The significance of architectural heritage for the construction of

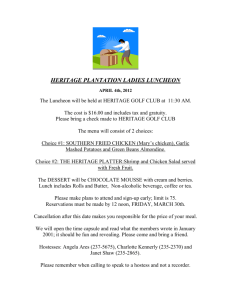

advertisement

Dear all, This essay will be developed as a part of the introduction in my thesis entitled ‘Architectural Heritage: as Culture and Cultural Policy in Europe 1960s-1990s, Culture, Nation and Community, Whose Buildings are They? The brief scope of my thesis is as follows: ***************************************************** The European Union, a grand political project of the post World War II period, has searched for new ways to advance the integration process since the 1960s, making culture a key concept in that process. This thesis presents an analysis of the ways the EU has sought to build Europe by using concepts of culture and architectural heritage. In so doing, it will propose a new way of looking at the EU’s transformation from the 1960s to the 1990s, namely the cultural construction of the ‘new Europe’. It will examine the European Union’s ways of exploiting the power of architectural heritage upon the integration process. The primary idea is that architectural heritage has been exploited in threes ways: as a representation of common European culture; as a metaphor for building the ‘new Europe’, and as a key aspect of development. The interplay of these functions serves as a dynamic force to insert the ‘idea of Europe’ in the European Union’s denationalization process. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF ‘THE NEW EUROPE’ As far as collective memory of the past plays a significant role in creating the sense of belonging to any communities among their people, political regimes practically exercise their power in the process of making the past in which artefacts are chosen to be its representation. Similarly, the European Union has endeavored to construct ‘the new Europe’ by creating a collective memory known as the ‘common European culture’ in the process of which the concept of architectural heritage has become seminal in the representation of common European culture. Architecture by its nature mirrors the shadow of power by two levels. Firstly, the power of architecture itself creates human-being’s dwellings and space. It becomes a built environment which influences people’s lives. Secondly, it represents power of any political regimes in constructing their communities through styles and the function of architecture. Metaphorically, architecture as a structure of form is the very symbol of power and bureaucracy since its physical appearance is a huge form of something The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 2 powerful, important and complex. Undoubtedly, any political regimes, including the European Union are attracted by the language of architecture and select it to be a representation of European culture. However, not every architecture is selected to be the representation of common European culture. In the selection process, the idea of heritage is concerned. The term ‘heritage’ is also similar to architecture in the sense that it associates with power—who defines what is heritage. Heritage as collective inheritance is a symbol of a community civilization and culture. Political power, particularly nation state takes a dominant role in defining what is national heritage. By the same token, a new political power like the European Union has endeavored to build up the Community by getting involved with architectural heritage. Nevertheless, the relation between supra nation and architectural heritage in a contemporary period is characterized not only by political power’s vision but also by the on growing trend of the socioeconomic benefit of heritage industry which becomes a main actor in shaping the perception of the past. More importantly, from the nineteenth century onwards, architectural heritage has long functioned as a symbolic factor in defining the nationstate, but the European Union has endeavored to promote national architectural heritage in order to celebrate ‘the common European culture’ or ‘the European unity’. Such a contradiction, thus, proves to be interesting in seeing why architectural heritage is so important for the construction of ‘the new Europe’. Herein, the significance of architectural heritage is the point of departure and it will be analyzed into three main topics: the rise of the term ‘heritage’ in the post war period; the importance of architectural heritage for defining nation state, and ‘the new Europe’. As heritage become a main actor in shaping the landscape of the past, the rise of heritage and heritage industry needs to be clarified. My argument is that the term ‘heritage’ which has been widely used nowadays is a rather new concept, it only emerged and has been formulated since the 1970s. Furthermore, the widespread use of the term ‘heritage’ was influenced by the international movement and the socioeconomic element of heritage. Subsequently, the significance of architectural heritage shall be analyzed in the context of nation state and supra-nation. Why architectural heritage is important to the construction of Europe is another principle question. The hypothesis is that the European Union assumes the role of a nation state and imprints its power over the reinterpretation of European history by defining what the architectural heritage of Europe is. However, the involvement of the European Union The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 3 in the field of architectural heritage and the way of using this architectural heritage is more complex than that of the nation state. Heritage The term ‘heritage’ has gradually arrived in vogue since the 1970s. Originally, it meant ‘that which has been or may be inherited; any property, and esp. land which develops by right of inheritance’.1 Before the 1970s, the terms ‘cultural property’ and ‘historical monument’ were more applied to historical and cultural assets. In `1954, UNESCO adopted a convention2 to protect cultural assets from armed conflict by selecting the term ‘cultural property’. In the convention, the term heritage is mentioned as an alternative term of cultural property. Weber3 proposes that the term heritage substituted the concept of historical monument in the 1970s. This proposal is somewhat reasonable since before the 1970s, the term ‘historical monument’ was widely used at the international level, applied to architecture as artistic and historical value. At that time, the international movement to protect historical and cultural property was more concerned with the endurance of the past by using the term ‘historical monument’. The most important witness is the Venice Charter (1964) which uses the term historical monuments and sites meaning that, ‘The concept of an historic monument embraces not only the single architectural work but also the urban or rural setting in which is found the evidence of a particular civilization, a significant development or an historic event. This applies not only to great works of art but also to more modest works of the past which have acquired cultural significance with the passing of time’4 In this Charter, the term ‘heritage’ was used as a collective term referring to human being property without any significance. 1 The Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. 5 Oxford University Press, 1970, p.242. 2 The Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (The ‘Hague Convention’), with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention, as well as the Protocol to the Convention and the Conference Resolutions, 14 May 1954 3Weber, 4 Raymond. ‘Editorial’. European Heritage. No. 3, 1995, p.1. http:culture.coe.fr/Infocentre/pub/eng/epe ‘The Venice Charter’. http://www.icomos.org/docs/venice_charter.html. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 4 The term ‘heritage’ began gaining its importance in the European Conference of Ministers held in Brussels in 1969. In this conference, it was juxtaposed to the term ‘monument’ as seen in the recommendation namely, Recommendation of the European Conference of Ministers Responsible for the Preservation and Rehabilitation of the Cultural Heritage of Monuments and Sites. Nevertheless, it became an international term in 1972 when UNESCO announced the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1972. Later, the Council of Europe through the Committee of Ministers also used the term heritage by heading its charter concerning architecture ‘European Charter of the Architectural Heritage’ (1975). Besides, in the European Union’s documents concerning culture in the 1970s, the term ‘heritage’ was used as a representation of European culture.5 The outgrowth of the concept of ‘heritage’ since the 1970s has had three new characters. First of all, it includes natural resources to be natural heritage such as landscape, natural sites, outstanding parks and etc. Secondly, for cultural heritage, the meaning is very broad as the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage defines that cultural heritage means, ‘Monuments: architectural works, works of monumental sculpture and painting, elements or structures of an archaeological nature, inscriptions, cave dwellings and combinations of features, which are out standing universal value from the point of view of history, art or science; Groups of buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, their homogeneity or their place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art and science. Sites: works of man or the combined works of nature and man, and are including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view’. 6 Thirdly, the concept of heritage has been broadened to include recent cultural assets and buildings such as industrial heritage—buildings in dock land, tools in old factories, coal mine sites etc. This is a new phenomenon in the sense that artistic value is not the only criteria in order to judge which artefact can be called a heritage. The practical value of artefacts becomes another important concern. Heritage in vogue: factors 5 Please see details in the European Parliament’s reports and debates in the 1970s. 6 UNESCO. ‘Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage 16 November 1972’. Conventions and Recommendations of UNESCO Concerning the Protection of the Cultural Heritage. Geneva: UNESCO, 1983,p.80 The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 5 1. The increase of international solidarity in protecting the world’s properties The idea of protecting cultural and natural properties has gradually become more international in the post war period since almost all of Europe were affected by the war. It brought about the increasing awareness of protecting cultural properties at a national level. Furthermore, natural disasters such as flood which submerged outstanding heritage and artistic value and cities, was an important catalyst to formulate the international solidarity to protect the world properties. The first movement was the protection of the Abu Simbel and Philae temples in Egypt which were greatly affected by the decision of the Egyptian government to construct the Aswan High Dam. The construction of the Aswan High Dam could cause floods in the valley containing these two temples. The two temples were also ‘dismantled and moved to dry ground and reassembled’.7 In 1959, UNESCO launched international campaigns to protect the temples. ‘The campaign cost approximately US$ 80 million, half of which was donated by some 50 countries, showing the importance of nations’ shared responsibility in conserving outstanding cultural sites’.8 The concern with the temple of Philea still appeared in 1966 as seen in the Times which published a photograph of the temple with the description that, ‘The water of the Nile partly cover the temple of Philea, one of the Nubian antiquities affected by the Aswan High Dam. The water is now likely to remain at this level’.9 Another important event was a big flood in Florence and Venice on the 4th November 1966. Consequently, ‘…all the streets of Florence were torrents of rushing water as the River Arno broke its banks. Cars were lifted bodily and buried beneath water and mud’.10 In Venice, the level of water was over 2 feet high and other areas around were destroyed by the flood. Apart from physical damage of these two cities, all buildings and works of art were in severe danger. Saving Florence’s art became a huge international issue since it was far beyond the city’s and the Italian government’s capacity to solve the problem alone. It started when ‘the city of 7 UNESCO. World Heritage Kit. http://www.unesco.org/whc/5history.htm. 8 Ibid. 9 The Times, November3, 1966. 10 ‘Storm Havoc Causes 16 Deaths in Italy Floods Hit Florence and Venice as Country’s Links are Cut’ The Times. November5, 1966. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 6 Florence appealed to the world…to help save its flood-damaged art treasures’.11 Moreover, leading newspapers in many countries continued reporting news about the flood and the art treasure in danger. The formulation of international solidarity to protect world properties is represented in newspapers. For example, the Times published a full page article, the Ruin of Florentine Art: What the Floods have Cost Civilization, by John Sherman 12 who wrote that, ‘…the effects of this flood will continue, even for years; the weakening of foundations will go on, rising damp in the wall will affect frescos, violent humidity changes will do further damage to panel paintings or furniture… A definitive assessment of the destruction will never be made. Similarly, no assessment can be given of the cost of whatever restoration can be done. One may only say that if it is to be done within a generation the cost is many times greater than any one country can bear.’13 Another example is an editorial article in the Times saying that, ‘To this must be added the cultural losses which no money can replace and which are only now in process of being accurately assessed... Britain’s ties with Italy are of very special sort, and imply special obligations. Leaving aside the dept that all European countries owe to Rome and Italy in general, Britain’s special links over the past four centuries—and more—lie in the things of the mind and of the human spirit’. 14 Furthermore, this idea was transformed into concrete action to protect Florentine art-the international committee was then set up to hasten restoration measures. People from everywhere came to save Florence by giving a helping hand in moving all of the works of art from water and mud to safe places. UNESCO launched an international campaign for raising funds to restore art and the architectural heritage in Florence and Venice. All of these experiences aroused awareness of the erosion of world properties and the creating of the sense that all national properties are also world properties. In this way, the term property does not serve the new rising sense, but the term ‘heritage’ functions well as a neutral term for international inheritance. The world solidarity was also shaped by the UNESCO initiatives, the World Heritage. The World Heritage is a project set up since 1972 for the reason that ‘the cultural heritage and the natural heritage are increasingly threatened with destruction 11 ‘Italian Petrol Tax for Flood Fund’ The Times November 9, 1966. 12 Sherman, John. ‘The Ruins of Florentine Art: What the Floods have Cost Civilization’ The Times November23, 1966. 13 IBID 14 ‘Counting the Cost’. The Times November 17, !966. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 7 not only by the traditional causes of decay, but also by changing Social and economic conditions which aggravate the situation with even more formidable phenomena of damage or destruction’.15 UNESCO has operated the Word Heritage initiative by setting up the World Heritage Fund and the World Heritage Committee. The Committee annually announces the world heritage list by selecting from the cultural and natural sites. It also makes a list of heritage in danger each year in order to create the awareness of protection of heritage among people all over the world. The longterm plan of the World Heritage initiative increases the sense of protecting heritage in a national and international context. More importantly, it makes the term ‘heritage’ popular for referring to natural and cultural assets. 2. The increasing socio-economic trend of heritage The term ‘heritage’ acquires its importance in the contemporary period, having become an industry, a main witness is the increasing numbers of heritage registered by states. For example, in Ireland, ‘during the decade 1970 to 1980, the number of monuments given state protection …doubled, to 2,055 sites, with substantial increase in listing and preservation order’16. The intervention of architectural heritage of historical interest at that time is not limited only by the Irish government, but expanded to local agencies which can be seen from the number of sites and buildings in that decade, there were around 60, 000 buildings of historical interest, but ‘one in ten of which were considered to be of national or international significance’.17 It means that the nine percent of architecture of historic interest in Ireland was invented by local agencies in order to attract tourists which was a new approach to activate local economies. Heritage has become an important commodity which brings about prosperity in economic terms. This is very much influenced by the economic circumstances in the 1970s and the 1980s when the fragile situation of the European economy worsened because of the oil crisis in 1973. All European countries encountered 15 UNESCO. ‘Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage 16 November 1972’. Conventions and Recommendations of UNESCO Concerning the Protection of the Cultural Heritage. Geneva: UNESCO, 1983,p.79. 16 17 Prentice, Richard. Tourism and Heritage Attraction. London: Routledge, 193, p.23. Ibid. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 8 inflation, balance of payment difficulties, currency disorder, rising unemployment etc. Even though the problem of economic recession was solved to a certain extent in the late 1980s, the rate of unemployment was still high. In contrast to the decline of the heavy industry, tourism grew and became one of the main income in many countries. More importantly, tourism increased jobs in various ways, i.e., in accommodation business, souvenir markets and heritage sites. In the light of this circumstance, tourist attraction is a chief issue. As a result, most European countries actively created an image of their capital cities and provinces by adding list of national heritage and promoting them as tourist attractions. Moreover, many sites which related to mankinds’ past and activities which had not been heritage such as coal mines and other industrial sites were created to be heritage by private companies. Furthermore, heritage industry expands since it is the commercialization of nostalgia. Changes in European societies during the 1970s and the 1980s enhanced this feeling of nostalgia, as Lowenthal wrote ‘dissatisfaction with the present and malaise about the future induce many to look back with nostalgia, to equate what is beautiful and livable with what is old or past’.18 3. The expansion of state heritage into popular culture Next to the rise of the appropriate terminology, heritage has acquired an additional new significance in the contemporary world, by being recreated as popular culture. I agree with Prentice who proposes that ‘…what might be termed an official heritage of state monuments increasingly expanded into popular culture’.19 In other words, heritage, as artefact, initially functioned as a device of power in the Roman Empire and during the formation of nation state, heritage such as architectural monuments symbolized the sense of citizenship and royalty to the nation. When tourism spread in the 18th century, the appreciation of state heritage dominated tourists interests and it still continued until the early 20th century. At that time, investment in heritage was mostly in the hands of state. The contention of heritage between private sectors and state was not apparent. 18 Lowenthal, David. Our Past before Us. Why do We Save It?. London: Temple Smith, 1981, p. 216. 19 Prentice, Richard. Tourism and Heritage Attraction. London: Routledge, 1993, p. 23. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 9 However, during the post war period, in particular, from the 1970s onwards, heritage has become a popular culture in two ways. Firstly, it represents various stories of popular history and local history. The increasing demand of new heritage attractions for the tourist industry opens up space for local memories to be represented through heritage. Secondly, heritage in a broad sense has become a mass leisure. The new forms of heritage invention and consumption expand the new meaning of heritage to people. While state heritage is highly invented for political purpose, heritage as a popular culture is created to respond the tastes of consumers, markets and vision of investors. This trend dramatically increases. Consequently, private sectors and even nation states take an active role in turning heritage into a popular culture. This phenomenon corresponds with the changing of leisure time in European society, the rebirth of cultural consumption, the ongrowing of global tourism and the European force. During the post war period, the rate of leisure time in many countries was higher than previously, due to the fact that the launching of the full wellfare state together with the decline of the fixing of load long working hours enabled workers and housewives to have more free time for holidays. Furthermore, the rebirth of cultural consumption from the 1970s onwards has brought about new habit and invention of cultural goods. The growing of global tourism is another factor which activates the tourist industry in Europe. One of the images of Europe is a big museum which is the most attractive factor in drawing tourists from other parts of the world such as Japan, Korea and Latin American countries to visit Europe. What they want to experience is European heritage. For the European force, it means the European Union’s role in activating tourism in Europe which has a specific character-- the European Union tries to promote intra-European tourism so as to promote intraEuropean understanding. All flexible measures concerning free movements of labor and travelling set up by the European Union are potential since ‘more Europeans are choosing to visit their continental neighbors than ever before in history’ 20 Furthermore, the European Union supports the invention of new heritage such as in agricultural areas and in the industrial decline areas through various budgetary instruments. This activity is a contributor in making heritage a popular culture. 20 Ashworth, Gregory J. ‘Heritage, Tourism and Europe: a European Future for a European Past’ in Hurburt, David T. Heritage, Tourism and Society. Pinter, 1995, p. 77. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 10 Architecture and architectural heritage and its relation to power: nation-states models of exploiting architectural heritage Architecture is a built environment which is designed and constructed by man. It comprises both aesthetic and practical functions which provides human-being with an opportunity to express their ideas regarding their relationship with the outside world. In other words, it signifies the ways human-beings manage spaces by creating architectural mirrors of how they think about themselves and the outside world. Architecture is always considered as a symbol of human civilization since its elements such as style and function change along with the development of human societies. In ancient times architecture was designed and built to meet simple needs of humanbeings, but later its design and the construction methods became more complex. In this development, architecture is associated with political power due to the fact that it conveys collective memories through its artistic and practical functions. This is very much concerned with the development in European society where collective memories are found upon material objects. The origin of this memory tradition sprang up in the Renaissance period and was then formulated in Western society. Adrian Forty (1999) pins down this argument that ‘whether natural or artefact can act as the analogues of human memory. It has been generally taken for granted that memories formed in the mind, can be transferred to solid material objects, which can come to stand for memories’.21The outgrowth of public museums from the mid nineteenth century onwards has been a vivid case which shows that the western society as a whole has the tendency to believe that material objects represent their collective memories. Just as material objects stand for the fragile memories of human beings, architecture with its virtue of solidity is undoubtedly a long standing symbol of collective memories. From this point, architecture attracts political power in order to mobilize their vision of the world through its language. To a certain extent, it represents the vision of political power in two ways-- representing the political power’s idea of modernity and its vision of using the past for the sake of the present. Put in another way, architecture is a significant medium for the political power to 21 Forty, Adrain. ‘Introduction’ Forty, Adrain and Kuchler, Susanne. The Art of Forgetting. Berg, 1999, p. 2. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 11 express their self-interpretation. In turn, with time, the specific styles of architecture, i.e., Renaissance, Gothic etc stand for memories of the period in which this architecture was built. Therefore, political power has possibilities to apply or imitate some previous architectural styles, which serve its vision of the world and power, to be the architecture of its own time. Furthermore, architecture by its own nature is symbolic in that it stands for something else. More importantly, symbolic interpretations are imprecise since part of their meaning is subjective, allowing for new reinterpretations. Thanks to its symbolic function, architecture is a flexible medium in which political power can use its language and at the same time contribute new meanings for a political purpose. A good example of this explanation is the way in which the nation-state exploits architecture and architectural heritage. In this heading, the discussion will be furthered by arguing about reasons why analyzing the significance of architectural heritage to the construction of the new Europe that can not be detached from looking at its significance in defining a nation-state. Then, an aspect of nation-state, a political imagery will be discussed as a foreground in order to better deduce an understanding of why architecture becomes a representation of power. The last point in this heading is concerned with the symbolic function of architecture and architectural heritage for defining the nation-state. Why is the model of architectural heritage as defined by the nation-state significant for the construction of ‘the new Europe’? First of all, the European Union has endeavored to represent itself as a new kind of community, as it calls itself the ‘European community’. The concept of new political community is unavoidably contestable with the concept of long-established community, in particular, the nation-state. As a new Community, the European Union has been analyzed from the point of view of political and economic development as seen in much of the literature dealing with it. However, a community, as argued by Anthony Cohen (1989), is not only a structural construction of a political constitution, but rather a mental construction in the sense that the community needs to make itself ‘exist(ing) in the mind of its member’.22 In this process, symbolic factors such as 22 Cohen, Anthony. The Symbolic Construction of the Community. London: Routledge, 1989, p. 98. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 12 boundaries and collective memory of the past playing a role as a share identity or imagery among members of community. This assumption is not only the academic’s construction, but the European Union itself is also aware of constructing the Community in its people’s minds and tries to forge the sense of belonging among its citizens. This can be traced back to 1976 when the Tindemans Report23 discussion on this point is that, ‘No one wants to see a technocratic Europe. European union must be experienced by the citizen in his daily life. It must make itself felt in education and culture, news and communications, it must be manifest in the youth of our countries, and in leisure time activities’.24 Later, other political circumstances increased the European Union’s efforts to create the imagined community. For example, it tried to use symbolical tools to convey the idea of the community as seen from the launching of a five-year programme of architectural heritage in 1985; producing the Community flag and song; promoting the community boundary by distributing the community maps in Info-point Europe and setting the programme called ‘A People Europe’ so as to make a European public sphere by convincing its citizen how ‘Europe’ serves their daily life. 25 Therefore, the European Union has become a new kind of community parallel to the community of the nation-state. Secondly, by constructing an imagery of the new community, the European Union has endeavored to use architectural heritage symbolizing the common culture of the new Europe. It initially imitated the nation state’s model of exploiting architectural heritage—it used the patronage system by sponsoring the preservation of significance architectural heritage such as the Parthenon in Greece and Chiado in Lisbon and launching an annual theme of supporting preservation through a project carried out by its organizations. Nation-state: a political imagery 23 The Tinedemans Report is a report written by the Prime minister of Belgium, Tindemans who was requested by the European Council to revise the current stage of the European Union and to propose an idea how to further the integration process. This report was later quoted and became one of the important guidelines of the European Union in proceeding many policies, including cultural policy. 24 The European Commission. ‘European Union’ Report by Mr. Leo Tinedemans, Prime Minister of Belgium, to the European Council. Bulletin of the European Communities. Supplement 1/76, p. 12. 25 Please see an example of this effort in Fontain, Pascal. A Citizen’s Europe. The European Commission, 1993. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 13 In social sciences, there is a difference between the term ‘nation’ and ‘state’ which is needed to be clarified at the beginning. State means a unit of territory ordered by sovereign power. It is also a ‘self governing set of people organized so that they deal with others as a unit’.26 Whereas nation means the spirit of state which includes its existence in its people’s minds and also the sense of belonging among its citizen. Herein the term ‘nation-state’ is used as the co-meaning of the terms state and nation, as Guiberneau defines that, ‘The nation-state is a modern phenomenon, characterized by the formation of a kind of state which has the monopoly of what it claims to be the legitimate use of force within a demarcated territory and seeks to unite the people subjected to its rule by means of homogenization, creating a common culture, symbols, values, reviving traditions and myths of origin…’. 27 By this definition, it links to the latest model of the nation-state building (Anderson 1983) which attaches much importance to the role of imagery. According to Anderson, the nation-state is neither deriving from gods will, nor a natural phenomenon. Rather it is a political imagination which is only developed in modern times. There are three ways in which it is imagined—it is imagined as limited; sovereign and as a community. In other words, no matter how much of the citizen is in a nation, it is limited by its boundary. Nation is imagined as a sovereign since it symbolizes the freedom of human history which is a inheritance from the Enlightenment intellectual development. Nation is imagined as a community since it ‘is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship….(O)ver the past two centuries, for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willing to die for such limited imaginings’.28 This approach perfectly corresponds with what Cohen points out that a community building like a nation-state ‘can no longer be adequately described in terms of institution and components, for now we recognize it as symbol to which its various adherent impute their own meanings’.29 Therefore, a nation requires devices to create its imagined community. The role of symbol; ritual and artifact intervenes 26 Kuper, Adam and Kuper, Jessica. ‘State’ in The Social Science Encyclopedia. London: Routledge, 1996, p. 835. 27 Guibernau, Montserrat. Nationalism. The Nation-State and Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. Polity Press, 1996, p. 47. 28 Benedict, Anderson. Imagined Communities. London: Verso, 1983, p. 16. 29 Cohen, Anthony. The Symbolic Construction of the Community. London: Routledge, 1989, p.74. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 14 at this point. The process in which these devices operate upon the constructing of the imagined community in people’s minds lies in the relation of power and invented memories and tradition. Architectural heritage and its symbolic function for defining nation-state Architectural heritage becomes one of the symbolic device on which political power projects its vision of the world and conveys political message concerning images of the community and forms of the imagined community in two ways. Firstly, it transmits the self-conscious of the political regime through its style and function. This process can be considered as the political regime’s way of expressing the idea of modernity. Secondly, it is a representation of the idea of a political regime which bases its legitimization on an identification with a past glory. For the former, the case of the construction of the Opera House in Paris by Napoleon III is a good example. Penelope Woolf (1988) analyses the belief which was widespread among writers, architects and leaders in the nineteenth century that architecture conveys the French civilizational spirit. The Opera House was, thus, planed under this circumstance. Napoleon III, with the aspiration to build up the image of the second empire and to enhance the reputation of Paris as a cultural capital, wished to express the idea of modernity formulated in his empire through the medium of architecture: location, style and function. As Woolf points out ‘by locating the Opera at the centre of a district that was itself the heart of Paris, just as Paris was the artistic capital of France, Europe and even the world, the imaginative power of the monument would rest on layer of symbolic meaning’. 30 The Opera House was designed by an architect, Garnier who was highly concerned with what he was to design not only to create a style of ‘his age but also characteristic of the whole nineteenth century’.31 Therefore, the style of the Opera House stands for ‘modern art as realistic, a response to materialistic, individualistic era’.32It also demonstrates the ideas of elegance, luxury and prosperity which is witnessed by its function serving as 30 Woolf, Penelope. ‘Symbol of the Second Empire: Cultural Politics and Paris Opera House’ in Cosgrove, Denis and Daniels, Stephen. The Iconography of Landscape. Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environment. Cambridge Universitry Press, 1988, p. 223. 31 IBID, p. 224. 32 IBID, p. 225. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 15 a house of the grand opera. The opera in that time was a symbol of high appreciation of materialistic value such as prosperity and luxury. In sum, architectural heritage, as a built environment symbolizes the empire which was planned by political leaders. However, the symbolic factor which architecture stands for does not only limit as the interrelation between leaders, architects and architecture, but it touches people and transmits its message by being their environment and a place where they can have activities in their daily life. For the second point, architectural heritage represent the political regime’s self representation through the glory of the past. The fascist regime of Mussolini in Italy is a perfect example. For Mussolini, as quoted in Gentile, ‘Monumental architecture which lasts for centuries is a symbol of the permanence of the state’.33 The fascist regime endeavored to construct its self representation by exploiting the past, in particular, the myth of Rome which Italian people were long familiar with. It depicted the zenith epoch of Roman history, the Augustean’s era by emphasizing his leadership. The reinterpretation of the Roman civilization, established ‘the regime as the legitimate representative of the Italian nation’.34 Architectural heritage plays a significant role in this process since it symbolized the glory of Rome. The fascist government commissioned the support of the restoration of Roman architecture by neglecting other architectural style such as the Middle Age architecture. Similarly, the government ‘commissioned archaeological digs in search of the ruins of its Rome. During the excavations, buildings belonging to the middle ages were found and immediately destroyed in order to let ancient Rome predominate as original witness of fascism’s glorious destiny’.35 Furthermore, when the fascist government organized exhibitions demonstrating the greatness of the regime such as the grand exhibition in 1924. Architects applied classical style of architecture such as arches and columns to be the theme of the whole exhibition structure. The significance of architectural heritage for the construction of ‘the new Europe’ 33 Gentile, Emilo. The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy. Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 122. 34 Falasca-Zamponi, Simonetta. Facism Spectacle. The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini’s Italy. University of California Press, 1997, p. 94. 35 IBID, p. 93. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 16 Architectural heritage was recognized as a device to construct the new Europe in 1974 when the Liberal and Allies Group, a political party in the European Parliament, proposed to the European Parliament and the European Commission to create the common European culture by preserving architectural heritage. The incentive behind this phenomenon can be discussed in two ways. First of all, it lies in the development within the European Union. At that time, the European Union elites wish to advance the integration process by using the concept of culture. For example, in the Hague Summit (1969), the heads of states for the first time regarded ‘Europe’ as an ‘exceptional seat of development, culture and progress; that it was indispensable to preserve it’.36 Later, the final declaration of the Paris Summit (1972) contained the observation that economic expansion is not an end in itself and ‘special attention will be paid to non-material value…’37 Secondly, according to the presentation of Lady Elle, the representative from the Liberal and Allies Group38 to the European Parliament, architectural heritage is a symbol of the European common culture. Furthermore, the reasons to preserve architectural heritage given by Lady Elle correspond to the increasing of international trend to protect heritage—the term ‘heritage was used and the decaying problems of heritage were mentioned. The European Parliament was the first organization of the European union which became actively involved with architectural heritage activities—it urged the European Commission to take a visible role in this field. The European Commission39 is the main organization of the European Union who has been in charge of implementing all policies, including cultural policy, concerning architectural heritage. Within the European Commission, there are main administrative units in charge of separated subject matters called Directorate General (DG). Each DG is named by a number such as DG I or DG II. In the case of architectural heritage, two DGs are relevant-- the first one is called the Directorate General X (DG X) taking responsibility for media, education and culture. Another one is the Directorate 36 Bulletin of the European Communities 1-1970. ‘The Hague Summit’, p. 7. 37 Bulletin of the European Communities 10-1972. ‘The First Summit Conference of the Enlarged the Community, p. 15-16. 38 Please see details in Debates of the European Parliament, No. 176, May 1974. 39 The European Commission is ‘sometimes referred to as the ‘civil service’ of the European Union, (it)…is a unique amongst international bureaucracies by virtue of its combination of administrative, executive, legislative and responsibilities’. (Bainbridge, Timothy. The Penguin Companion to European Union. Penguin Book, 1997, p. 160.) The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 17 General XVI (DG XVI) whose main responsibility is regional policy. Obviously, the DG X is a major organ of the European Commission who directly launches cultural programmes, particularly, it set up the long-term architectural heritage programmes over the last three decades. In contrast to its image which is seemingly far concerned with architectural heritage matters, the DG XVI is a highly potential unit in supporting architectural heritage preservation and creating new heritage such as urban heritage, architectural heritage in rural and industrial decline areas through it regional development programmes. The DG XVI is in charge of regional policy by mobilizing a big amount of budgetary instruments of the Community called the Structural Fund which bring about a great impact on architectural heritage. From these facts, several questions concerning architectural heritage and ‘the new Europe’ arise. Firstly, what is ‘the new Europe? Secondly, what is the significance of architectural heritage for the new Europe? ‘The New Europe’ ‘The new Europe’ is a political discourse which emerged and was formulated along with the development of uniting Europe, known as the European Union. As an idea, uniting Europe did not spring up for the first time at the end of the Second World War. European scholars had long contemplated European unification but the lack of a strong impetus prevented such an idea from becoming reality. The Second World War confronted people in Europe, from citizen to political leaders, with devastated situation. The idea of uniting Europe was revived as a result. As a discourse, ‘the new Europe’ appeared when political leaders like Jean Monnet said ‘Europe has never existed’.40 ‘Europe’ at that time was mentioned as an expected unity which would arise from the devastation of the war. ‘Europe’ was waiting to be born and nurtured as envisaged by Robert Schuman, ‘Europe will not be made all at once, or according to the single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first creat de facto solidarity’.41 The discourse of ‘the new Europe’ spread all over the continent and functioned as a collective belief and hope for the future, for a new kind of 40 Monnet, Jean. ‘Memorandum to Robert Schuman and Georges Bidault’ in Nicoll, William. Building European Union . A Documentary History and Analysis. Manchester University Press,.1950, p. 43. 41 Schuman, Robert. ‘The Declaration’ in Nicoll, William. Building European Union . A Documentary History and Analysis. Manchester University Press,.1950, p. 44. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 18 international cooperation beyond nation state, bringing about a new era of prosperity, peace and solidarity back to Europe. As a discourse, ‘the new Europe’ is a story in itself which needs more new devices to achieve the greater Europe for two reasons. Firstly, by its very nature the European Union is based on the way in which nation-states come closer to each other under certain political and economic conditions. In order to be a part of new Europe, Member States’ backgrounds and their commitment to being a part of Europe is an important dynamic force of the European Union’s growth. Therefore, searching for a new dimension is seemingly a method to advance the uniting of Europe and maintain the relationship between the European Union and Member States. Secondly, the discourse of ‘the new Europe’ is highly dependant upon the idea of progress. For example, in the Declaration of the European Identity (1973), the idea of progress is represented that, ‘They have defined their European identity with the dynamic nature of the Community in mind…the nine have their political will to succeed in the construction of a United Europe’.42 The idea is reiterated again in the Tindemans Report that, ‘…European Union is a new phase in the history of the Unification of Europe which can be achieved by a continuous process…I am convinced that this Europe, a progressive Europe, will lack neither power nor impetus’.43 And then in the European Single Act, the idea of progress has been stressed that, ‘the European Communities and objective to contribute together to making concrete progress towards European unity European Political Cooperation shall have as their’.44 ‘The new Europe’ serves as a shared hope, seemingly far reaching , but it is supposedly capable of becoming true in the future. In turn, when ‘the new Europe’ reaches a certain development, it needs a greater progress which correspond to the changing circumstances so as to make and keep ‘Europe’ alive. The significance of architectural heritage for ‘the new Europe’ The reasons why architectural heritage is so important to the construction of ‘the new Europe’ is embedded in the power of architectural heritage and in the vision of the European Union on constructing the Community from a cultural aspect in order 42 The European Communities. ‘The Declaration on the European Identity’ Bulletin of the European Communities. No. 13, 1973, p. 118-119. 43 The European Commission. ‘European Union’ Report by Mr. Leo Tinedemans, Prime Minister of Belgium, to the European Council. Bulletin of the European Communities. Supplement 1/76, p. 12. 44 The European Communities. The European Single Act. 1986, p. 7. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 19 to solve the problem of legitimacy and to strengthen the integration process. As a forementioned heritage is a new phenomenon in contemporary Europe, it become a main actor in economic development, as one of the European Union’s publication notes about its cultural projects in the framework of regional policy that, ‘These projects are meant to help to create or safeguard jobs, and to stimulate local and regional economies. They do so… by creating jobs in the cultural or heritage sector…’ 45 Moreover, architectural heritage and its assumed role as a representation of collective culture allows the new political power like the European Union to convey and enhance the idea of ‘Europe’ to its people. In other words, architectural heritage as a material object which consists of political and economic functions provides the European Union with a way in which on one hand it can promote the new collective identity called ‘European identity’, and on the other it can make a profit from this identity for development and economic purposes. The European Union’s vision to strengthen the integration process by using the concept of culture appeared when the European Union wished to advance the integration process from the late 1960s onwards. At that time, the integration process achieved its goal of bringing prosperity back to Europe. However, two new circumstances, the economic crisis in the 1970s and the plan to enlarge the Community brought about uncertain future. As a result, the nine Member States at that time wished to revise its common political goal by declaring ‘the Declaration of the European Identity’ in 1973. This declaration was rather an external identity of Community which was based on the political will and a common European culture. The cultural aspect suddenly gained its importance on the European Union’s agenda. Then it became even more significant when the European Union found itself lack in legitimacy since political situations such as the election to the European Parliament (1984) and the referendum of the European Single Act (1986) and ratification process of the Treaty of Masstricht (1992) proved that people in Member States are far more concerned with the Community’s future. The European Union is only a remote bureaucratic. The problem of legitimacy lies in the problem between the Community and its citizens. This problem is rather complex--as the European union estimates itself, there is no ‘European consciousness’. Nation-states dominate their citizens’ royalties. Here 45 The European Commission. Investment in Culture: an Asset for all Regions. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European communities, 1998, p. 5. The Significance of Heritage/ M. Jewachinda 20 comes the concept of culture and architectural heritage to be political mediums in the process of transferring citizens’ royalty to the Community. The ‘European consciousness’ is expected to be nurtured. However, what the European Union has done in creating ‘the European idea’ is that it supports and protects national architectural heritage by naming it as a regional heritage. This contradiction leads to a question what is the political reason behind these ambiguous activities? Certainly, the European Union’s efforts can be considered as a denationalization process, but it is rather a complex one. This opens up another question: how and why does architectural heritage function in the European Union’s process of denationalization?