On the Epistemological Interpretation of Parmenides DK B16

1

On the Epistemological Interpretation of Parmenides DK 28 B 16

(Aristotle,

Met.

IV 5, 1009 b 22-25 = DK 28 B 16; Teophrastus,

De sensibus

1-3

499.18-21 Diels ed.

Dox

. = DK 28 A 46)

Beatriz Bossi

(Universidad Complutense de Madrid)

I.

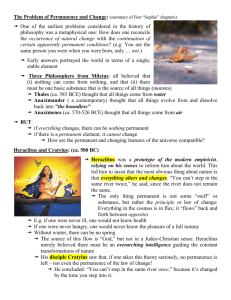

I would like to explore here one of Parmenides’ most controversial fragments, which includes important philological difficulties, and has been understood in contrary directions, and placed in different places: most scholars place it on the way of ‘deceitful opinion’ 1 while a few place it on the way of truth 2 . In the past, others seem to have made big efforts to reconcile vv. 1-2 with the rest of the fragment, as if it had two different parts 3 . Scholars have considered the ‘physiological’ ground of the fragment, from different perspectives: some seem to emphasize the intimate connection between the mind and the body as ‘crude materialism’ 4 while others make a positive description of this fact. Obviously, the fragment bears extreme readings, due to the presence of ‘deceptive words’, to put it in Mourelatos’ terms 5 . In my view, Aristotle might be partly responsible for such a wide spectrum of interpretations, as he seems to have used

Parmenides’ fragment to support his criticism against Protagoras’ relativism, by including him on his list of thinkers who, instead of distinguishing aísthesis from noésis ‘properly’ (as he did), considered the latter as a kind of ‘changing bodily alteration’ and gave rise to the (wrong) view that every ‘phenomenic’ sense-mental-perception is necessarily true.

In order to help us regard Aristotle’s remarks adequately, some interpreters have attempted to release us from the anachronical reading that attributes to Parmenides the much later opposition between ‘senseperception’ and ‘thinking’, (namely, our Platonic-Aristotelian glasses), so as to regard the fragment in a more archaic perspective, by emphasizing the fact that noeîn basically means, at his time, ‘general knowledge’ or ‘general cognition’ 6 . However, if this ‘general cognition’ meaning of noeîn were extended to all the instances of the term (and its family words), we could again fall into an extreme position that would deny Parmenides what, in my view, really belongs to him, namely, the distinction between ‘senseperception’ from ‘mental-perception’, though he uses the words without warning the reader about the

1 Gómez-Lobo (2006, 173-4).

2 Loenen places it in the Way of Truth (1959, 58-60) as well as Robinson (1989, 161, n. 8); Bollack is also inclined to see the fragment in a strong connection with F 4 (1957) and Mourelatos confesses that if

“the second sentence had been preserved in isolation, we would feel justified to place it in the context of

‘Truth’ ” (1970, 256).

3 Alexander thought that the words tò gàr autò éstin belonged to Aristotle, trying to articulate two different passages of Parmenides. This way Alexander makes a material parallelism between the quotation of Empedocles and Parmenides’ vv. 1-2 (see Cassin- Narcy, 1987, 284, n. 9). However, apart from the evident similarities between these two quotations, I suspect Alexander himself might have found vv 2-4 extremely difficult to reconcile with the former ones, and this, I claim, might be due to Aristotle’s misleading interpretation. von Fritz found an insoluble paradox: if noûs is a purely intellectual infallible capacity, it cannot be reconciled with the wandering nóos in F. 6.5-6; he found the explanation of the errors of nóos in F 16 vv 1-2, but he could not solve the problem of the internal logical construction of the fragment as a whole (1945, 237).

4 Gómez-Lobo (2006, 173-4).

5 Mourelatos (1970, 255-259).

6 Verdenius (1942); Kahn (1969); Calvo (1970); Robinson (1975 and 1989).

2 change of meaning. He certainly adumbrated the later Platonic ‘concept’ of noeîn by giving one of the features of this type of knowledge, as ‘cognition of what is not present’, according to F 4. In general terms, it can be agreed that neither Parmenides nor Plato were precise at using their most significative terms, according to Aristotle’s perspective and distinctions, (which we have made ours, though, again, we are not always aware of this fact). Curiously, Aristotle interprets Parmenides’ views in a more enlightening precise way in other passages 7 and he even might have been aware of this Parmenidean more restricted use of noeîn .

8 Again, in this respect, interpretations vary considerably: while some scholars feel friendly towards Aristotle’s separate treatment of the Parmenidean ‘physics’ from the Parmenidean

‘metaphysics’ 9 , pressumably due to Parmenides’ own emphatic clear distinction of the epistemological status of both ways, other scholars seem to suspect Aristotle’s treatment of F 16 is more manipulative than it should be 10 .

I will present Aristotle’s probable construction of the fragment, his contribution to our comprehension of the meaning of Parmenides’ fragment, and the extent of his criticism, which, in my view, shows a misunderstanding of Parmenides’ teaching. Secondly, I will consider Theophrastus’ philological clues, which allow a different construction and interpretation. Finally, I will explore the ontological implications of the fragment, and attempt to offer some light on the main difficulties that remain beyond the anachronical aspects of its historical setting, while trying to focus on a more Parmenidean perspective.

II.

According to Plato ( Theaetetus 152 e 2), the list of thinkers who made up Protagoras’ intellectual genealogy excluded Parmenides. However, Aristotle seems to include him, by appealing to four verses he quotes from memory, that happened to become fragment 16. This way, he makes a much more ‘radical’ claim 11 .

Ross 12 summarizes Aristotle’s argument as follows:

‘They <Protagoras’ antecesors> identify thought with sensation, and sensation with physical impression.

This view is found in Empedocles, Democritus, Parmenides, Anaxagoras and even (it is said) in Homer.

If the great masters are so skeptical about truth, the beginner may well dispair’.

7 Met. I 5, 986b 27-987 a 2: I will consider this passage below; De Cael. 298 b 14-24: Parmenides’ and

Melissus’ followers are not physikoi but investigate something different from and former to research in physics ( héteras kaì protéras physikês sképseos ) about which they speak properly ( légousi kalôs ); Alex.,

Aphr. in Metaph. 31.7 (28A7): Alexander attributes to Aristotle in the Physics the claim that Parmenides stepped on both ways ( ep’ amphotéras êlthe tàs hodoús ) and distinguishes them as kat’aletheain and katà dóxan which means that at this stage he was faithful to Parmenides’ own terms. He also says that

8 But instead of keeping the term as it comes in strong connection with tò eòn (as for instance in F 3), he seems to have replaced it by lógos , and by doing so, he might have misunderstood Parmenides’ teaching, by imposing his own categories upon him, as he does, in my view, in other places such as Phys. 184 b 25a 5; Simpl., in Phys. 115.11; De gen. et corr. 325 a 13-20.

9 Mansfeld’s concludes that in a certain way Aristotle and Theophrastus were right, in the sense that for the ‘ancient physiciens’ to perceive and to know were the effects of the variable constitution of our bodies and of the environment, which could be valued as a reductionism from a modern perspective (1999, 342-

4).

10 Cassin-Narcy (1987).

11 To say it in Cassin-Narcy’s terms (1987, 279).

12 Ross (1953, 273).

3

However, what Aristotle really says does not necessarily adequate to this description, for, instead of speaking of noeîn taken as ‘thought’ in his own Aristotelian technical terms, we could understand

Parmenides and Aristotle as refering to ‘knowledge’ in a more general vulgar way:

“And in general it is because they suppose that knowledge ( prónesin ) is sense-perception ( aísthesin ), and sense-perception, alteration ( allóiosis ), that they say that the phenomenon according to sense-perception

( tó phainómenon katà tèn aísthesin ) is necessarily true ( ex anánkes alethès ); for it is on these grounds that both Empedocles and Democritus and practically all the rest have become to claim such opinions as these.

Empedocles says that those who change their <bodily> condition change their knowledge ( phrónesin ):

‘according to that which is present to them, mind increases in men’

(DK 31 B 106)

In another passage he says:

‘as they change into a different nature, so it always comes to them to know differently’.

(DK 31 B 108).

And Parmenides too declares in the same way:

For as each one ( hékastos ) 13 has the mixture (échei krâsin ) 14 of the

flexible/much articulated 15 <bodily> limbs (meléon polukámpton) so understanding ( nóos ) 16 occurs/ comes to men <’s heads> ( parístatai ). For the same

( tò gàr autò ) that ( hóper ) knows ( phronéei ) is the constitution ( physis ) of the <bodily>limbs in each and every man. For what predominates <in men> is knowledge ( nóema )”

(DK B 16)

(Arist., Met . IV, 5. 1009 b 12-25)

It might seem striking that Aristotle attributes to Parmenides the identification of phrónesis with aísthesis 17 , and the description of these ‘phenomenal’ operations as necessarily true. On the one hand, in general terms, it can be agreed that in Parmenides’ time ‘the two had not been clearly distinguished’, and so it was impossible for these thinkers ‘to be definitely either rationalists or sensationalists’ 18 in a technical sense of these words, and so, one might infer that he could not have identified as the same, what he could not even distinguish accurately. On the other hand, it is also true that Parmenides at times seems to distinguish them as different types of knowledge: while in F 4, he seems to imply that noeîn has no

13 The ‘easy’ reading is hékastos (‘each one’) as subject of é chei krâsin : Arist. E 2; Alex.; DK; Albertelli;

Gadamer; Loenen; Bollack; Casertano; Robinson). Jaeger and Ross adopt the best testified reading: hekástot’ (‘at each moment’) Arist. E 1 J; Theophrastus: hekástote, as well as Diels, Calogero,

Verdenius, Fraenkel, Schwabl, Untersteiner, Mansfeld, Tarán, Ruggiu, Mourelatos.

14 Aristotle and Theophrastus: krásin . If hekátost’ is accepted, most scholars adopt Stephanus’ emmendation: krâsis (see Karsten, Calogero, Verdenius, Vlastos, Fraenkel, Tarán, Mourelatos, O’Brien).

15 The limbs can be interpreted as the organs of the body (cf. Il ., 5.214; 17.211; Od ., 6.140; 10.363;

18.219), or as the two forms that make the world. The human body is just a case among the components of the cosmos, for it turns out to be a mixture of the same forms Light and Night. Verdenius (1942, 6-7) interprets the union of male and female (F 12.4-5) symbolizing the origin of the world, as a mixture of

Light and Darkness, according to F 9.3. Analogously, Conche (1996, 244) observes that the mention of the mixture here evokes the goddess’ procedure to generate every entity by mixing Fire and Night (F. 8.

57-59), so that everything in the world is the result of that mixture, in variable proportions. The intimate

‘material’ connection between the cosmos and the constitution of the body is typical in pre-Socratic philosophy.

16 Nóos is translated as ‘mind’ by Tarán, Gallop, O’Brien, Casertano and Gómez-Lobo among others;

‘understanding’ gives an operative aspect, the same as ‘entendimiento’ (Bernabé) and ‘conocimiento’

(Eggers Lan) or ‘ascertainment’ (Robinson).

17 Aristotle claims that both noeîn and phroneîn were regarded as aísthesis by the early thinkers also in

De Anima III, 3, 427 a 17- b 7 where he refers to Empedocles, by quoting from memory the same two verses as here, and to Homer, without mentioning Parmenides, but perhaps implicitely including him by refering to ‘all of them’ ( pántes a 26). In De Anima I, 404 a 27-29 he refers to Democritus who identified psychè kaì noûs

.

18 Ross (1953, 275).

4 object present to the eye, in F 16 the physical connotation is evident 19 . And yet, one could wonder whether this connotation is really applicable to the fragment as a whole, or one should distinguish, inside the fragment, different types of knowledge.

Another difficulty is the attribution of infallibility to these gnoseological operations, which cannot be reconciled either with F 7 where Parmenides refers to an ‘aimless eye’ and ‘an echoing ear’ ( áskopon

ómma kaì echéessan akouén vv. 4-5) or with the famous lines where the goddess refers to ‘a mind that goes astray’ when she attributes a plaktòn nóon to mortals (F 6.5-6).

20

A few lines below Aristotle insists that these thinkers “supposed that the real <things> is confined to the sensible <things>’… ( Met. 1010 a 1-3: tà d’ ónta hupélabon eînai tà aisthetà

) (28 A 24). Again Ross summarizes this view by saying:

‘The ground of this opinion is the identification of reality with the sensible world, in which there is much of the indeterminate. These thinkers reflected that the sensible world is always changing, and that about the changing nothing true can be said’ 21 .

In Metaphysics I, 5 as well as in other places, Aristotle offers a more precise presentation of Parmenides, who, on the one hand, focuses on tò ón , while, on the other hand, offered explanations about becoming:

‘being compelled to accord with phenomena, and assuming that being is one in definition but many in sensation ( tò hèn mèn katà tòn lógon, pleío dè katà tèn aísthesin ) he posits in his turn two causes…’ 22

However, in the immediate context of our fragment Aristotle seems to reject the way of Truth completely.

Why is Aristotle supposed to take Parmenides’ view so partially when he is supposed to be aware of the whole Poem and knows that ‘the real’ is totally different from ‘the sensible changing multiplicity’ which is supposed to be the result of viewing tò eón split up under mere ‘names’ that mortals agreed upon (F 8.

38-41)?

In spite of Aristotle’s generalization, it could be argued that it is not clear whether Parmenides is really included among the philosophers that are critized, but could be mentioned only because he is supposed to

19 For a detailed analysis of this difference see Calvo (1977, 248-250). He asserts that nóos has two meanings: 1). a broad one as ‘cognition’ or ‘the principle of knowledge in general’ ( noeîn equivalent of gignóskein as in F. 2.7) that also appears in F 6.5 and in F 16. 1-2 ‘in which Parmenides emphasizes the influence of physiological factors upon knowldege’ supported by Theophrastus, and 2). a restricted sense as ‘representative cognition of what is not present’ in F4, and perhaps, he says, also in F 7.2 and F. 8.51.

20 The goddess holds the young boy back from two searching routes, first from the negative way which affirms non being, ‘… and then next from the <way> which mortals fabricate, knowing nothing, double-headed.

For helplessness guides in their hearts (a mind astray ( plaktòn nóon ), as they wander along ( pláttontai ), unhearing and no less unseeing at a time, hordes incapable of discernment, by whom the fact of being and not to be are reckoned as the same, -and not the same; of all <these people> the path is one and turns back upon itself. (F 6. 4-9).

21 Ross (1953, 273).

22 “Parmenides, however, seems to speak with rather more insight. For holding as he does that not being, as contrasted with being, is nothing, he necessarily supposes that being is one and there is nothing else

[…] but being compelled to accord with phenomena, and assuming that being is one in definition but many in sensation, he posits in his turn two causes, i.e. two first principles, hot and cold, or Fire and

Earth. Of these he ranks hot under being and cold under not being” ( Met.

I, 5. 986 b 27-987a 2 = 28 A 24 and 25). In De cael.

(298 b 14-24) Aristotle seems more precise as he claims that Parmenides’ and

Melissus’ followers rejected generation and corruption.

5 offer an explanation similar to Empedocles’ one with regard to the way the mind operates, i.e. depending on the state of the bodily mixture 23 .

However, one thing is a). to recognize a relation between the state of the body and its effects on the mind

(which Aristotle himself accepts in his holistic analysis of psychosomatic phenomena) and a different one is b). to reduce mental activity to its physiological conditions, and to make Parmenides identify

‘sense-perception’ with what could be called ‘mind-perception’ or ‘mental-perception’ 24 .

There are two possible alternatives at constructing vv.1-2: a) the easy reading ‘ hekástos and b) the more difficult but best testified reading hekástot’ (‘at each moment’). If this is the case, again one has two alternatives: b.1) to take nóos as the subject 25 (leaving krâsin

), and make Parmenides say that ‘according to the condition in which <the mind> has the body at each moment, it comes to men’, which would render Aristotle’s criticism absurd, for it would make the mind the owner of an instrumental body or b. 2) to adopt krâsis as subject to échei . I will go back to this option.

If we adopt either a) or b.2.) in vv.1-2 Parmenides seems to make a distinction between ‘the mixture of the limbs’ i.e. the condition of the body, on the other hand, and ‘the mind’ or the act of understanding, on the other hand. However, this distinction does not seem to be totally compatible with vv. 2-4, if

Parmenides were claiming the second thesis, as Aristotle’s criticism makes him say, namely that it is ‘the constitution of the limbs’ itself that ‘knows’ ( phronéei

). If the condition of the mixture of the ‘much articulated’ limbs that has an effect on the mind, is also ‘the same’ <faculty or principle> that knows,

Aristotle could deduce, from the fragment so constructed, ( hoper in nom. emphasizing the identity 26 ) that

‘sense-perception’ and ‘mind-perception’ are one and the same, according to Parmenides.

Interesting though it may be, let us note that in vv. 1-2 a strong causal link is established between two different levels, and that it is precisely the difference between the ‘bodily condition’ and the ‘mind’ or

‘the act of understanding’ what supports the link. Are we to suppose that this difference vanishes as we come to vv. 2-4? This step is not obvious.

23 For a comparative analysis of the correspondences between Empedocles’ and Parmenides’ quotations see Verdenius 1942, 7; 9; 20-4 and Cassin-Narcy 1987, 282-283.

24 Verdenius argues against Böhme that “If noeîn is taken to have the original meaning of ‘knowing’, the statement that in epic poetry noeîn ‘gradually’ could be ‘substituted’ by ideîn is not correct. Noeîn originally does not seem to have been connected with a particular organ. Both thumôi noeîn

( Od. 18, 228) and ophthalmoîs noeîn ( Il.

15, 422) occur’ though he agrees with Böhme’s general translation of the verb as ‘penetrating into the real nature of an appearance, perceiving that an object is a specific thing’. As opposite of sense-perception Verdenius claims it is not likely that this was the case with pre-Socratics, not even Xenophanes (p. 24). He observes that though in F 16 noeîn

keeps this wider meaning of ‘knowing’, the substantive nóos already occurs in a narrower, non-empirical sense in F 4 where it seems dissociated from the senses ( leûsse d’hómos apéonta nóoi paréonta bebaíos ). He concludes that it was hard to imagine a non-empirical faculty of knowing and that ‘originally it was thought of as a particular kind of perception’ (1942, 65-66). Since then, many other scholars, such as Kahn, Calvo and Robinson, among others, have added their own evidence to this view.

25 Diels considers that nóos in v. 2 is also the subject to échei . I think this interpretation leaves us with an

Aristotlelian projection on Parmenides and with a Platonic Aristotle who could claim that the mind (in the sense of the Agent Intellect) ‘has’ the body at its disposal to make men ‘think’. On the other hand, the problem is that it would be difficult to reconcile this claim with lines 2-4 where Aristotle seems to imply that the ‘nature of the <bodily> members’ is what knows. Coxon agrees with Diels’ construction (1986,

248).

26 Coxon claims this phrase is a regular identifying formula, in which the relative clause defines the reference of the pronoun, and offers examples to clarify this (1986, 249).

6

Parmenides does not make any explicit distinction between the first limbs (v. 1) and the second ones (v.

3) except for the presence of the adjective polukámpton (‘with many articulations’, flexible) -which

Theophrastus replaces by poluplánkton (‘much-wandering’)-, and the replacement of krásis (v. 1) by physis ‘constitution’ (v. 3) is not likely to denote a different a referent beyond the physiological level.

However, this does not annul the presence of nóos which could remain as an operative capacity beyond mere sense-perception. In my view, what Parmenides is suggesting in vv. 1-2 is that the mind, as the act of understanding and knowing, has a strong bodily dependence on the ‘much-wandering’ 27 limbs that make up the body. What might be happening in vv. 2-4 is that the ‘constitution’ of the limbs, which normally refers to the body as a whole, is now taken in its most relevant capacities. This seems to me a better way of understanding Parmenides’ terms, than merely making him reduce mental-perception to its sense-perception changing conditions.

It is interesting to note that in L.S.J. Lexicon , where the fragment is quoted as Aristotle transmits it

( parístatai instead of Theophrastus’ parésteken ) the translation chosen for this particular instance, among many other meanings of this common verb, is to ‘occur to one’, or ‘to come into one’s head ’. This meaning has the advantage of being free from metaphysical overtones, and so it turns out to be enlightening, for then, both, Parmenides’ claims and Aristotle’s criticism turn out to be more intelligible to us. The bodily condition has an effect on the mental act of understanding 28 , for it is the body in its very nature ( phúsis ) which performs these sense-mental operations ( phronéei ) in men, namely, the organs of sense-perception and the brains and the heart 29 . And this is so, because ‘what predominates <in men> is understanding’.

However, let us finish the analysis of Aristotle’s interpretation, by saying that there is enough evidence from other fragments of Parmenides’ Poem that it is neither true that ‘physical perception’ and ‘mental perception’ are to be identified as being the same, nor that any of them is infallible 30 , for most mortals not

27 Theophrastus is more likely to be presenting the right adjective than Aristotle who is probably as usual quoting from memory. Polukámpton ‘flexible/ much-articulated’ in Aristotle’s manuscripts is replaced by poluplánkton , transmitted by Theophrastus: ‘much wandering’ denotes the fluctuating condition of every body, probably due to the fact that their constituting mixture of Light and Night does not keep steady at any time. Besides the presence of pláttontai and planktòs nóos in F 6.5-6, Parmenides also refers to the mortals -who have set their minds on naming two forms- as peplaneménoi : ‘strayed’ from the truth ( F

8.54). See also Cordero’s notes on these words: they all connect to the verbs planáo and plázo with similar meanings: ‘to err’, ‘to go astray’, ‘to wander around hazardously’, ‘to miss the opportunity (2005,

180).

28 There could be something implicit in fragment F16 1-2 which is explicit in F 6.5: helplessness, incapacity, ( amechaníe ) guides in their heart ( stéthesin ) a mind astray ( planktòn nóon ). If this incapacity

‘in their hearts’ that guides their minds astray is fear of accepting Parmenides’thesis (before starting the way of opinion and conjecture properly), it might be taken as an explicit instance of this general influence or effect of the bodily condition (including pathe ) on the mind as it comes in F 16, and also it can be connected to this particular expression ( planktòn nóon ) that concisely captures, in my view, Aristotle’s wrong interpretation of Parmenides here.

29 It is said that Parmenides was a physician, and so he could have had some knowledge about the way the body functions, according to the medicine treateses at his time.

30 To say the opposite takes us straighforward to what Protagoras claimed. Plato might have figured out the danger of misunderstanding Parmenides by interpreting his claims from a Protagorian perspective and making the former, the refuge of any sophist denying false judgements. Aristotle denounces here the danger of postulating an ‘identity’ between sense-mental-perception and truth: if any statement is supposed to capture the real, the principle of non-contradiction is rejected and no science is possible (see

Cassin-Narcy 1987, 290). Otherwise if sense-mental-perception were understood as ‘mere apprehension’ in Aristotelian terms, he would not be critical, but would basically accept Parmenides’view.

7 only sense-perceive but also judge wrongly. To sum up, according to Aristotle’s relativistic

(anthropological) assumptions about this fragment, Parmenides stands on the same epistemological basis as the sophists, and the fragment turns out to be inconsistent with the main relevant claims declared by the goddess.

III.

With regard to Theophrastus’ version 31 , he seems to have had the manuscript in his hands, but the second sentence in the fragment is not paraphrased by him and therefore it is not clear how he understood it. His use of the perfect parésteken seems to be closer to Parmenides, for Aristotle might have ‘unconsciously assimilated the tense of Parmenides’ verb to that used by Empedocles, which he had just written’ and it is best understood in the light of Homer’s use of it 32 . Theophrastus introduces the first verses of F 16 by commenting that Parmenides did not say anything ‘definite’, but only that, due to the fact that there are two ‘elements’ ( stoicheíoin ), knowledge ( gnôsis ) 33 depends on the predominance ( huperbállon ) of one of them: our diánoia will become one way or the other according to the prevalence of the heat or the cold; better and purest will be the one according to the heat, though even this one requires some proportion

( summetría ). Then he seems to repeats Aristotle’s critical claim: tò gàr aisthánesthai kaì tò phroneîn hos tautó legei : ‘he regards to (sense) perceive and to know as if they were the same’. He adds that also recollection and oblivion are produced from the elements, because of the mixture ( tèn mnémen kaì tèn lèthen apò toúton gínesthai dià tês kráseos ). Finally he vagely refers that:

“Nevertheless, he attributes sense-perception also to the opposite itself, which is clear from the passage in which he affirms that a corpse does not perceive light, heat and sound because it lacks fire, but does perceive their contraries, cold and silence. And in general everything that is has some knowldege: kaì hólos dè pân tò ón échein tinà gnôsin ”.

Thus, Theophrastus sets the fragment in a more cosmological scenario, and 1) breaks the Aristotelian

‘necessity connection’ to truth, by admitting that, if the temperature, the purity and the proportion of the mixture are poor, so will be the quality of ‘knowledge’ ( gnôsis ). Let us note that first he uses this general world, but then he passes to a more specific one such as diánoia . The point is that if the mixture is in a bad condition (with regard to either temperature, purity or proportion) it can cause oblivion, i.e. it may make ‘knowledge’ disappear. On the other hand, 2) he seems to repeat Aristotle’s claim but in fact he could be just explaining what Parmenides said, without critical overtones: to sense-perceive is like

(emphasizing hos ) to know ( phroneîn as ‘to know in general) as well as to know is a kind of perception

(either sensitive or mental). Finally, 3) he does not seem to imply that ‘everything that is’ can

‘remember’, ‘imagine’ and ‘think’, in Aristotelian terms, but he appeals to a Parmenidean instance, namely, the way a corpse knows, which we would qualify as weak ‘sense-perception’ (as the soul of the person involved might be leaving the body?) to make Parmenides’ claim ‘ kaì hólos dè pân tò ón échein

31 De Sensibus, 3 499. 18-21 Diels ed. Dox.

(28 A 46).

32 Coxon (1986, 249). When parístatai (Aristotle, Alexander and Asclepious) is replaced by parésteken in perfect, according to Theophrastus’ parésteke , some translations are: ‘comes’ (Tarán; Mourelatos);

‘adviene’ (Eggers Lan); ‘is present’ (Gallop; Austin; Coxon); ‘se dotó’ (Bernabé). However, other scholars keep parístatai and translate: ‘si determina’ (Casertano), ‘depends on’ (Robinson) ‘viene in mente’ o ‘si presenta al pensiero’ (Calogero).

33 As he uses gnôsis when introducing this fragment, Calvo deduces that he seems to take F 16 as a general statement about knowledge and he is likely to undertsand nóos

, phroneîn and nóema

as including both sense-perception as well as mental-perception. (1977, 250).

8 tinà gnôsin ’ intelligible to us. Therefore, in my view, he shows a more didactic attitude, as he is attempting to expose and make Parmenides’ thought understandable.

Following these guidelines, and setting aside Aristotle’s implication of necessary true apprehensions

(either sense or mental), in the light of Parmenides’ Poem , F 16 has been interpreted 34 as providing the cause of the common erroneous apprehensions of the majority: they missapprehend the real because at each moment their minds follow the mixture of their ‘much wandering’ organs.

However, it is difficult to make the fragment as a whole consistent with other fragments of the Poem if one expects to explain the first sentence (vv. 1-2) by appealing to the second and the third ones. For, if

1). the constitution of the body is changeable, and it not only ‘affects’ the way the mind operates in men, and this is explained because

2). the body is in fact what knows in all and every men, and again, this is so, because

3) ‘what predominates is nóema ’ but now, (in the light of Theophrastus’ commentary), it is not necessary to interpret that tò plèon refers only to men, but should rather refer to ‘everything that is’, it will be necesssary to suppose that ‘what predominates’ is also wandering in itself.

However, if this is so, two new difficulties remain:

1). how are we to explain that the nature of the limbs, if it is supposed to be ‘changeable’ in itself,

‘knows’ something, when knowledge seems to imply having what is known ‘firmly’ present to the mind, according to F 4.1? and

2). if the wandering (erroneous) apprehension extends to all human beings, how is it possible that

Parmenides could escape from it and get to know the real?

IV.

It seems that some changes are to be made to the first translation, if we are to make sense of it from a more Parmenidean perspective. The main points are the construction of vv. 3-4 on hóper in accusative, as the object of phronéei

and the interpretation of tò plèon

as the full, rather that as ‘what predominates’.

This way F 16 can be translated as follows:

For as, at every moment, is the condition of the mixture in the wandering limbs, so understanding presents to men. For the same is what ( hóper ) the constitution of the limbs knows in all and every human being; for 35 the full is knowledge.

Though Aristotle probably constructed hóper in nominative 36 as subject of phronéei in order to attribute to Parmenides the identification of sense-perception and mental perception, it can be taken in accusative as the object of phronéei 37 . As a result, Parmenides is not saying that the nature of the limbs is ‘the same’

<faculty, principle> that sense-perceives and mentally perceives, but that it is what knows or apprehends

‘the same’ in all human beings. In my view this could make a remarkable difference. If the emphasis is

34 See von Fritz (1945, 237).

35 Denniston’s suggests (1966, 64-65) that the third conjunction does not introduce an explanation of the preceeding verses but both the second and the third ones give further explanations of the initial thesis

(vv. 1-2). O’Brien understands this indication as follows: There are two conditions that explain the corresponding changes that make knowledge: a. the perceived object must be the same for every human being, and b. the predominant < morphé > (F 8.53) is what constitutes thought.

36 See Burnet, Diels, Kranz, Coxon, Albertelli, Kirk-Raven, Austin, Beaufret, Cordero.

37 See Schwabl, Fraenkel, Hoelscher, Tarán, Mourelatos, Robinson and O’Brien among others.

9 placed on the claim that the nature of the limbs knows ‘the same’ in all human beings, something new is asserted about the object , namely, that what the bodily mixture captures ‘from’ the real and presents to

‘the mind’, so to speak, at each moment, i.e. with regard to every single object as such, is the same in all human beings. The link between the bodily perception and the mental perception (vv. 1-2) is explained further: when the ‘internal’ bodily organs know <something> it must be the same for everybody, a unity in itself, namely, something that can be recognized as such somehow: an identity. If everybody apprehends the same, then Parmenides could be understood, not as emphasizing the subjective relative changing side of sense-perception, in a Protagorean style, but as attending to a more ‘epistemic’ aspect of this kind of knowledge that the body provides. The perception of an identity in form is, to say it in

Aristotelian terms, a necessary condition of knowledge, not just for intellectual abstract concepts but also for what Parmenides might be adumbrating here in F 16, namely, that mysterious ‘lost link’ that takes the physical contact between sense-perception and the world -according to the ‘like by like’ principle- to a more ‘formal’ level of knowldege that requires ‘identity’ and does not necessarily require visual presence, according to F 4.

Moreover, it is the same ‘because’ tò pléon estì nóema .

Many scholars read tò pléon , as ‘what predominates’ 38 following Theophrastus, and as a reference of F 9.3: pân pléon estìn homoû pháeos kaì nuktòs aphántou

(‘all is full alike of light and of night invisible, both of them equal’). However, F 8.24-25 seems ‘an equally plausible candidate’: pân d’empleón estin eóntos (‘it is instead, all <of it> full of being’). If being is continuous, for ‘being keeps close to being’ then, there is nothing else left to know.

Scholars interpret tò pléon as plenum ‘the full’ 39 for different reasons. In my view, this last reading has the merit of keeping this fragment consistent with the way of Truth, while maintaining its logical internal links intelligible. With regard to the question of how to interpret the claim that ‘the constitution of the bodily limbs knows the same’ solutions are at variance. On the one hand, Vlastos 40 claims that it knows

‘becoming’, for the mortal structure cannot ‘think’ Being. Following Theophrastus, he asserts that the

‘predominance’ of Light only supplies the physical formula to know becoming. Knowldege of Being would rather demand the absolute dominance of Light, in order to have the ‘mystic’ experience of the immutable. Vlastos understands that both ways of knowing are kept as the two horns of a paradox that

Parmenides never solved and is impossible to solve, because it is the epistemological counterpart of his ontological dualism. Only the man guided by the goddess, while he perceives becoming, knows it is not real, and is able to ‘think’ Being 41 .

38 Vlastos, Kirk-Raven, O’Brien, Eggers Lan, Bernabé.

39 Tarán, Mourelatos, Robinson, Gallop, Austin, Casertano. Tarán (1965, 258-60) considers that if it is taken as ‘what predominates’, the phrase explains differences among individuals but not in the same individual. Different people think the same when Light and Night have a certain proportion in their respective bodies.

40 Vlastos (1946, 71-72). Verdenius (1942, 12-13) had considered that the man who knows, i.e.

Parmenides himself, is also included in the totality of men who are provided with this unsteady constitution, but we are to suppose that in his everlasting wandering an element of stability is hidden which directs his mixture so that Light prevails, ‘enabling him to conduct his wandering mind along the straight road of reasoning’. To this interpretation, Vlastos objects that the knowldege of Being would require not the ‘preminence’ of Light but full Light without a shadow of Night.

41 Vlastos (1946, 77).

10

On the contrary, according to other scholars, Parmenides claims epistemological rather than ontological dualism, for what is described in both ways is a different knowledge of the same reality- the universe 42 .

Therefore, an alternative to Vlastos’ perspective is to suppose that the nature of the limbs knows ‘what is’ 43 . However, interpretations vary. Bollack 44 understands that ‘to think’ and ‘the object thought’ are one and the same, because the nature of the limbs ‘in’ and ‘out’ of ourselves is the same.

After offering us an extremely interesting net of connotations of the most important terms of the fragment that give opposite clues (and so are likely to mislead the contemporary reader), Mourelatos 45 summarizes his position by saying that the fragment:

“…does three things: Openly and directly it gives a physiology of thought; indirectly it censures human thought as ‘wandering’ and ‘confusion’; but it also gives subtle reminders of the proper relationships between mind and reality” 46 .

He observes that in the light of B 8. 34 ff, one could be tempted to take physis as ‘inner essence’, phronéein as a global term combining ‘intellect, volition and affect’, and the last sentence tò gàr pléon estì noéma (appealing to a series of associations) as ‘thought is that which is realized’. In spite of the similarities he finds between F 16 and 3, 4, and 8.34 he does not want to ‘go too far in this direction’ for:

“The similarities can seduce us into treating the epistemology and metaphysics of ‘Doxa’ as the next best thing to the epistemology and metaphysics of ‘Truth’”- against Parmenides’ express warning to the contrary”. 47

However, following Mourelatos’ suggestion, Robinson 48 takes voós as ‘an example of a success-word denoting failure’ for he thinks that unless the goddess reveals the secret to mortals, they will never actually get to know the real. This observation reminds Vlastos’conclusion. But Robinson considers unlike Vlastos- that the unique and real referent of the various esti- ascertions is tò eón , to which all names in their imperfect own way keep pointing, though mortals cannot be expected to be aware of it. In

42 Finkelberg (1986, 405).

43 Robinson, Gallop, Ruggiu, Aubenque, among others. Aubenque observes that the three phrases that affirm the identity of thinking and being begin in the same way, introduced by tò autò : F 3; F 8.34 and

16. 2 (1987, 117 n. 48).

44 Bollack (1957) 68- 69: his thesis is that our limbs ‘think’ about limbs: the universe thinks of itself in the thinking of all men, and thinking is about ‘one thing’ which is ‘continuous and full’.

45 Among the negative connotations: when Parmenides writes tò gàr pléon estì nóema he is exploting the familiarity of the view that pléon is ambiguous and cannot be isolated from ‘the more relatively to the less’; the term is likely to derive from a vulgar usage, rather than from a philosophical one, (as when in

English one says ‘I’d rather’). Other implicit associations the author points out are: the ‘wandering mind’ is linked to the motif of the journey and the weary ‘limbs’ of the luckless traveler Odysseus ( Od.

17.511); the idiom parístasthai , (which I have mentioned above to associate it to ‘the heart’ or ‘the head’), views

‘thought’ as a completely ‘passive’ process (also Vlastos: ‘corpse-like passivity of sense perception’ quoted by M 255 n. 87) and so it is the ‘converse of a directed search’ and, more specifically, of ésti noeîn

: is there to know; in addition to ‘thought’ as pláne

, now krâsis

reminds the reader of ‘confusion’.

Among the positive ‘seductive’ ones: if tò autò is taken as ‘the same thing ’ (Tarán 258) how “can we resist the implication that this ‘same thing’ is tò eón ?” (M 256). M does resist: the correct implication is

‘condition’ or ‘state’. But he admits that ‘there remains an uncanny similarity both in wording and in syntax between B 16 and such lines as B3, B4, and B 8.34 (1970, 255-259).

46 Ibid. 257.

47 Ibid. 256-7 He translates F 16: ‘For such as is the state of mixture at each moment of the muchwandering limbs, even such thoughts occur to men. For it is the same [condition ] that the nature of the limbs apprehends among men, both all and each. For thought is ‘the full’ [and the more and the rather]

48 Robinson (1975, 631-2).

11 a similar approach Gallop 49 comments that if, in the light of F 8. 24, ‘all is full ( empléon ) of being’, this is the only content of thought, and therefore what the constitution of the body ‘knows’ in all men is ‘what is’. This reading is adumbrated in F 3: ‘for there is the same <thing> for being thought and for being’. I think this approach fits my

However, Conche 50 objects that this approach is impossible to maintain for it cannot explain either how mortals come to so ‘variable’ conclusions, if all know the same, or for what purpose the goddess’ revelation should be necessary.

I agree with Pérez de Tudela 51 that the immutable identity of the object of knowledge and the range of differences at apprehending aspects are compatible in Parmenides, for the same double perspective presents the Poem , taken as a whole. At this stage of the analysis, one has the impression that this controversial obscure fragment looks like a micropoem exhibiting the same big difficulties of the Poem in a nutshell.

It could be claimed that as both the world and the body are wandering mixtures most men only know multiplicities empirically, and ignore tò eón as if that knowledge depended on a mystic revelation from the goddess. One could be tempted to split the difficulties as Plato did: men’s bodies as well as physical bodies in general operate in a changing world, exchanging mixtures, exhibiting variation, while identity and permanence are grounded on a mystical knowledge only the goddess can supply 52 .

As the first sentence affirms variety: 1. change from the body to change on the mind, one expects the second one to do the same, if it is somehow explaining the former, but it goes the opposite way: 2. all men know the same. Why? 3. Because the full is knowledge. Does the third sentence go back to change or does it remain on permanence? The most obvious answer to me is that it should remain on permanence.

In other words, it does not follow, according to this Parmenidean logic, that knowledge is full of change, but that ‘the full is knowledge’.

In the light of F 9 one could say that if everything is a proportioned mixture of the same Forms, every man, at knowing, grasps the same. Most do not know so, but Parmenides does. However, the difficulty is that the postulation of the two Forms does not seem to be independent from the act of naming. If this is so, it seems that the fragment belongs to Doxa, to the perspective of the many, as part of the many conjectures men make (either plain people or famous philosophers). Morover, the Forms oppose themselves. Theophrastus claims one is purer than the other. All his distinctions in degree, quantity, temperature, do not lead us to the thesis of Parmenides but sound allien to it.

If the mixture is relative to human incapacity to accept Parmenides’ thesis, even when they think they understand and make progress by making ex-change, while naming, they really refuse his thesis at taking the part for the totality, every time ( hekástote ) they interpret whatever happens to come to either their senses or their mind.

49 Gallop 1984, 87.

50 Conche 1996, 248-251.

51 However, at the end of his commentary he does not seem to release Parmenides from Aristotle’s authority (see Bernabé, ed. 2007, 223-5).

52 Nestle (quoted by Verdenius 1942, 9) distinguishes empirical knowledge common to all men ( nóos

) from philosophical knowldege that only Parménides has ( nóema ) .

12

And yet one knows, Parmenides has revealed us, that the only alternative is to be. And one cannot resist the temptation to think that behind the wording of this fragment, Parmenides is still saying so, in a last subtle attempt to be heard 53

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertelli, P., 1939: Gli Eleati, Testimonianze e frammenti , Bari.

Aubenque, P., 1987: “Syntaxe et sémantique de l’être” en Études sur Parménide , Tome II, Paris, p. 102-

135.

Austin, S., 1986: Parmenides, Being, Bounds and Logic, New Haven and London.

Bernabé, A., (ed. y trad.), Pérez de Tudela, J. (comentario), Cordero, N. (epílogo), 2007: Parménides,

Poema, fragmentos y tradición textual, Madrid.

Bollack, J., 1957: “Sur deux fragments de Parménide (4 et 16)” Revue des études grecques 70, p. 56-71.

Calogero, G., 1932: Studi sull’ eleatismo, Roma.

Calvo, T., 1977: “Truth and Doxa in Parmenides” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie , 59, 3 : 245-260.

Casertano, G., 1989:

Parmenide, il metodo, la scienza, l’esperienza,

Napoli.

Cassin, B. y Narcy. M., 1987: “Parménide Sophiste, la citation aristotélicienne du fr. XVI”, en P.

Aubenque (ed.) Études sur Parménide , Tome II, Paris, p. 277-293.

Clark, R. J., 1969. “Parmenides and sense-perception.” Revue des études grecques , 82: 14-32.

Conche, M., 1996: Parménide, Le Poème: Fragments, Paris.

Cordero, N., 2005: Siendo, se es. La tesis de Parménides, Buenos Aires.

Coxon, A.H., 1986: The Fragments of Parmenides, Assen.

Curd, P., 1998: The Legacy of Parmenides, Princeton.

Denniston, J.D., The Greek Particles , Oxford.

Diels, H., 1897: Parmenide s Lehrgedicht , Berlín.

Eggers Lan, C., 1978: Los filósofos presocráticos, I, Madrid.

Finkelberg, A., 1986. “'Like by like’ and two reflections of reality in Parmenides.” Hermes , 114: 405-12.

Fraenkel, H., 1955: Wege und Formen frühgriechischen Denkens , Munich.

Fritz, von K., 1945: “ Nóûs,Noeîn and their Derivatives in Pre-Socratic Philosophy (excluding

Anaxagoras): Part I ”, Classical Philology 40, 223-242.

Gallop, D., 1984: Parmenides of Elea, Fragments, A text and translation with an

Introduction, Toronto.

García Calvo, A., 1992: Lecturas Presocráticas, Zamora.

Gómez-Lobo, A., 2006: El poema de Parménides, Santiago de Chile.

Guthrie, W. K. C., 1993: Historia de la Filosofía Griega, VI, Madrid.

Hershbell, J.P., 1970: “Parmenides’Way of Truth and B16”, Apeiron 4, p. 1-23.

Hussey, E., 1990. “The beginnings of epistemology: from Homer to Philolaus” in S. Everson (ed.),

Epistemology . Companions to Ancient Thought: 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): 11-38.

Jaeger, W., 1957: Aristotelis Metaphysica , Oxford.

Kahn, C.H., 1969: “The Thesis of Parmenides”, The Review of Metaphysics, 22.

Karsten, S., 1835: Philosophorum graecorum veterum praesertim que nte Platonem

floruerunt operum reliquiae. Vol. I: Parmenidis , Amsterdam.

Kirk,G.S., Raven, J.E., Schofield, M, 1999:

Los filósofos presocráticos,

Madrid.

Laks, A., 1988: “Parménide dans Théophraste, De sensibus 3-4.” La Parola del Passato , 43: 262-80.

Loenen, J.H.M., 1959: Parmenides, Melissus, Gorgias: A Reinterpretation of Eleatic Philosophy, Assen.

Mansfeld, J., 1999: “Parménide et Héraclite avaient-ils une théorie de la perception?” Phronesis , 44: 326-

46.

Mourelatos, A., 1970: The Route of Parmenides, New Haven and London.

53 The fact that it remains double and resistant to classification into either ‘Doxa’ or ‘Truth’ might be another symptom of its peculiar rich status, and a source for further reflection about human/divine reality.

13

O’Brien, D., et Frère, J., 1987: Le Poème de Parménide, Paris.

Reale, G., (trad.), Ruggiu, L. (commentario), 1991: Parmenide, Poema sulla Natura, Milán.

Reinhardt, K., 1916: Parmenides und die Geschichte der griechischen Philosophie, Bonn.

Robinson, T.M., 1975: “Parmenides on Ascertainment of the Real”, Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 4, p. 623-633.

1989: “Parmenides and Heraclitus on what can be known”, Revue de Philosophie

Ancienne, VII, 2, pp.157-167.

Ross, W.D., 1953: Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Oxford.

Tarán, L., 1975:

Parmenides, Princeton.

Vlastos, G., 1946: “Parmenides’Theory of Knowledge”, Transactions of the American Philological

Association 77, p. 66-77.

Verdenius, W.J., 1942: Parmenides. Some comments on his poem, Amsterdam.

Woodbury, L., 1986. “Parmenides on naming by mortal men: fr. B8.53-56.”

Ancient Philosophy , 6: 1-11.