“For the land is Mine”:

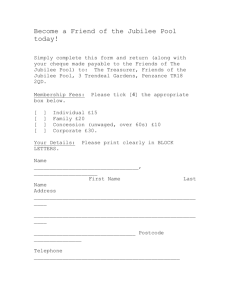

advertisement