Rachael Voyles - University of Colorado Boulder

advertisement

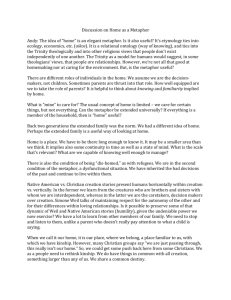

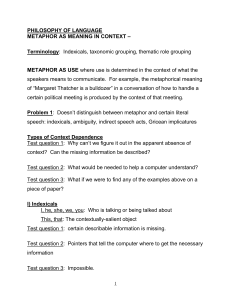

Voyles 1 Rachael Voyles Philosophy 216 Dr. Barnett 25 November 2002 Metaphor Metaphor is one of the challenges philosophers of language must overcome in their theories: how is an utterance which means one thing literally understood by both the speaker and the hearer to mean something else, and furthermore, how has this secondary meaning come to be the common meaning for many of these utterances we call metaphors? To examine these questions, this paper will first elaborate on what metaphor is and the extent to which it has infiltrated the English language. The way in which metaphor fits into Grice’s general account of linguistic meaning will be analyzed in order to produce a logical account of how metaphorical meaning is conveyed. For the purpose of simplifying this argument, a common, single-phrase metaphorical utterance will be discussed, yet the points made in this paper may be applied to elaborate, multi-sentence metaphorical concepts. Metaphor Metaphor falls into the category of figurative speech, or what John Haiman terms “unplain speaking.” A figurative or “un-plain” utterance communicates meaning other than the literal meaning of the utterance. For example, ‘Bob is a pig’ is a metaphor because 1) Bob, for the purposes of this paper, is a human and therefore not a pig, yet 2) the hearer of the utterance understands it to be relevant and meaningful, in this case to convey that Bob eats a lot. A property of pigs is re-attributed to something else, namely Bob. However, this reattribution of properties does not distance or detach the speaker of the metaphor from the meaning he or she is Voyles 2 communicating, the “actual referential content” of the utterance. It is this characteristic of metaphor that separates it from other linguistic strategies that are also in the category of “unplain speaking” such as sarcasm, hyperbole, and politeness (Haiman 10). The English language presents four types of metaphor: 1. Single-use metaphor, such as that found in poetry, is metaphor the hearer/reader encounters in a single situation (i.e. reading that poem). 2. Common metaphor is that which the average English speaker is familiar with such as ‘(name) is a pig’ discussed above. The familiarity suggests a certain reattribution of properties, but the hearer checks to see if this attribution fits within the context. 3. Those metaphors whose metaphorical meanings seem to have transgressed the literal meanings of the utterances so that the average English speaker automatically understands the metaphorical meaning of the utterance without considering context. 4. Ambiguous metaphor, which is between the common metaphor and type 3 so that the literal and metaphorical meanings are closely related. In this case, it seems that the hearer notes the literal meaning briefly while assuming the metaphorical meaning to be the intended meaning. Considering these four types, it becomes apparent that metaphor greatly influences the language. Metaphors can yield metaphorical concepts. For instance, the metaphor ‘Argument is war’ has come to produce common utterances such as ‘ He attacked the weak point of the argument’ and ‘She defended her claim,’ where “attacked” and “defended” are derived from the concept of war (Johnson and Lakoff 4). Another such example would be ‘Time is money;’ in turn, it is common to refer to time as valuable, and furthermore, for us to literally treat it that way. To identify metaphor, one must be able to distinguish literal meaning from metaphorical meaning. This is a debate between semantics and pragmatics. On the basis of semantics, the meaning of an utterance comes strictly from the conventional meanings and rules of the words Voyles 3 that form the utterance: literal meaning. Pragmatics, however, examines how the context the utterance occurs in shapes the meaning of the utterance; this allows for the possibility of metaphorical meaning. So, the question is, do metaphors still have a literal meaning in addition to their metaphorical meaning, or simply the latter? Grice’s analysis of linguistic meaning as related to metaphor Grice’s theory is based on the concept that language can be reduced to psychological terms. He believes that language is a “co-operative” process: there exists a relationship between intention, specifically that of the speaker, and meaning (Chapman 131). Out of this belief arises Grice’s Prolegomena, the idea that there needs to be a theory of pragmatics to explain how context combines with semantics to produce what is communicated. In an attempt to answer the prolegomena, Grice presents his account of linguistic meaning in terms of non-natural meaning. According to the account, someone Y means something non-naturally by X if and only if Y intends X to produce some effect in audience A by means of their recognition of this intention. Thus, metaphor communicates non-natural meaning and should fit into Grice’s account of linguistic meaning as follows: Speaker S means something linguistically by utterance U if and only if… 1. S intends to produce some effect in audience A by U. 2. S intends to produce the effect by A’s recognition of S’s intention to produce the effect. Within the above theory, Grice considers metaphor to be a case of “flouting the maxims” (Chapman 131). This phrase is in reference to a series of maxims Grice has outlined for communication. The maxim of quantity states that, in communication, the speaker provides only enough information necessary to convey his or her point. This maxim stipulates that the Voyles 4 information be relevant to the communication at hand. The second maxim is that of quality, which states that the speaker does not mislead the audience by giving false information. These maxims are “flouted” by metaphor because upon examination of the literal meaning of the utterance, it appears that the maxims are violated: this is additional information that is misleading to the hearer. However, only upon the audience’s belief that the maxims are met will the audience search for the utterance’s metaphorical meaning. According to Grice, when a speaker utters a metaphor, based on the literal meaning of the utterance, the speaker appears to be uncooperative; he or she is not making sense based on the conventional use of the words in the utterance. The hearer, however, assumes the speaker is cooperative and proceeds to interpret the utterance by searching for its metaphorical meaning. It is the context that suggests to the audience that the maxims are met and the speaker is cooperative. The metaphorical meaning of the utterance is then identified on the assumption of conversational implicature, or how what is communicated by the utterance differs from its literal meaning. The audience has considered the literal meaning of the utterance and examined the semantics to see if any rules are violated. Semantic rules were violated because the meaning from the conventional use of the words does not make sense in the given context and so the audience searches for another proposition expressed by the utterance. This reanalysis of the utterance by the hearer based on the above assumptions gives the utterance significance and the possibility of being true. This is, however, a learned process. Children must have metaphor explained to them until they can train their minds to go through it. Grice’s Prolegomena is greatly supported by metaphor. As seen in the process for finding metaphorical meaning outlined above, the combination of semantics and context leads to the conclusion that an utterance is a metaphor. Semantic evaluation rules out the literal meaning Voyles 5 of the utterance as the speaker’s intended meaning. The context speaks to the cooperativeness of the speaker. Additionally, when the audience searches for the metaphorical meaning the speaker is trying to communicate by the utterance, the audience uses the context to choose which reattribution of properties would make sense in the context. The fact that the literal meaning of the utterance is considered as part of the process to find the metaphorical meaning, suggests that a metaphor still has both literal and metaphorical meaning. Resulting analysis of metaphor (see Appendix A for derivation explanation) S intends to communicate metaphorical meaning to audience, A, by utterance, U, if and only if… 1. S intends to produce an effect in A by uttering U in context, C, such that A recognizes the maxims of quantity and quality as satisfied. 2. S intends that A conclude, based on A’s recognition that the maxims are satisfied, that S is a cooperative speaker (U is relevant and not misleading) in C. 3. S intends that A recognize that the maxims would be broken if U were being used literally. 4. S intends that A conclude, based on (3), that S intends U to be a metaphor when uttered in C. 5. S intends, with the recognition of A that U is a metaphor, that A search for meaning other than the literal meaning of U. 6. S intends that A will search C and A’s past experience in order to find this other meaning. Metaphors may or may not be represented as logical truths Consider the following example: Utterance: ‘Bob is a pig’ Voyles 6 Analysis 1: Bob is a pig. Pigs eat a lot. Therefore, Bob eats a lot. Analysis 2: Bob is a pig. Pigs are pink. Therefore, Bob is pink. Both analyses appear to be logically valid, yet only analysis 1 appears to be logically sound. This discrepancy exemplifies the different types of metaphor: single-instance, common, ambiguous, and that for which the metaphorical meaning has transgressed the literal meaning. ‘Bob is a pig’ is a common metaphor, thus analysis 1 is the first interpretation that occurs to the average English speaker when he or she searches his or her past experience along with the context the utterance is presented in (condition 6). If, however, this same utterance was a singleuse utterance—the hearer had not heard this metaphor before—it can be argued that the same English speaker would initially think both analyses sound. In a case of a single-instance metaphor, the hearer does not have past experience to relate to. The hearer thinks of the many attributes that the speaker may be intending to re-attribute, in this case the many attributes of a pig the speaker could be intending to re-attribute to Bob. It is the pragmatic side of the analysis that accounts for the selection of which property re-attribution or which analysis is correct and thus sound. Returning to the example, the hearer will understand from the context that Bob is a human and rule out analysis 2 since humans are not pink, coming to the conclusion that indeed only analysis 1 is sound. With the common metaphor, the process is simply expedited by knowing the common property re-attributed by the metaphor ‘Bob is a pig’ is that of eating a lot. The hearer then identifies whether or not this meaning fits into the context. If it does not, the metaphor will be treated as the single-instance metaphor and all the possible properties will be considered. Progressing up to the metaphor whose metaphorical meaning has transgressed the literal, the same basic process can still occur. Yet, the property re-attribution is so common that the average speaker unknowingly mentally Voyles 7 skips the procedure after searching his or her experience; the process is expedited to the greatest extent. It is evident by this pattern, however, that metaphor can be logically represented with the understanding that logical soundness is context dependant. Conclusion Metaphor conforms to Grice’s analysis of meaning on the basis of the relationship between speaker intention and hearer recognition of that intention. The systematic account of metaphor conforming to Grice’s account of linguistic meaning requires metaphor to have both literal and metaphorical meaning. The analysis highlights the systematic nature of metaphor; there is a pattern that people learn to allow them to try and make sense of utterances that they believe, based on the context, were uttered to convey relevant meaning. If this meaning is not gained by the conventional meaning of the words in the context, we seek metaphorical meaning by re-attributing properties of one thing to another. This process, within context, can be logically represented. Voyles 8 Appendix A Grice’s basic linguistic meaning analysis metaphorical meaning Speaker S means linguistically something by utterance U if and only if… 1. S intends to produce some effect in audience A by U Effect: A recognizes that U is a metaphor and therefore understands and accepts the metaphorical meaning of U as the meaning communicated by S through U 2. S intends to produce the effect by A’s recognition of S’s intention to produce the effect Intention: that 1) A recognize S’s intention for U to be identified by A as a metaphor and 2) A recognize S’s intention to communicate the metaphorical meaning of U (rather than the literal meaning of U) Further considerations Within this, S must select U such that A will be able to recognize that U is a metaphor. For this to happen, S selects U such that S believes A will recognize the maxims of quantity and quality are satisfied, that is U is relevant and is not misleading A by giving false information, respectively (in other words, S is understood by A to be acting as a cooperative speaker) And, S must select U such that the correct metaphorical meaning of U is conveyed to A For this to happen, S selects U such that S believes A will recognize the metaphorical meaning intended by S based on A’s past experience with metaphor combined with context C (where the maxims are met), in which U is uttered (Therefore, pragmatics is vital to an analysis of metaphor.) Voyles 9 Works Cited Chapman, Siobhan. Philosophy for Linguists: An Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2000. Haiman, John. Talk is Cheap: Sarcasm, Alienation, and the Evolution of Language. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. Johnson, Mark and George Lakoff. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980.