How to Naturalize Epistemology

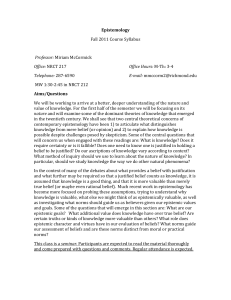

advertisement