareness, and reading ability: Evidence from a longitudinal and experimental study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 321-363. Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI Figure 1. RTI Conceptual Framework Core Instructional Interventions All Students Preventative, Proactive ~5% ~15% ~ 80% of Students Intensive, Individualized Interventions Individual Students High Intensity Of Longer Duration Targeted Group Interventions Some Students (at-risk) High Efficiency Rapid Response 22 Conceptual & Empirical Issues of RTI Figure 2. RTI Decision Making Framework. TIER 1: Primary Prevention - General education setting - Research-based instruction - Screening to identify students suspected to be at risk - Brief Progress Monitoring to (dis)confirm risk status AT RISK TIER 2: Secondary Prevention - Validated standard protocol or research based intervention - Progress Monitoring to assess responsiveness TIER 3: Tertiary Prevention - Intensified individually designed remedial interventions - Possible eligibility classification - Continuous progress monitoring - Progress monitoring to formulate IEP goals - Progress monitoring to assess responsiveness Responsive Unresponsive Responsive Unresponsive 23