What support will the UK provide? - Department for International

DFID Support to the ODI Fellowship Scheme 2012-15

Intervention Summary

What support will the UK provide?

The UK Government, through the Department for International Development (DFID), will provide a 3 year Accountable Grant (AG) to the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) to support its Fellowship Scheme over the 3 financial years 2012/13-2014/15.

The funding will be of up to £11,011,200 total, expected to be drawn down across the three successive FYs by £3,243,300; £3,760,800 and £4,007,100.

This support from DFID aims to ensure the Fellowship Scheme (FS) continues to provide excellent technical support to at least 20 developing country governments through the recruitment and posting of 50 early-career economists each year to work in civil servant positions for 2-year postings.

The Fellowship Scheme is a partnership between the employing government overseas (who contributed a total of 21% of the funding of the FS in 2011), ODI and donors/ other agencies.

DFID remains the largest funder of the Fellowship Scheme. In 2011/12, DFID provided 72% of the total FS funding

– 55% from the core grant and 17% from DFID country offices. This new core grant for 2012-15 consolidates nearly all of DFID’s support into the central grant, reducing the transactions costs to DFID and to ODI of discussing and administering multiple country-level grants.

The UK Government 1 has supported the ODI Fellowship Scheme almost since it began in the

1960s. In setting the funding level under this AG, DFID has taken into account the level of economist placements currently managed well by the ODI, the funding that other donors are expected to provide over the next 3 years, and the continuing attention to containing costs and ensuring value for money in the management and recruitment, placements, and in-post support to employed economists.

Why is UK support required?

Sound economic management contributes to growth and to poverty reduction. Trained economists can contribute by identifying and helping to assess various policy options and implementation steps, particularly in core economic management. Developing country governments need to own and direct their own policy development for effective and sustainable development, but often lack enough trained staff to handle the demands upon their ministries. Policy development and implementation may be less effective, or slower, as a result. Development partners can help to overcome the staffing constraint through paying for

1 DFID and its predecessors ODA and ODM.

or directly providing trained staff. The ODI Fellowship Scheme is one well-established and highly-regarded way of providing trained economists to developing country governments facing such constraints.

The ODI FS has been in operation since 1963. It has developed and evolved over the decades, growing to a steady state now of 50 new recruits each year, 100 economists in post at any point in time in developing country governments. It has been reviewed and evaluated every three years, and has consistently been found to deliver effectively the technical support that governments are seeking, and career-changing experience for professional economists wanting to work in international development.

What are the expected results?

This Accountable Grant will support work in at least 35 ministries in a total of at least 20 developing countries, to support stronger economic management so as to enable growth and service provision that reduces poverty. African states are the largest employers of ODI

Fellows, expected to employ at least 35 of the 50 new ODI Fellows recruited each year. Lowincome and conflict-affected states face particular staffing constraints and are priorities for the

ODI FS. Progress on the MDGs 2 has been slower in Africa overall than other regions, and mass poverty remains common in much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Sound economic governance includes low and stable inflation; taxation that is modest, predictable and progressive (taxing poorer people less than wealthier people); and effective public spending that provides the basic public services on which poor people rely more than richer people. Poorer men and women of the countries employing ODI Fellows will benefit indirectly from the Fellowship Scheme to the extent that Fellows contribute to better economic management which delivers the advantages above.

Sound economic management is also part of the foundation for private sector investment and growth, generating jobs and demand for other productive inputs and supply of goods that together drive economic growth.

Key changes that are expected to result from DFID ’s support include :

Employing governments in up to 25 developing countries report that the Fellows they have employed have been effective at providing direct technical assistance as well as contributing to colleagues’ capacity

Each year 2012-15, up to 45 Fellows majorly funded by DFID will be posted to up to 25 developing countries per year, for 2-year postings

At least 90% of ODI Fellows majorly funded by DFID are employed in low income and high poverty states

At least 30 early-career economists gain country experience and seek further work in international development

2 Millennium Development Goals

Business Case

Strategic Case

A. Context and need for a DFID intervention

1. Why support technical assistance in economic management? a. Economic management matters for poverty reduction

Growth is necessary for poverty reduction (see Ravallion 3 , Kraay 4 ) and progress towards the non-income focussed Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in Low

Income Countries (LICs) is dependent on growth (see Bourguignon and others 5 ).

Ministries of Finance, Planning and Central Banks are the central institutions responsible for such broad-reaching areas of work as setting and implementing policies and procedures on taxation and public expenditure, public debt and its financing, the macro management of aid and other capital flows, domestic currency management, exchange policy and reserve management, and national accounting and other economic statistics. Economic policy in areas such as trade, industry, competition and regional integration also matter for growth and are often led by separate ministries and departments.

Poverty reduction requires broad-based economic growth that generates jobs and raises incomes; access to essential services such as water, infrastructure, health and education; and protection from shocks that erode assets or earning capacity and push households into poverty.

Sound economic management has a part to play in achieving each of these elements. b. Technical assistance can improve economic management

Developing countries often lack institutional and technical capacity across a range of areas of governance, including economic management. This is both a cause and an effect of their constrained economic development. The assessment that local institutional and technical capacity is often insufficient for the challenges that developing country governments face is documented in much of the grey literature around development programmes and their effectiveness.

Technical assistance is part of the development community’s response to this perceived capacity gap. Labour markets for technical professionals such as economists are often thin and distorted in developing countries, particularly in smaller

African states – there are relatively few economics graduates each year, and public sector pay of ten can’t compete with private or international pay rates. Syllabuses from local universities might lag some years behind those abroad. Recruiting and retaining

3 Ravallion, M. (2001). "Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Looking Beyond Averages," World Development, 29(11), 1803-

1815.

4 Kraay (2006).“ When is growth pro-poor? Evidence from a panel of countries ,” Journal of Development Economics,

80(1), 198-227.

5 Bourguignon and others (2008).“Millennium Development Goals at Midpoint: where do we stand and where do we need to go?”Background paper for European Development Report 2009.

high-quality economics graduates for the public sector is often a struggle.

2. Effective technical assistance is controlled and managed by the receiving ministry

Technical assistance takes many forms, of which direct provision of resident technical advisers in ministries is a frequent one. This reflects that many issues ministries need to work on are complex and take time to work through, and embedding changes to policies and practice takes time. Efforts to improve aid effectiveness over the last 15 years have stressed the need for TA to be adequately controlled by the receiving government – who should be articulating demand for the technical support; specifying the jobs to be done; selecting the technical advisers to fill posts.

The evidence on the development impact of technical assistance is limited. TA is often provided alongside other financial, material or advisory interaction or support, so it is hard to separate out how much of the changes that may be observed is due to which element of support. Establishing the counterfactual (what would have happened without the TA) is very difficult, requiring a lot of detailed and complex information about the inner workings of the organisation in question, which is rarely feasible to collect.

A DFID evaluation in 2006 -

‘Developing Capacity? An Evaluation of DFID-funded technical cooperation support to economic management in SubSaharan Africa’ (Ev667) sought to understand the contribution of technical cooperation to the development of organisational capacity for economic management

– that is the ability of the key organisations (Ministries, Departments) involved in the economic management process to discharge their functions. It studied projects in Malawi, Zambia and South Africa concerned with economic management. It found that “Long-term technical cooperation has been most effectively provided where the provider is of a high technical calibre and is seen by the organisation being supported as responsive to its needs and as under its direct management control. …. Cases where outputs have not been achieved have been characterised by: Technical weaknesses or lack of appropriate (particularly interpersonal) skills among the TC providers; a perception from the organisation supported that it had insufficient effective control over the providers; insufficient attention to ... the capacity to use short-term support effectively; lack of effective government commitment to the reforms supported

.”

The evaluation concluded that “TC can be highly effective in a range of contexts

(including ones where the institutional setting for capacity development is poor

– indeed it may be of most value in achieving transactional impact in such conditions) but this effectiveness is not necessarily related to capacity development. Technical cooperation is not fundamentally what builds organisational capacity, since high levels of organisational effectiveness are in general needed for technical skills to be absorbed and used within an organisation.”

Anecdotally, the strong demand that continues to be expressed by government ministries in developing countries for technical advisers to work for and with them, suggests that the responsible officials believe there is more gained than lost by bringing in TA.

3. Why support the ODI Fellowship Scheme? a. The ODI FS is an effective source of economics TA

The ODI is a leading development research organisation with a global reputation for high-quality, policy-relevant research and analysis. DFID and ODI have a strategic partnership on analysis and research on reducing poverty in developing countries.

The FS belongs to the ODI and both benefits from the strong reputation that the ODI has for development policy analysis more generally, and contributes to ODI’s reputation through the high quality of the Fellows it has consistently been able to recruit over the past 49 years.

ODI does not provide large-scale support to institutional reform of government ministries in developing countries. Sometimes, Fellows are posted into a reform agency or a reforming ministry, as part of a wider donor-supported effort. Often, they are posted to quite mature and stable ministries, which ODI assesses are both in need of junior technical support and able to use it well.

The FS is likely to be having transactional impacts, and contributing to transformational ones (where ambitious wider efforts do move ahead and become real in part because the technical capacity existed to help deliver it).

The ODI Fellowship Scheme corresponds quite well with the evaluation findings on effective Technical Cooperation. Ownership and control of the TA provider (staff member) is a central element of the FS

– Fellows are employed by the host ministry and work alongside other civil servants of that country. The FS management team select the best early-career, trained economists from the hundreds who apply each year (the ratio is currently about 600 applications for 50 places) and offer several candidates to each employing ministry to select from. The employing ministry provides the normal pay, working conditions and leave as for other civil servants at the grade; this investment from often very constrained staffing budgets demonstrates their commitment to employing the Fellow. The TA is sustained and predictable, with two year postings, and ODI often being willing to place a follow-on Fellow if the need continues and if conditions are appropriate.

The FS management team assesses ministries on their need for an economist, and their likelihood of being able to make good use of a junior economist’s efforts. The assessment is informed by views from partners in country (current employers of

Fellows elsewhere in government; development partners including DFID), often formed over several visits and exchanges with the ministry over time; tested with practical requirements of a job description and local employment terms and conditions being provided by the would-be employer. While far from being a holistic institutional assessment, the FS has a high success rate in placing Fellows where they will be able to contribute effectively. The FS has a very strong track record of satisfied employers, satisfied Fellows and repeat requests from governments to continue to provide them with support.

The FS has been much copied by other technical assistance schemes, though none have the particular focus on economic management that the FS has. This specialisation al lows the ‘offer’ to employing governments and to Fellows to be clear, the recruitment and placement efforts to be well-defined and efficient.

The review of the FS over 2009/10-2011/12 (see Annex A) concluded in Jan 2012 that: a) The FS cost-effectively recruits and places high-calibre trained economists in useful posts; b) The OD IFS management team is delivering an efficient service through 100 placements (50 per year for 2 years each) with target ministries across 24 countries; c) The impact of the FS is very good in ter4ms of gap-filling for key economist posts in ministries. Its impact in sustainable capacity building is more mixed.

The review concluded that DFID should continue to support the FS with core funding.

It made a number of recommendations for further strengthening the FS, viz: i) DFID core funded posts in low-income countries have been and should continue to be a priority for the ODI Fellowship Scheme; ii) The number of Fellows in post each year (50) has been achieved but should be considered as a ceiling of posts per year, not a target; iii) The review found the efficiency of DFID funding is likely to be highest through a central funding mechanism; iv) There is a recognised demand for and duty of care justification for ODI to provide more resources to support Fellows inpost (‘pastoral care’); v) There are no substantive issues with the efficacy and impact of the scheme in terms of its gap filling function in ministries; vi) The Fellowship Scheme should develop user-friendly tools and provide effective training of Fellows on capacity building, while being realistic about what can be achieved in different contexts; vii) Further consolidation into fewer countries is consistent with continuing attention to the quality of posts and seeking to strengthen the pastoral care of Fellows; viii) The briefing session should in future include: a. Security training covering guidance on reducing, managing or avoiding the security risks and clear emergency response rules; b. Capacity building guidance and training materials – learning lessons from previous ODI Fellows on what is achievable, what works, and building on

ODI’s considerable knowledge in this area. ix) The capacity building role should be specified in the Scheme description, the

ODI web site, Ministry briefings, job descriptions for Fellows and through a formal healthcheck as part of the ODI’s pastoral care during its country visit programme; and

x) A number of suggestions to improve the matching/placement process, on

Objective setting and monitoring progress of Fellows after 4

–6 months in post.

These recommendations have been almost entirely accepted by the ODI FS management team and are reflected in the plans for the next 3 years of operation, including more staff time for pastoral services; funding for security training; renewed focus on capacity building in practical and achievable ways by Fellows; and the higher core funding to take on more

DFID-supported placements centrally rather than through country-level grant arrangements.

The recommendation not wholly accepted by ODI is vii) above, where the ODI has agreed to a ceiling of DFID-funded posts of 40 new placements per year, but ODI retaining its right to arrange other posts that are funded by employing governments or other development partners. a) Many Fellows continue to work in development, having gained valuable experience working alongside colleagues in ministries

The ODI FS has a high rate of successfully completed 2-year Fellowships – 92%, with early exists mostly being due to post-Fellowship work offers. The review cited above found over two-thirds of Fellows go on to work in international development.

Of people who were Fellows over 2008-10 and 2009-11, 72% continued in international development (11% with DFID, 17% continuing to work in the ministry of their Fellowship, 45% in other development programmes and agencies); 11% went on to do further academic research (eg PhDs), many of which would also focus on economic development. The strong feedback from former and current

Fellows interviewed is that their Fellowship has strengthened their passion for working in development and increased their ability to understand the problems that countries face and how best to work to overcome them. b) Most partner governments cannot easily afford the full costs of Fellows

ODI Fellows are a very small part of the total technical assistance provided to the governments of developing countries. Most TA is relatively short term (weeks or months of input) and focused on a specific project or process of change. Only occasionally is this fully funded by the recipient government; even where the TA is contracted and controlled by that government, the funding usually comes from external development partners, reflecting that developing countries lack finance as well as skilled human resources.

ODI Fellows sometimes substitute for more expert/ experienced and thus more expensive consultants; sometimes they help to amplify the benefits from more expert TA by adding to the ministry’s capacity to act upon and embed the advice that they receive.

It is common for much TA to be provided with office space and colleagues to work with; the FS goes further and requires the employing ministry to pay the local terms and conditions for each post.

This is consistent with the core idea of there being a gap in the staffing complement of a ministry, that due to the shortage of local skilled economists in country they have not recruited into, but that the post

is provided for in the dep artment’s administrative budget. The extra elements of providing an international Fellow – the transport cost for them to get to/from the posting; accommodation; a salary supplement that is attractive to young professionals who’ve invested in doing Masters level economics courses; pastoral care and insurance cover – are beyond the local salary provided for and these are met by the FS budget supported by DFID and other funding partners.

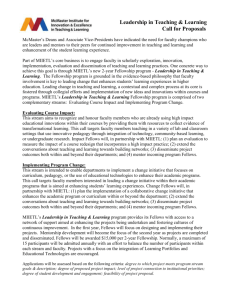

B. Impact and Outcome that we expect to achieve

Theory of Change for the ODI Fellowship Scheme

Country with high poverty has skill/staffing constraints on economic management

Ministry aware of ODI FS and asks for a Fellow

FS team assesses Ministry/ specific job offered as suitable for a Fellow

Fellow provided and works as junior economist providing

Higher capacity for economic analysis analysis and admin skills

Better understanding of policy options and relative each merits of

Stronger capacity to implement policy or process decisions

Better economic management in the country

Poverty reduced

Th e results chain from a Fellow’s work in a government to poverty being reduced in that country is obviously long and hard to measure. The strong demand for Fellows in more than

20 countries and through time does suggest that Fellows tend to add value to the teams and ministries they work in. Employers’ enthusiasm and endorsement of the FS was strong in the review of the last 3 years’ operations: employers tend to emphasise the immediate gap-filling and direct impact of having another capable member of their team to get technical and skilled things done; they ask less of Fellows in terms of training colleagues or building capacity other than through the demonstration effect of how they deliver their own work.

Nevertheless, the review concluded that there was scope to achieve modest but more sustainable capacity-building impact through raising the profile of this aspect of the FS with employers and Fellows and providing more examples and shared ideas for how to go about this. The new phase of FS funding will attempt more of this and see if it does improve the already-strong FS impact even further.

**The logframe for this support to the FS is being finalised *** Key results are above in summary

Appraisal Case

A. What are the feasible options that address the need set out in the Strategic case?

Having found the FS to be effective, and given the continuing demand from employing ministries for Fellows, DFID wishes to continue to provide funding to the FS. The recent scale of 50 new Fellows each year seems manageable in terms of there being at least that many appropriate posts asking for a Fellow in high-poverty countries, and at least that many high-calibre candidates that the FS manages to attract and secure for the FS. 50 per year also seems manageable with the scale of management input that the FS has had, although to address the stronger pastoral support that we have encouraged the ODI to adopt, a slight staffing increase is merited.

We assume therefore that the scale of the FS remains as now, with a continuing focus on low-income and fragile countries. The country mix matters for funding: the more fragile and conflict-affected the country is, typically the higher are rents and security provision (and even transport costs). The total cost to ODI of placing a Fellow range from about £10,000 a year to a post in a middleincome country like Namibia, to perhaps £30,000 a year to South

Sudan. This new phase of funding calls on the ODI FS to use DFID’s funding primarily on placements in low-income and fragile developing countries, as it is likely that the contribution of Fellows to very under-resourced ministries in those settings will be far higher than the same Fellows posted to a better-resourced institution in a less needy country.

We assess here three options for how DFID provides support to the ODI FS:

1. Fund FS only through a centrally managed Accountable Grant.

2. Support only individual FS postings in specific DFID bilateral support countries.

3. Central funding with the option of some DFID funding

Against the counterfactual of not providing DFID funding to the ODI FS.

The counterfactual – DFID does not fund the FS

The FS belongs to the ODI and its partnership model of funding is flexible to receiving support for the non-employer costs from a variety of funding providers. AusAid, some more economically developed governments, regional institutions, economics-focused projects and the EC have variously supported specific Fellowship posts. DFID has always been the largest contributor to the FS however, and UK universities training economists in international development are key recruiting grounds for potential Fellows. DFID (and HMG more widely) has employed ex-Fellows, finding their development experience a hugely valuable asset as they embark on being professional economists in government.

Without DFID funding, there would almost certainly be fewer junior economists employed as

Fellows in developing country ministries. Seeking another major source of funding would take some time and might be very difficult, as a break in the long-established funding partnership with DFID would raise concerns in other funders’ minds that the ODI FS is no longer effective and worth supporting. Fewer Fellows would lead to missed opportunities to better assess and then carry forward policy decisions by the governments of developing countries, with a real though modest loss of less poverty reduction.

Criteria against which to assess the Fellowship Scheme are the extent to which it:

Builds capacity for economic governance in weak and fragile states

Develops a supply of high quality development economists with valuable country experience, who mostly go on to work in international development.

These are not much affected by the funding mechanism that DFID uses to support the FS.

The efficiency criteria however does vary between options:

Maximising the efficiency of FS management, including minimising the administrative effort on both the OD IFS team and DFID of our funding

Option 1: Fund FS only through a centrally managed Accountable Grant.

The OD IFS team already provides full information to DFID and other partners of the operations of the FS, where postings are made and not made, the selection and recruitment statistics and process, the employers and Fellows’ feedback, etc. There is thus no change to the information which DFID potentially has access to through changing to just one central grant.

Advantages of Option 1 might include: less administrative effort for the FS management team, having just one DFID funding arrangement to manage, account for and report against; less total administrative effort for DFID, likewise. The FS team is trusted to make sound judgements on which countries and ministries to place Fellows in, consulting DFID and other partners/ colleagues in country as necessary.

Disadvantages of Option 1: It would entirely close off the flexibility for the next 3 years for

DFID country offices or DFID-funded programmes to ask the FS to place an additional

Fellow in a priority context. This would be very unusual i n DFID’s decentralised structure, where country teams are rarely prevented from working with whichever partners and aid instruments best suit the need and the country’s own preferences.

Option 2: Support only individual FS postings in specific DFID bilateral support countries.

In Option 2, DFID’s bilateral engagement with countries could more directly be said to include the Fellows posted there. This could be an advantage (seeing any links to the DFID efforts in country, possibly some informal pastoral care) and a disadvantage (Fellows perceived by their employing ministries to be connected to and perhaps loyal to DFID rather than primarily being employees of the ministry).

DFID has country knowledge and engagement only with a subset of all the low-income

countries that could effectively use an ODI Fellow. So limiting our funding of the FS to those with a bilateral engagement with DFID would likely miss some worthwhile placements and thus development impact.

Option 2 would require more frequent and detailed discussion with ODI on its placement decisions, and might be seen to compromise ODI’s control of their own scheme. With their being no compelling development case for focusing just on DFID-supported countries, the extra administrative effort would not be worth incurring.

Option 3: Central grant with the option of some country-level DFID funding

As a major funder of the FS, DFID cares that the FS continues to be highly effective and well-regarded, and ODI is happy to take on board constructive recommendations for change offered by DFID. The continuing focus on low-income and fragile countries and on the appropriateness of posts and Fellows, is enough to support development impact.

The recent review concluded that there was little gained in terms of in-country engagement or the quality of postings, when the decision to fund was by the DFID country office rather than funding coming from the core central grant. The extra administrative effort of running a separate country-level grant is best avoided wherever possible. Yet rather than insist upon one central grant, we conclude that the best option is Option 3, with most DFID funding provided by one central grant but the option remaining open – if needed – for countrylevel DFID support.

D. What measures can be used to assess Value for Money for the intervention?

The ODI FS was found to be highly cost-effective in the review of its last three years. There will be continued attention in the new period of funding to ensuring value for money through: a. Ensuring economy in the purchase of the few inputs needed for the FS: ODI will continue to seek best value for money flights for Fellows to and from their placements; competitive provision of health costs and insurance; modest and lowest-feasible cost housing for Fellows that is safe and secure. Salaries of FS management will be on

ODI’s normal graded salary levels; the salary supplementation paid to Fellows will continue to be rigorously reviewed against costs of living in the locations Fellows are posted to. b. Striving for efficiency : The FS management team will strive to organise visits to

Fellows in-country that minimise travel time and cost and achieve multiple objectives in each visit (ie pastoral care of current Fellows, reviewing how placements are working out, alongside discussions of new and replacement postings). The selection boards and briefing sessions are systematised, well-managed and efficient. The briefing (induction) sessions will have renewed attention to capacity building and will include security briefing and preparation, without requiring much additional expense of travel or accommodation for the new Fellows. c. Maximising effectiveness: Continued attention to the quality of Fellows selected and placed, and the quality of posts that they will be provided to, are the key drivers of effectiveness for the FS. On the latter, the FS management consults with development partners in country – DFID and others - about the highest priority,

d. suitable posts for Fellows during each cycle (and the performance of the Fellows already in that country). The renewed emphasis on capacity building by Fellows – their support to the learning of colleagues in the ministries they are working for, as well as the gap-filling capacity they directly provide - aims to drive the most development impact possible from each placement. Focusing on low-income and high-poverty countries is expected to best ensure that the FS brings strong developmental benefits.

Striving for cost effectiveness: Continued high demand for Fellows from employing governments – despite their bearing part of the cost of a placement, unlike the majority of Technical Assistance, will be a measure of the continuing need that the FS responds to.

E. Summary Value for Money Statement for the preferred option

Up to 40 DFID-funded posts, supported principally by a central Accountable Grant but with the possibility of some country-level DFID funding, represents the best value for money because:

ODI’s Fellowship Scheme is currently operating highly effectively and efficiently and there are no major changes required to ensure that it achieves value for money in the use of DFID and other partners’ funds

ODI will continue to focus on posts in low-income and fragile countries and on ensuring that Fellows selected and placements made are of high quality and potential development impact

DFID will be consulted in countries/ regions where we have country engagement, but the administrative burden of multiple contracts and grants will be avoided by striving to support DFID-funded placements through the central grant wherever possible.

Commercial Case

Indirect procurement

A. Why is the proposed funding mechanism/form of arrangement the right one for this intervention, with this development partner?

The ODI Fellowship Scheme belongs to the Overseas Development Institute. ODI employs the Fellowship Scheme staff using its standard staff salary scales, terms and conditions. ODI

Fellows are employed by the developing country governments and receive the local terms and conditions of employment direct from that employer, plus supplementation of salary and the costs of international flights and insurance funded by the ODI.

DFID’s support to the FS will be an Accountable Grant direct to the ODI.

B. Value for money through procurement

DFID considered the alternative providers of technical assistance in economic policy and management as part of the latest review of the ODI Fellowship Scheme for 2009-12. While there are a number of schemes that have followed ODI’s lead in the shape of their design, none has the FS’s track record nor its breadth of economic management posts with a twoyear placement model. Alternatives are shorter, more experienced technical expertise in budget planning and execution (eg the Budget Strengthening Initiative of CAPE, also based at ODI) at higher levels of remuneration; or focus only on a specific area of policy (eg trade policy capacity in

ComSec’s Hubs and Spokes programme).

There is fierce competition in the recruitment of Fellows, which ensures that the quality of

Fellows supplied remains high, as evidenced by the continuing strong demand from employing governments and the high employability of ex-Fellows both in developing countries and elsewhere in the international development community and beyond.

Competition is also built into the placement process, as posts that have not worked well with a Fellow will be scrutinised closely before ODI agree to any follow-on posting. Employing ministries in participating developing countries are aware that their reputation as employers is also shared among Fellows and others, so there is an element of competition in identifying realistic and worthwhile posts for Fellows to fill.

Having considered the alternative schemes providing junior technical assistance to developing country governments, DFID is confident that the Fellowship Scheme merited our continued support.

Financial Case

A. Costs of the Fellowship Scheme

SUMMARY BUDGET

Supplementation

Non-supplementation reimburse and 1% contingency

BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET

2012-13 2013-14 2014-15

£2,248,600 £2,686,800 £2,887,935

£409,720 £469,602 £494,590

TOTAL

BUDGET

4/12-3/15

£7,823,335

£1,373,912

REIMBURSABLE EXPENSES

X0001 £2,658,320 £3,156,402 £3,382,525 £9,197,247

ADMINISTRATION GRANT

X0002

SCHEME DEVELOPMENT

X0003

£577,436 £596,644 £616,554 £1,790,634

TOTAL F/S GRANT

£7,500

£3,243,256

£7,750

£3,760,796

£8,000

£4,007,079

£23,250

£11,011,131

Forecasting

The FS has a well-established financial structure and administration. The costs of the

Scheme are mostly predictable: salary supplementation and rent for Fellows in post; travel for FS staff and for Fellows; staff costs of the FS administration and management team.

Significant changes to these elements are mostly planned for (eg in the annual supplementation review exercise), or are known with a considerable lead time (eg where posts will be; any changes to ODI staff salary levels). The ODI FS team has a strong track record of forecasting the funding it will draw down in each period.

In this grant, we will move to a quarterly invoicing system but ODI will continue to provide each month a forecast of the expenditure for the current quarter and rest of the current financial year.

BUDGET 4/12-3/15

REIMBURSABLES X0001

Supp April-June

Supp July-Sept

Supp Oct-Dec

Supp Jan-March

Rent

Supplementation Total

Travel Total

Advance

End of Fellowship Payment

Pre Departure Allowances £150

Baggage Allowance out

Baggage Allowance back

Publications Total

Insurance

Medical

Selection expenses

Language Training Expenses

Briefing travel and Meals

Total Non-supplementation reimbursables

Contingency 1% reimbursables

TOTAL REIMBURSABLE

EXPENSES X0001

ADMINISTRATION GRANT

Placement Visit Costs

Staff Costs

Interviews

Briefing

Security Awareness

Publicity and Printing

Communications

Office space, ICT, HR

TOTAL ADMIN GRANT X0002

SCHEME DEVELOPMENT X0003

TOTAL F/S GRANT

BUDGET

2012-13

£395,700

£395,700

£499,350

£499,350

£458,500

£2,248,600

£60,800

£120,000

£81,600

£7,500

£10,800

£7,400

£6,300

£34,000

£25,000

£9,000

£5,000

£16,000

£383,400

£26,320

BUDGET

2013-14

£520,200

£520,200

£567,000

£567,000

£512,400

£2,686,800

£74,400

£120,000

£110,400

£7,500

£10,800

£9,600

£6,600

£40,000

£27,500

£9,500

£5,250

£16,800

£438,350

£31,252

£2,658,320

£40,000

£262,805

£6,000

£10,000

£10,000

£8,000

£1,500

£239,131

£577,436

£7,500

£3,243,256

£3,156,402

£42,000

£270,689

£6,200

£10,500

£11,000

£8,400

£1,550

£246,305

£596,644

£7,750

£3,760,796

BUDGET

2014-15

£582,750

£582,750

£582,750

£582,750

£556,935

£2,887,935

£80,000

£120,000

£120,000

£7,500

£10,800

£10,800

£6,900

£42,000

£30,000

£10,000

£5,500

£17,600

£461,100

£33,490

TOTAL

BUDGET

4/12-3/15

£1,498,650

£1,498,650

£1,649,100

£1,649,100

£1,527,835

£7,823,335

£215,200

£360,000

£312,000

£22,500

£32,400

£27,800

£19,800

£116,000

£82,500

£28,500

£15,750

£50,400

£1,282,850

£91,062

£3,382,525

£44,100

£278,810

£6,500

£11,000

£12,000

£8,800

£1,650

£253,694

£616,554

£8,000

£4,007,079

£9,197,247

£126,100

£812,304

£18,700

£31,500

£33,000

£25,200

£4,700

£739,130

£1,790,634

£23,250

£11,011,131

B. How will it be funded?

The FS will be funded entirely from programme funds. The benefits of the FS accrue principally to the employing governments in developing countries and through them to the citizens of those countries.

The Research & Evidence Division of DFID is providing the programme budget over this 3year grant period.

C. How will funds be paid out?

Funds will be paid quarterly in arrears against invoices supplied to DFID’s RED by the ODI

Fellowship Scheme which set out valid expenditure against the three elements of the grant set out above – reimbursable expenditures, administration and scheme development.

D. What is the assessment of financial risk and fraud?

Low. The majority of the funding for the FS is for ‘reimbursable’ items of travel (procured by

ODI for the Fellows through a travel agency) and salary supplementation to Fellows. The FS team’s salaries and the other management costs of the FS are fairly straightforward and are readily audited. The FS is audited annually by the external auditors appointed for the wider

ODI account audit. The FS has a strong track record of having its accounts audited without any concerns.

E. How will expenditure be monitored, reported, and accounted for?

RED’s normal practices will be followed forecasting, reporting and accounting for spending from this Accountable Grant. ODI will provide RED each month with a forecast of the expenditure for the current quarter and rest of the current financial year. Quarterly invoices will be checked and paid by RED. This summary financial data will be held in the ARIES financial management system in DFID, while the detailed accounts of FS costs will be maintained as now by the OD IFS Management using ODI’s normal financial management systems, and will be audited as a special account by the independent external auditors appointed by ODI each year. ODI will supply DFID with copies of the audited accounts each year.

Management Case

A. What are the Management Arrangements for implementing the intervention?

The ODI will continue to manage its Fellowship Scheme and will employ the core staff who manage the FS, provide office space and supporting services needed. The ODI FS managers will advise DFID’s Head of Profession for Economics and the RED Departmental Finance

Officer of developments in the implementation of the FS (such as significant staffing changes, significant country placement changes that are to be DFID-financed posts) as these arise.

DFID will supply an economist from our staff to serve on the selection panels, and will be invited to attend the briefing for new Fellows each year.

An FS Accountable Grant will be reviewed annually against the logframe and a deeper

assessment of its operations made in a review in the final period of the grant.

B. What are the risks and how these will be managed?

The recent FS review confirmed again that the FS is well-managed and well-understood, with established procedures and relationships with its partners in employing governments. The risks of the tried-and-tested FS approach are very low.

Two particular risks are pertinent however:

1. Leadership and delivery of the FS will be changing hands of the FS as a new Director is currently being recruited. The current Director will agree his departure (chosen retirement) once the new Director is identified; the current Director may continue some involvement in the FS and is willing to advise and handover as needed, and the other key FS staff are expected to remain in post, so this change should be well-managed.

2. Fragile and conflict-affected countries in particular and developing countries in general, have inherently volatile and uncertain institutions and there can be difficulties in the working and living conditions Fellows are placed in. The existing FS system of pastoral care is already good, but this will be strengthened and further supported by the conflict awareness training that all new Fellows will be provided with.

C. How will progress and results be monitored, measured and evaluated?

The FS team will keep DFID (via the HoP Economics) informed of major developments in the

FS, such as plans and agreements for new funding from other partners for the FS; staff changes; the outcomes of selection rounds; significant shifts in the postings composition for the FS. Information of this sort will be discussed as it arises.

Annual reviews will be the formal reporting against the logframe and objectives of the FS, which ODI will provide information for and DFID will finalise writing. Towards the end of this grant period, a review of the FS will be conducted to consider its effectiveness, efficiency and relevance, and to inform the consideration of any future funding to the Scheme.

Logframe

Quest No of logframe for this intervention: